Until now, the statistics on air pollution deaths have been presented in black and white – numbers on a page that estimate between 28,000 and 36,000 people will die as a result of toxic air pollution every year in the UK.

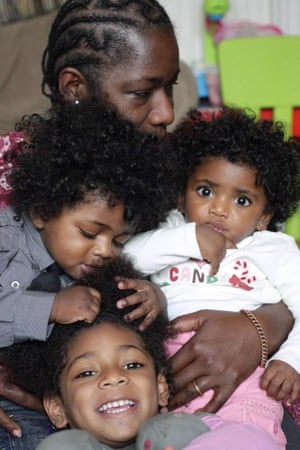

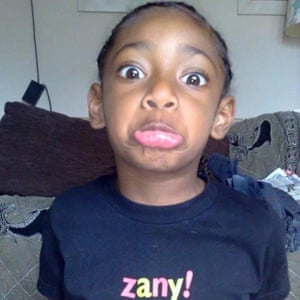

But the life and death of nine-year-old Ella Kissi-Debrah is in full colour: from the pictures of her wearing her gymnastics leotard hung with medals, to the image of her mother and siblings holding aloft her photograph, when they no longer had her to hold on to, as they campaigned for the truth.

As Prof Sir Stephen Holgate told the coroner, behind the often-quoted statistics lie individuals whose lives have been cut short. “Every single number that goes into these studies is a single person dying,” he said.

Holgate paid tribute to the resilience of Ella’s mother, Rosamund Kissi-Debrah, for her tenacity, which on Wednesday helped to make legal history when for the first time air pollution was recorded as a cause in an individual death in the UK.

The last two years of Ella’s life were punctuated by severe asthma attacks that led to her collapse and admission to hospital almost 30 times. Her lungs collapsed, or partially collapsed, on five occasions, as she struggled to survive what the coroner heard was a form of asthma that flooded her lungs with fluid.

It was Holgate’s examination of these years, recorded in medical notes from a range of experts whom Kissi-Debrah turned to for help, that led to a pattern emerging.

Unlike most people with asthma, Ella’s attacks were not triggered by pollen or respiratory infections but something else. Holgate’s work exposed that pattern as a seasonal one: it was in winter when air pollution levels spiked that Ella was brought down with coughing fits, which triggered secretions in her lungs that in turn triggered her collapses.

Ella and her family lived just 25 metres from South Circular Road in Lewisham, south-east London, where levels of nitrogen dioxide air pollution from traffic constantly exceeded the annual legal limit of 40ug/m3 between 2006 and 2010.

The scale of the crisis was a public health emergency, the hearing was told, and the efforts of the authorities to tackle it were glacial.

But as she walked to school along the main road and sometimes the back streets, Ella and her mother were in ignorance of the damage the toxic air was causing. No one had told them.

Kissi-Debrah said she knew almost nothing about air pollution or nitrogen dioxide while her daughter was alive. “I knew about car fumes, the phrase, but nothing else.”

The first inquest into her daughter’s death in 2014 recorded that Ella had died in Februrary 2013 of acute respiratory failure. There was no mention of any environmental factors causing the fatal collapse.

It was only when Kissi-Debrah launched a charity in her daughter’s name to improve the lives of children with asthma in south-east London that she started to make connections.

“I got a call from someone who told me [that] in the two days around Ella’s death there were big spikes in air pollution locally,” Kissi-Debrah said. From there the evidence grew, and the case was taken up by the human rights lawyer Jocelyn Cockburn.

When Holgate produced a report for the family last year linking air pollution levels to Ella’s death, the attorney general quashed the first inquest.

Over the past two weeks a very different inquiry into what took the nine-year-old’s life has been played out in the coroner’s court.

This time government departments, officials from the local authority and the mayor of London were questioned about what they did – or did not do – to reduce illegal air pollution levels around the area Ella lived.

Crucially, they were interrogated about whether they informed the public of the risk to their lives from the air they were breathing, and whether their failings might have breached Ella’s right to life.

In heartrending evidence, Kissi-Debrah, a former teacher, told the coroner that had she known the air her daughter was breathing was killing her, she would have moved house immediately.

“We were desperate for anything to help her. I would have moved straight away, I would have found another hospital for her and moved. I cannot say it enough. I was desperate, she was desperate,” she said.

The impact of leaving the toxic surroundings could have led to a different outcome for Ella, Holgate told the hearing.

He referred to a case in France last year, where a mother successfully sued the French state over the impact of living near Paris’s traffic-choked ringroad in Saint-Ouen. The mother and daughter moved to Orleans on doctors’ advice and their health improved considerably.

For Ella, that did not happen. But the finding this week by a London coroner that air pollution was to blame for her death, after her mother’s long fight for the truth may help to prevent other children in her daughter’s situation from suffering as she did.