The mass die-off of thousands of songbirds in south-western US was caused by long-term starvation, made worse by unseasonably cold weather probably linked to the climate crisis, scientists have said.

Flycatchers, swallows and warblers were among the migratory birds “falling out of the sky” in September, with carcasses found in New Mexico, Colorado, Texas, Arizona and Nebraska. A USGS National Wildlife Health Center necropsy has found 80% of specimens showed typical signs of starvation.

Muscles controlling the birds’ wings were severely shrunken, blood was found in their intestinal tract and they had kidney failure as well as an overall loss of body fat. The remaining 20% were not in good enough condition to carry out proper tests. Nearly 10,000 dead birds were reported to the wildlife mortality database by citizens, and previous estimates suggest hundreds of thousands may have died.

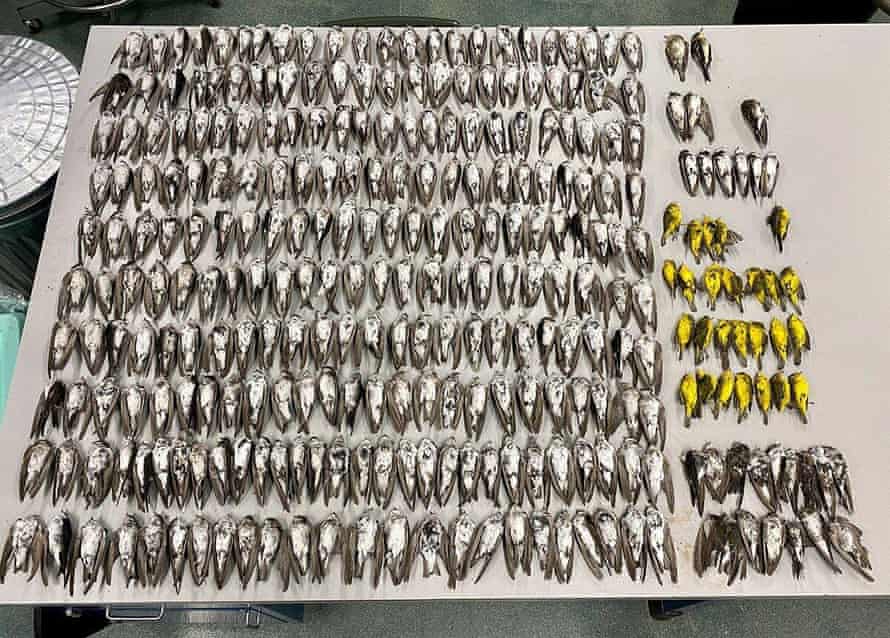

“It looks like the immediate cause of death in these birds was emaciation as a result of starvation,” said Jonathan Sleeman, director of the USGS National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wisconsin, which received 170 bird carcasses and did necropsies on 40 of them. “It’s really hard to attribute direct causation, but given the close correlation of the weather event with the death of these birds, we think that either the weather event forced these birds to migrate prior to being ready, or maybe impacted their access to food sources during their migration.”

The first deaths were reported on 20 August at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, with accounts of birds appearing lethargic and congregating in groups before dying. Most deaths happened around 9 and 10 September during a bout of cold weather that probably meant food was particularly scarce. In a weakened state, the birds seemed to become disorientated, flying into cars and buildings, some dying on impact and others landing on the ground, subsequently dying from cold temperatures or being eaten by predators.

“We’re not talking about short-term starvation – this is a longer-term starvation,” said Martha Desmond, a professor in the biology department at New Mexico State University (NMSU), who collected carcasses. “They became so emaciated they actually had to turn to wasting their major flight muscles. This means that this isn’t something that happened overnight.”

The birds probably would have started their migration in poor condition, which could be related to the “mega-drought” in the south west of the country. “Here in New Mexico we’ve seen a very dry year, and we’re forecast to have more of those dry years. And in turn I would say it appears that a change in climate is playing a role in this, and that we can expect to see more of this in the future,” said Desmond.

“I think it’s just very sad,” she added. “Especially the thought that we are seeing some long-term starvation in some of these birds.” Sleeman could not say if this event was directly related to climate change but acknowledged that it is making extreme weather events more likely.

Desmond previously described seeing so many individuals and species dying as a national tragedy. Most of the birds were insect and berry eaters that migrate from tundra landscapes in Alaska and Canada to winter in Central and South America. Most of them have to stop and refuel every few days on their migration.

Concerns were raised about wildfires in California causing birds to re-route their migration inland over the Chihuahuan desert but necropsies showed no smoke damage in their lungs. The centre also ran tests for contagious bacterial and viral diseases, parasites and evidence of pesticide poisoning, all of which came back negative.

Allison Salas, a graduate student at NMSU, said the volume of carcasses she had collected had given her chills. She said: “The fact that we’re finding hundreds of these birds dying, just kind of falling out of the sky is extremely alarming.”

Desmond’s team is hoping to get funding to support more research into mass die-offs in birds so they can better monitor what is happening. Sleeman agreedthat large-scale mass mortality wildlife events are happening more frequently. “It’s something we definitely need to keep track of,” he added.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features