1. Lucky’s by Andrew Pippos

Picador

This novel is a saga in the truest definition of that word, spanning more than 50 years of one Greek-Australian family and the rise and fall of their cafe franchise.

The story of Lucky’s follows various twists and turns of fortune and highlights the role of luck and serendipity in fate – almost like a Greek saga. Pippos skilfully weaves multiple story threads throughout the novel – the literary fraudster; the plucky journalist; the entrepreneurial Greek man who escapes service by impersonating a famous musician – but the most memorable parts of this book are the beautifully drawn characters and its warm heart. – Brigid Delaney

o Lucky’s by Andrew Pippos review – a must-read saga, and a gripping monument to Greek diaspora

2. Fathoms: The World in the Whale by Rebecca Giggs

Scribe

In 2013 an entire flat-packed greenhouse – hoses, ropes, flowerpots, glass – found its way into the belly of a sperm whale. “We struggle to understand the sprawl of our impact, but there it is,” writes Rebecca Giggs, “pollution, climate, animal welfare, wildness, commerce, the future, and the past. Inside the whale, the world.”

As we grapple with our Anthropocene anguish, some of the most alive, inventive writing on the planet is nature writing, and Giggs’ Fathoms is glorious proof. Ostentatious, mythic and strange, this is the kind of book that swallows you whole. Entirely fitting for its subject. – Beejay Silcox

o Rebecca Giggs: After everything this year, what we hear when we listen to birdsong has changed

3. A Room Made of Leaves by Kate Grenville

Text

Men wrote the early Australian colonial history. Women featured as bystanders at best. And so it was with Elizabeth Macarthur, wife of John Macarthur – colonial officer, inveterate political plotter who was seminal in the 1808 Rum rebellion and later credited with founding the Australian wool industry.

Kate Grenville conjures Elizabeth through a candid memoir that “came into my hands”. We meet Elizabeth, the imagined lover of the astronomer William Dawes. Elizabeth, who did more than John to establish the wool industry. And who realised history in the making was silencing the dispossessed local custodians too. – Paul Daley

o A Room Made of Leaves by Kate Grenville review – the untold story of an unruly woman

4. Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason

HarperCollins

Book jacket comparisons can be the death of a good novel (stop it with the “for fans of Sally Rooney” already), but in the case of Sorrow and Bliss, the Fleabag nod on its cover is fair. Meg Mason’s first novel is narrated by the acerbic, observant and deceptively self-aware Martha, an anti-hero with a witty quip for everything – and a partner, Patrick, who has banter to match.

That’s why I thought I’d picked up a perfect holiday read when I took it to a beach getaway earlier this year. But as the novel unfolded, whipping back and forth in time as we fill in the gaps of what Martha isn’t telling us, the sorrow of this story – and of the character’s hidden illness – leaks out all over it. I started this book reading out the funniest lines to anyone who would listen. I ended it in tears, with a lingering grief for its characters that I still haven’t quite been able to shake off. – Steph Harmon

o Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason review – an incredibly funny and devastating debut

5. Ghost Species by James Bradley

Penguin Random House

The climate crisis has shaped James Bradley’s fiction and nonfiction for years. In his latest novel, Ghost Species, that concern takes a slightly unexpected direction: the humanitarian consequences of a corporation’s attempts to revive ancient, extinct species to somehow re-engineer the planet.

Kate is wary when the Elon Musk-style entrepreneur and billionaire Davis Hucken enlists her to help him resurrect Neanderthals. Her ethical misgivings overwhelm her when the highly secretive project is successful and a baby is born, and she kidnaps the not-quite human child to raise her as her own. It’s here that the not-so-speculative frame of Bradley’s novel falls away to become a story of grief and love and the nature of family – and also not quite that, as the question at the heart of the novel continually rears its head: how ought we relate to nonhuman beings? Ghost Species is a prescient reminder that it’s not merely imperative that we solve the problem of climate crisis, it matters how. – Stephanie Convery

o Could bringing Neanderthals back to life save the environment? The idea is not quite science fiction

6. The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Affirm Press

This debut meshes real and imaginary. It revolves around the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary, led by the esteemed Sir James Murray – but the narrative is focused on the fictional Esme, one of the lexicographers who sorts out contributions sent worldwide for possible inclusion.

One day Esme finds a carelessly discarded word and rescues it; over the years she’ll add to her secret collection with others deemed unimportant by the grand and pompous men of letters. It’s a story as much about sexism and the suffragette movement as it is about the provenance of words. – Thuy On

o ‘All words are not equal’: the debut novelist who’s become a lockdown sensation

7. Show Me Where it Hurts by Kylie Maslen

Text

In a year that has had no shortage of incisive, wry and intelligent essay collections, Kylie Maslen’s Show Me Where it Hurts stands out. Maslen writes about her experience of chronic illness with generosity and warmth. While each essay begins from a place of lived experience, the collection covers a range of topics – from pop culture to aged care – and she brings the same depth to an essay about SpongeBob SquarePants as to a piece about the Australian economy.

