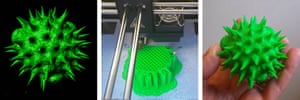

As a former secondary school science teacher, Oliver Wilson knows the challenges of communicating big, complex issues. Now, the palaeoecologist is reaching global audiences with a project that brings to life the microscopic world of pollen by producing giant 3D-printed models from high-quality scans of pollen grains.

“Being able to identify pollen is important for many reasons,” he says. Because they can survive millions of years and are tiny and tough, they can help track changing climate patterns, reveal the quality of honey and even provide forensic evidence at crime scenes. “But I love seeing what else people do with the models,” he says. Already they have been used by bee ecologists in Brazil, US school teachers and Irish archaeologists, among others.

Wilson’s quest to provide open access to scanning and printing pollen grains in 3D began after winning some money on the online teaching platform I’m a Scientist, Get Me Out of Here for his success in engaging students. He was determined to use the money to share his enthusiasm for pollen, which, he says, most people overlook as dust, except when they have hay fever. He recognised that providing open-access giant models of these tiny unique shapes would have enormous uses for science and education.

He has since created a fast, free and accessible way for anyone to print outsize replicas of pollen grains, magnified 2,500 times, via his online 3D Pollen Project. So far, pollen from 35 plant species has been scanned and modelled and he is ready to get to work on the next 100 species sent to him from around the world, including from Europe, Colombia, Tanzania, Ecuador and Mongolia.

“It was a long process of trying to figure out how to do it well. But we’re there, and so far they’ve been downloaded 2,500 times in 45 countries,” he says. “I’d like to create a broad spectrum with each branch of the tree of plant life represented, for researchers, schools and other users.”

The project has found fans beyond the world of science. “I’ve had emails from mechanical engineers in Israel, fashion designers in Denmark, others in China, the Netherlands … it would be good to make mint pollen chocolates too! 3D printing also has huge potential to revolutionise teaching, especially while social distancing.”

Wilson is now a final-year PhD student at the University of Reading, researching, by studying pollen, how climate change and indigenous cultures have influenced critically endangered araucaria forest trees in southern Brazil. He describes pollen shells as “the diamonds of the plant world, one of nature’s toughest materials. They act like a time machine, lasting for millions of years. They tell us how forests are shaped by climate change and people.”

To create the 3D Pollen project, Wilson collaborated with Hull University and also had help from Cardiff University’s Bioimaging Research Hub and Dr Katherine Holt, a senior lecturer at Massey University in New Zealand who first developed a set of accurate, 3D-printed scale models of pollen up to 3,000 times their actual size. “The idea has received a lot of interest and uptake, but that should be credited to Oliver, he’s built the profile for the concept,” she says.

Wilson’s first scans included pollen from several wind-pollinated European trees that are among the worst for inducing hay fever: oak, birch, alder, hazel, willow, pine and small-leaved lime. His models also include pollen from several important insect-pollinated wild flowers, including from an ox-eye daisy collected in Sweden that looks like a naval mine, that of a vibrant pink coneflower from Chicago botanic garden, plus grains from English meadow clary, ivy, fat hen, wormwood, meadowsweet, knapweed, heather and autumn hawkbit. Most of the pollen grains he has scanned and modelled are 100th to 1000th of a cm in size.

Alastair Culham, associate professor of botany at the University of Reading, said: “3D printing has great potential in teaching. It’s the modern equivalent of the famous Blashcka glass flowers at Harvard. They were intended as scientific educational objects primarily, so fall into the same category as 3D printed objects now. They have become works of art but they are very technically precise models and the product of a unique combination of technology, skill and practise.

“While printed technology might have the feeling of a mass-market product, those models still need cleaning and de-burring and there is a lot of skill in making the 3D computer model,” he adds.

Tony Hayes at Cardiff Univeristy’s bioimaging hub has made 60 pollen models for science centres, plus a prehistoric swamp fossil insect, a giant head of a red ant and a zebra fish larva. “We also created pollen models from an archaeological dig called Footprints in Time, from 5,000 years ago,” he says.”

Dr Alex Ball, head of imaging and analysis at the Natural History Museum in London, says exhibits of all sizes are now often being 3D scanned and printed or magnified.

“Some exhibits are too small or fragile to handle, whereas these can be made cheaply and replaced easily,” he says. “This is one way of making a collection more accessible. We are exploring how to use them to teach visually impaired people about microscopy. This includes 3D prints of sand and sugar grains, insect heads and coins.”

The museum recently worked with artist Emma Gibson on scanning, magnifying and printing grains of sand from a beach, turning them into car-sized sculptures called Quicksand, exhibited at Selfridges in London and destined for the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Dr Paul Wilson at the University of Warwick, who hosted an online symposium this week on the future of 3D visualisation in cultural heritage which brought together museum experts and scientists, says: “Covid is forcing museums to do a whole plethora of different levels of immersion and think in new ways.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features