Microsoft drew widespread praise in January this year after Brad Smith, the company’s president, announced their climate “moonshot”.

While other corporate giants, such as Amazon and Walmart, were pledging to go carbon neutral, Microsoft vowed to go carbon negative by 2030, meaning they would be removing more carbon from the atmosphere than they produced.

By 2050, Smith added, the company was aiming to remove all of the carbon they had ever emitted since being founded in 1975.

The firm’s promises won plaudits from conservationists and climate conscious Microsoft employees, but also attracted big questions: how are they going to actually deliver this?

Much of its plans lean on nascent technology. Critics, meanwhile, see the move as a gamble aimed at justifying Microsoft’s ongoing deals with fossil fuel firms.

Microsoft releases less carbon a year than Amazon and Apple, but more than Google. The company has 150,000 employees across offices in more than 100 countries, and is still focused on developing the software and consumer electronics that made them a household name – Windows, PCs, Xbox. But after a temporary slump following their heyday in the 1990s, they have also once again become innovators, developing world-leading artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud computing products.

The company hopes to bring that innovative approach to its climate policies, in part by widening how it calculates its carbon footprint, beyond most corporate responsibility plans. Historically, Microsoft has only counted those emissions that fall within the scope of their own business operations – employee travel, company vehicles, heat and electricity in company buildings, and so on.

From now on, it plans to take responsibility for the emissions produced by its entire supply chain, including the full lifespan of the products it makes and the electricity that customers may consume when using its products.

Meanwhile, increasing the scrutiny on Microsoft’s plan are its dealings with fossil fuel companies, which have been highlighted by some as evidence of hypocrisy as it makes climate pledges. In 2019 alone, the technology company had entered into long-term partnerships with three major oil companies, including ExxonMobil, that will be using Microsoft’s technology to expand oil production by as much as 50,000 barrels a day over the coming years. The staggering amount of carbon this would release into the atmosphere would not be included on Microsoft’s expanded carbon ledger.

For Microsoft, however, partnering with oil companies is not considered hypocritical. The company is hedging its climate bets on carbon capture and removal technologies that they believe will be able to offset some of the environmental harm caused by fossil fuels during the transition to a more sustainable future, despite such technologies being still in their nascent stages and not yet proven to work at scale.

Those who devised the plan at Microsoft argue that they are responding directly to a new reality: cutting emissions is not enough and all routes to non-catastrophic temperature increase will also require removing carbon from the atmosphere. So, as well as shifting to a 100% supply of renewable energy for all of their data centers, buildings and campuses by 2025, Microsoft outlines a number of carbon reduction methods it is backing to try and hit its bold targets.

Protecting forests

To begin, Microsoft will focus on protecting forests and planting trees to capture carbon. This strategy has long been used to offset emissions, but Microsoft is hoping to improve their outcomes by using remote-sensing technology to accurately estimate the carbon storage potential of forests to ensure no major deforestation is occurring in their allotments. To achieve these goals, Microsoft will be partnering with Pachama, a Silicon Valley startup that will survey 60,000 hectares of rainforest in the Amazon, plus an additional 20,000 hectares across north-eastern states of the US for the company.

According to Kesley Perlman, a climate campaigner at the forest conservation NGO Fern, Microsoft’s commitment to hi-tech reforestation is encouraging, but she stressed that conservation is a complex, multifaceted process that goes beyond technical issues. “It’s not only about how much carbon a forest can hold but also who traditionally uses the forest, how they might be kept out, and how biodiversity will be prioritized,” she said.

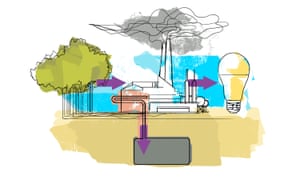

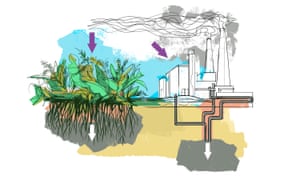

Biomass energy carbon capture storage

Microsoft will initially focus on nature-based solutions to reduce their carbon footprint over the next five or so years. But in order to start drawing more carbon from the atmosphere than they emit by 2030, it will need to shift to technology-based solutions that can scale up and accelerate carbon removal.

To this end, Microsoft is betting on biomass energy carbon capture storage, otherwise known as BECCS, to transform how energy is generated. Instead of burning coal, a BECCS power plant burns biomass, like wood chips. The carbon produced when burning the biomass is captured before it is released into the atmosphere and then injected at a very high pressure into rock formations deep underground. Not only does this remove carbon from the natural cycle, the biomass absorbs CO2 as it grows.

A world powered by biofuel, however, raises two looming questions. First, scientists are not yet certain if biomass energy will be carbon neutral.

The second concern is that the transition from coal to biofuel would require setting aside vast tracts of arable land – some estimates say one to two times the size of India. According to climate campaigner Perlman this would mean that the energy industry would probably have to compete with food production in a world where 10 billion people will need to be fed, while vastly enlarging industrialized plantations and reducing biodiversity. “We would likely see massive land use change and massive private purchases of land, the knock on impacts of which could be quite dangerous,” she said.

