The computer chip industry has a dirty climate secret

As demand for chips surges, the semicondutor industry is trying to grapple with its huge carbon foot print

The semiconductor industry has a problem. Demand is booming for silicon chips, which are embedded in everything from smartphones and televisions to wind turbines, but it comes at a big cost: a huge carbon footprint.

The industry presents a paradox. Meeting global climate goals will, in part, rely on semiconductors. They’re integral to electric vehicles, solar arrays and wind turbines. But chip manufacturing also contributes to the climate crisis. It requires huge amounts of energy and water – a chip fabrication plant, or fab, can use millions of gallons of water a day – and creates hazardous waste.

As the semiconductor industry finds itself increasingly under the spotlight, it is starting to grapple with its climate impacts. Last week Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, the world’s largest chipmaker, which supplies chips to Apple, pledged to reach net zero emissions by 2050. The company aims to “broaden our green influence and drive the industry towards low-carbon sustainability”, said the TSMC chairman, Mark Lui.

But decarbonizing the industry will be a big challenge.

TSMC alone uses almost 5% of all Taiwan’s electricity, according to figures from Greenpeace, predicted to rise to 7.2% in 2022, and it used about 63m tons of water in 2019. The company’s water use became a controversial topic during Taiwan’s drought this year, the country’s worst in a half century, which pitted chipmakers against farmers.

In the US, a single fab, Intel’s 700-acre campus in Ocotillo, Arizona, produced nearly 15,000 tons of waste in the first three months of this year, about 60% of it hazardous. It also consumed 927m gallons of fresh water, enough to fill about 1,400 Olympic swimming pools, and used 561m kilowatt-hours of energy.

Chip manufacturing, rather than energy consumption or hardware use, “accounts for most of the carbon output” from electronics devices, the Harvard researcher Udit Gupta and co-authors wrote in a 2020 paper.

A global shortage of high-end chips, as the pandemic boosted demand for electronics and Covid outbreaks closed fabs, has increased focus on the industry.

In a tight market, automakers found themselves at the back of the chip queue, far behind much bigger-scale semiconductor customers such as Apple, who use the chips to give computing power to their smartphones, laptops and other devices. GM halted production in several of its North American factories this month, while Toyota said it would cut its carmaking by 40% in September.

In an attempt to increase production, many countries are embarking on big programs to boost the industry.

The Chips for America Act proposes $52bn in funding over five years for the US semiconductor industry. The EU has forwarded its own legislation aimed at increasing its share of the global chips market to 20% by 2030. The European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, called it “a matter of tech sovereignty” in her State of the European Union address last week.

These ambitions line up a potential clash with international climate goals. Both the EU and US aim to get halfway to net zero carbon emissions by 2030, and to net zero by 2050. And as the semiconductor industry grows, so too will its carbon footprint.

However, amid pressure from investors and electronics makers keen to report greener supply chains to customers, the semiconductor business has been ramping up action on tackling its climate footprint.

“Recently, I started seeing our effects on the environment completely come to the forefront,” said Sohini Dasgupta, principal design engineer at ON Semiconductors.

Two years ago, she said, the industry “was sitting on the fence, in the middle of the pack, saying: ‘Yes, sustainability is important, but we don’t know what to do with it'”. But now she sees movement: “Every day it pops up in our emails, what our company’s doing, what other companies are doing,” she said.

The rise of ethical investing has helped, according to Mark Li, a semiconductor analyst at the investment firm Bernstein. Fund managers increasingly market “green funds” and investors are asking more questions about companies’ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) impact. “Over the last three years, the voice of ESG investment is much louder than before,” Li said. Ultimately, this changes how companies behave, he added.

Greater availability of renewable energy is helping chipmakers reduce their carbon footprint. Intel made a commitment to source 100% of its energy from renewable sources by 2030, as did TSMC, but with a deadline of 2050.

Energy consumption accounts for 62% of TSMC’s emissions, said a company spokesperson, Nina Kao. The company signed a 20-year deal last year with the Danish energy firm Orsted, buying all the energy from a 920-megawatt offshore windfarm Orsted is building in the Taiwan Strait.

The deal, which has been described as the world’s largest corporate renewables purchase agreement, has benefits for TSMC, said Shashi Barla, renewables analyst at the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie. As well as guaranteeing a clean electricity supply, it pays a wholesale cost and removes itself from price shocks, “killing two birds with one stone”, he said.