Maslen delivers observations about the entrenched ableism in Australian society with a charming frankness that make this thought-provoking debut memorable. – Bec Kavanagh

o The idea of ‘too much information’ is bad for our health. It’s time we ditched it

8. Sad Mum Lady by Ashe Davenport

Allen & Unwin

I am, arguably, not the target audience – with my own children old enough to make the travails of parenting newborns a distant, somewhat repressed memory – but Ashe Davenport’s debut was a brilliant read that transcended any idea of genre or the narrow relevance of one’s own experience. First and foremost it’s a sharp, funny, frequently moving book of essays from a serious new writer.

Buy it if you have a new parent in your life who is looking for a more honest take on the experience; or buy it for that fan of personal essays in the Sloane Crosley/David Sedaris mode, looking to snort-laugh in horrified recognition. – Michael Williams

9. Almost a Mirror by Kirsten Krauth

Transit Lounge

Released in the early days of the pandemic, you may have missed this gem of a novel. A book about relationships, music, culture and youth, Almost a Mirror is set in the post-punk scene of 80s Melbourne (as well as the Blue Mountains, Sydney and Castlemaine).

There are echoes here of Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip in the descriptions of Melbourne, music, drugs – along with the men who are in thrall to them and the women left behind. Krauth’s gift is to drop you into a fully formed and realised world, and the devil is in the details: what kids in the 1980s were wearing, listening to, drinking, ingesting and smoking is on point. It would all be very nostalgic except for the tragedy that runs through.

A bonus: the structure is set up as a mixtape, with each chapter of the novel an 80s song. It will have you trawling through Spotify as you read. – Brigid Delaney

o Nick Cave, Andy Griffiths and the $10,000 suit: how Melbourne’s Crystal Ballroom launched a scene

10. Smart Ovens for Lonely People by Elizabeth Tan

Brio Books

Like her first book, Rubik (a novel of interconnected stories), Elizabeth Tan’s equally idiosyncratic follow-up is made up of 20 standalone tales that also touch on sci-fi, satire and fantasy. Smart Ovens for Lonely People is artful and fun as it explores pop culture in a futuristic but still recognisable setting. The title story deals with a talking, cat-shaped oven designed to soothe the downhearted.

Yet underneath the playfulness there’s poignancy in these stories. Their inventiveness and unpredictability add lustre and charm to the collection. You don’t know where Tan will go but she makes you want to follow. – Thuy On

11. Truganini: Journey Through the Apocalypse by Cassandra Pybus

Allen & Unwin

So much Australian history has miscast the Nuenonne woman Truganini as “the last of the Tasmanian Aboriginal race” and shaped her textured, fascinating life into a simple three-act tragedy. This cliched trope had her slipping between two worlds, the Indigenous and the British colonial. It overlooked her complexity, her resilience and her remarkable capacity to negotiate survival in what was, to the first Tasmanians, an apocalypse.

The historian and writer Cassandra Pybus restores Truganini’s agency in this rich, beautifully realised biography of one of the most significant Aboriginal women to experience and endure colonialism’s violent upheavals. – Paul Daley

o Truganini’s story has always been told as tragedy. She was so much more than that

12. The Animals in That Country by Laura Jean McKay

Scribe

The Animals in That Country is an uncanny book, in no small part because it was released in March and has a pandemic is at its centre. It follows Jean, a tough-talking older woman who lives and works in a rural wildlife park. When a new strain of flu sweeps the country – one whose main symptom is an ability to understand the language of animals – Jean flees her home, alongside a dingo named Sue, to try to track down her missing family.

McKay’s book is madcap and poetic by turns; concerned about exactly what constitutes the relationships between humans and animals, and how we see each other and interact in this world we share. – Fiona Wright

o The Animals in That Country by Laura Jean McKay review – an extraordinary debut

13. The Mother Fault by Kate Mildenhall

Simon & Schuster

Kate Mildenhall’s The Mother Fault amplifies the tension of motherhood in a gripping cli fi thriller. A near-future Australia is burdened by the increasing effects of climate change, its citizens living under the totalitarian rule of The Department.

When Mim’s husband goes missing, and The Department threatens to take her children, she embarks on a risky sea voyage in search of answers. Mildenhall’s novel is an intelligent, fast-paced and provocative about things to come. – Bec Kavanagh

o For women in lockdown with kids, it’s impossible to be seen as anything other than a mother

14. Song of the Crocodile by Nardi Simpson

Hachette

Watched over by wakeful ancestors, the Billymil family have lived in rural Darnmoor – “Gateway to Happiness” – for three generations, trying to carve out space for themselves in a world that does not want them. In town, simmering animosities take violent shape. Under the river bed, the Crocodile spirit is stirring.