Direct air capture

Perhaps the most futuristic of the technologies outlined in Microsoft’s carbon negative plan is direct air capture (DAC). This involves machines that essentially function like highly efficient artificial trees, drawing existing carbon out of the air and transforming it into non-harmful carbon-based solids or gasses.

While the image of air-conditioner-like machines sucking carbon out of the air is captivating, capturing CO2 directly from the atmosphere requires a lot of energy and is very expensive. In 2011, extracting carbon from the air cost $600 a ton of CO2. In 2018, estimates brought this down to anywhere between $94 to $232 a ton. But given that Microsoft expects to emit 16m metric tons of carbon this year, if they were to reach carbon zero using only DAC, their bill might cost as much as $3.5bn.

According to Lucas Joppa, chief environmental officer at Microsoft, a large part of the reason why carbon removal remains so expensive is because the markets around these technologies are still immature. The company’s strategy over the coming decades is maturing these markets through intensive and directed investment. “We’re making a bet on certain technologies that don’t exist at the scale or price point we need them to,” he said. “But if we want to get them, we need to start investing.”

The company, he said, already has a model for raising funds internally to support climate innovation. In July 2012, Microsoft became one of the first companies to institute an internal carbon price, charging different divisions in the business $15 a metric ton of carbon emitted. The funds raised were then used to pay for sustainability improvements, which helped the company achieve their goal of going carbon neutral.

Previously, this carbon price only extended over emissions Microsoft was directly responsible for. According to their new plan, in July this year Microsoft will extend this internal carbon price over emissions produced across direct and indirect emissions. The increased revenue raised from the expanded internal carbon tax, along with a $1bn climate innovation fund, will be used to invest in capture and removal technology. “What we’re going to do is put this money in the market in a way that is highly additional,” Joppa said. “This is how we’re going to get nature-based solutions and tech solutions at a price point and scale we need.”

Microsoft’s plan for intensive investment in this industry is exciting for those working in the field. Klaus Lackner, a theoretical physicist working on DAC, has been arguing since the 1990s that carbon removal is the only feasible way to stop significant temperature rises. “We’ve shown that this method is technologically feasible, but nobody has wanted them,” he said. “Microsoft have said ‘we get it’. It will cost them money, but it will allow the technologies to come online and for the next company to follow their footsteps.”

While the technologies that Microsoft are betting on are still in their nascent stages, in the past few years there has been some encouraging progress in the negative emissions industry. Lackner and Arizona State University recently signed a deal with Silicon Kingdom, an Irish-based company, to manufacture his carbon-suck machines. The plan is to install them on wind and solar farms, and then sell the captured carbon to beverage companies to make carbonated drinks. In the UK, Drax power plant, which was once among Europe’s most polluting, transitioned from coal to biofuel this year.

But many attempts at scaling carbon negative projects have also failed. The Kemper Project in Mississippi, which was billed as America’s flagship carbon capture project, was abandoned in 2017 – it was $5bn over budget, three years late and still not operational.

Moral hazard

Given the not insignificant risk of failure, some propose that relying on nascent or future technology as a solution to the climate crisis represents a moral hazard – the promise of carbon removal functions as an incentive for governments and major polluters to not change their behavior now.

According to Chris Adams, a tech worker who organizes an online community of technology professionals agitating for climate action from within the industry, the fact that Microsoft is still partnering with big oil companies demonstrates the moral hazard in action. “They are protecting the fossil fuel industry from changing while the rest of the world will pay most from this gamble if it fails in the long term,” he said.

Adams added that many of the encouraging ideas around carbon reduction in Microsoft’s plan have come from internal organizing from concerned employees, but that this mostly goes unacknowledged in Microsoft’s official vision. Emphasizing future technology while overlooking activism in the present, Adams said, represents a certain way of approaching problems that is typical of technology companies. “If you have spent the last 10 years amassing influence by approaching most problems with technology it’s understandable you see all problems through this lens, particularly if you don’t have to have conversations about power,” he said.

When asked about this concern by the Guardian, Microsoft’s Joppa responded that in the short term, the energy demands of a growing global population will probably still need a mix of renewable and traditional energy sources. By remaining in discourse with these industries, he said, Microsoft hopes to help them change and transition to a better model in the future. “It’s extremely hard to lead if there’s no one there to follow,” he added.

As to whether the technology outlined in their plan will scale, he said there is inherent risk, but this is why they call it a “moonshot”. “When it comes to our plan it’s not like we’ve got it all figured out,” he said. “We’re just trying to do what the science says the whole world needs to do. There’s really no other choice.”

This story is a part of Covering Climate Now’s week of coverage focused on Climate Solutions, to mark the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. The Guardian is the lead partner in Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration committed to strengthening coverage of the climate story.