TSMC’s actions have the potential to influence the rest of the industry, said Clifton Fonstad, professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT, “other manufacturers are likely to follow its lead”.

As well as switching to renewables, chipmakers could also implement efficiencies in fabs, said Peter Hanbury, a semiconductor manufacturing expert at the management consultancy Bain & Company. A chip fab is basically “a gigantic warehouse with a clean room inside”, he said, and to cut emissions, “the easy part is the facility itself”.

Fabs could be more efficient in regulating air and water temperature, humidity, and pressure. They could segment warehouses so one production line had high pressure, and another lower, using less energy than keeping the entire warehouse at a high pressure.

They could capture more data and use machine learning to turn tools off when they weren’t being used, said Huili Grace Xing, an engineering professor at Cornell University who works on semiconductor materials.

There is also innovation aimed at tackling the worst-polluting materials used in making semiconductors. The chip industry uses different gases during the production process, many of which have a significant climate impact.

TSMC said it had implemented scrubbers and other facilities to treat gas emissions. But another route is replacing “dirtier” cleaning gases that clean the delicate tools in semiconductor manufacturing, said Michael Pittroff, a chemical engineer working on semiconductor gases at Solvay Special Chemicals.

In industrial tests over the last six years with about a half dozen chipmaker clients, Pittroff said, he and his team had replaced more polluting gases with “cleaner” fluorine, with a lower global warming impact.

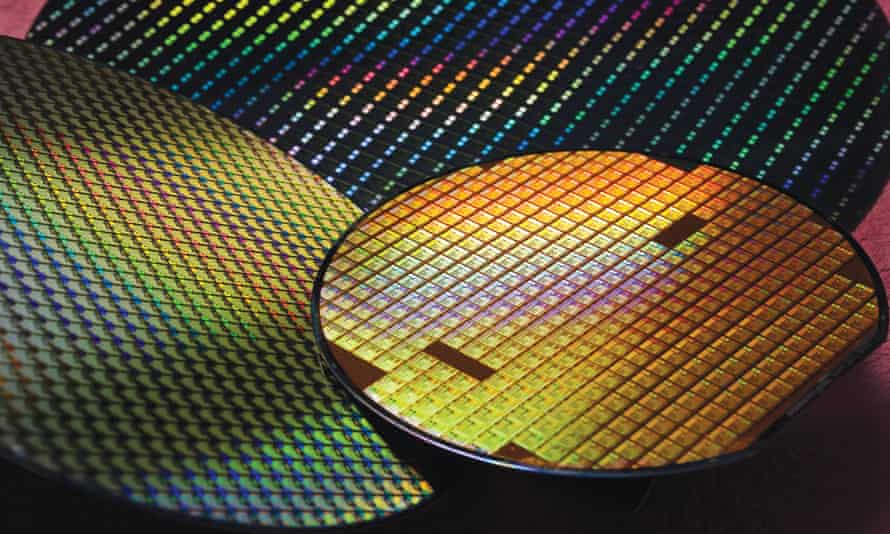

Other companies target the gases that are used to etch patterns onto and clean the silicon surface of a wafer – the thin piece of material used to make semiconductors. Paris-based industrial gases company Air Liquide, for example, has come up with a line of alternative etching gases with lower global warming impacts.

But replacing gases will be a challenge: anything that touches the silicon wafer, such as an etching gas, is really hard to alter once a fab is operating, said Hanbury. The process involves a huge amount of precision. Fabs have to place up to 100m transistors on a postage-stamp sized wafer and need to do it perfectly. It takes four to five years for fabs to develop a recipe for this and “once you set it, you basically never want to change it”, Hanbury said.

Some experts believe chipmakers will start to modify their processes to incorporate greener gases, especially if the big players make a move. “If TSMC switches, I am sure the others will,” said Fonstad. “If TSMC doesn’t, then other manufacturers may switch to show they are better than TSMC.”

To some observers of the chip business, the determination to clean up the industry seems real. The vast demand for chips at the moment will only help the semiconductor industry embrace sustainability goals, said Li.

“They have very good margins, and make lots of money. So even though all these green carbon measures would have a cost, they can afford it. And increasingly, customers are willing to pay more for a greener device,” he said.