It’s hard not to drown Song of the Crocodile in awed praise but this book deserves every skerrick of hype. That it is Simpson’s debut feels like a magnificent question: what else might she bring us? For now, just surrender to her storytelling, rich with Yuwaalaraay language and song. – Beejay Silcox

15. After the Count: The Death of Davey Browne by Stephanie Convery

Penguin Random House

Guardian Australia’s deputy culture editor, Stephanie Convery, has a great many past-times: she sings, she knits, she birds, she does extreme exercise – and she also boxes. It’s this personal connection that drew her to the story of Davey Browne: the 28-year-old boxer who was knocked out and died in the final minutes of a regional championship fight held at an RSL in western Sydney in 2015. Convery sets out to discover who was responsible for his death in this meticulously reported and balanced book, which blends fact, history and the voices of those involved with her own experience and passion for the sport.

Ultimately – unsurprisingly – there’s no one person to point the finger at (“not I, says the referee … not us, says the angry crowd … not me, says his manager”, as Bob Dylan would put it), but instead a widespread misunderstanding of the rules, and a larger systemic issue: the sporting world has been glossing over the symptoms and risks of repeated brain injury for far too long. This beautifully written and well-argued book had me from start to finish. – Steph Harmon

o Stephanie Convery: the sports world knows concussion can kill. So why does no one talk about it?

16. Infinite Splendours by Sofie Laguna

Allen & Unwin

Sofie Laguna’s achievement in her novel Infinite Splendours makes my hair stand on end. She is so deft at balancing the darkest material with luminosity that it seems impossible to tell you the core subject matter of the book and still have you believe that it is ultimately uplifting.

Written here, it would be confronting, possibly off-putting but in Laguna’s hands the human condition she excavates is wrapped in her extraordinary compassion. Suffice to say there is a terrible betrayal against a child, then a painstaking exposition of how that betrayal ripples along the long arc of a life. Brilliant. – Lucy Clark

o Infinite Splendours by Sofie Laguna review – a sad and sublime tale of trauma and art

17. Future Girl by Asphyxia

Allen & Unwin

Future Girl blends art, activism and storytelling in a compelling young adult climate crisis narrative. Piper, a deaf teenager growing up in a near-future Melbourne, has spent her life trying to pass as hearing. But when an oil crisis plunges the city into an environmental and economic shutdown, Piper has the opportunity to rethink what skills (and friendships) are truly necessary to live.

Asphyxia has created an extraordinary book, filled with her own artwork. Reading it is like dipping into someone’s diary – intimate, engrossing, at times confronting. Future Girl is a reminder that art is not only a comfort but a provocation of how we might reimagine the world. – Bec Kavanagh

18. The Case of George Pell: Reckoning with Sexual Abuse by Clergy by Melissa Davey

Scribe

The journalist, Walkley award winner and Guardian Australia’s Melbourne bureau chief, Melissa Davey, spent years diligently covering the investigation, trials, appeals and eventual acquittal of Cardinal George Pell on charges of child sexual abuse for this news outlet. In this, her first book, she draws together all the evidence and counter-arguments, her observations, details of the courtroom procedures and her experience of them and the public’s reaction to her reporting.

She is methodical, diligent and direct – and studiously avoids giving her opinion on the court’s decisions or her beliefs about Pell’s guilt or innocence. As a consequence, her book is a thorough, detailed, and tremendously important document of one of the most high-profile court cases in recent memory, and a must for anyone who wants their own understanding of what happened, as Davey says, “to be, at the very least, informed by the evidence”. – Stephanie Convery

o Defending George Pell: ‘I believe Pell’s a good man’

19. The Fogging by Luke Horton

Scribe

The Fogging is one of those books that creeps up on you: it’s quiet, often understated, and the dramas it’s concerned with are small, almost claustrophobic. But I’ve not been able to stop thinking about it. .

The novel follows the protagonist, Tom, over the course of a short holiday in Bali with his partner, Clara, as he slowly unravels and the dynamics of their relationship shift and change – and it’s a deeply enthralling, deft gem of a book. – Fiona Wright

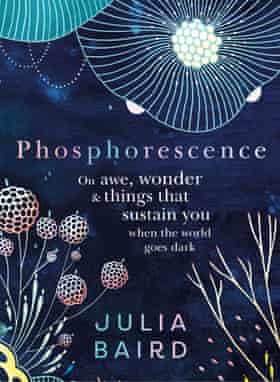

20. Phosphorescence by Julia Baird

HarperCollins

If ever there was a book this year that was uncannily perfect for the moment, it was Julia Baird’s Phosphorescence. Just as the world fell further, further into a dark pit in August, Baird’s book brought wonder and grace and meaning and comfort, all the things we needed right then. It has generosity, too.

Among the stories she has gathered to pique the reader’s sense of awe, Baird shares her personal experience with cancer but not in a mawkish way. It’s purely in service to the idea that humans have the ability to dig really deep, and to find beauty everywhere. An inspiration. – Lucy Clark

o Julia Baird on finding light in the dark: ‘Coronavirus will leave a massive psychic scar’