For some time this pandemic will focus almost all of our attention. It is a tragedy that will play out differently in different parts of the world; the poor world will suffer more than the rich one. We will see it as a potential turning point, a portent, a sign that we should have cared more and prepared better. However, human progress was slowing before this pandemic began, and our world will continue to slow down for some time to come – long after the pandemic has ended. I mean slowing down in almost every way that matters. Because the slowdown was itself slow, we had hardly noticed it. In fact, many people thought that we were still accelerating.

For older generations everything had changed so fast, but in fact that fast pace ended years ago. There is no normal for us to return to; the normality of economic growth is an illusion.

A century ago the pace of change was faster than it had ever been and would become faster again. During the Spanish global flu pandemic of 1918-19, carbon emissions fell by 14%. Industrial production and consumption slowed down dramatically. But then, just a year later when most of the sick had recovered, production and pollution rose by 16% in the year to 1920. Back then we were on the upswing. We were seeing ever faster population growth worldwide; back then a pandemic could not slow us down for long.

In 1918, influenza had a far greater effect on worldwide trends in industry, production and consumption than the first world war – which was a war almost entirely confined to Europe. A century ago that worldwide influenza pandemic killed tens of millions of people, no one knows for sure how many. Yet today when we look back at demographic and economic trends, that last great pandemic appears as a small blip with few long-term consequences.

Over the past two centuries, the number of people alive in the world has doubled and doubled and doubled again; from 1 billion shortly before 1820, to 2 billion by 1926 and 4 in 1974; it will be 8 billion in 2023. But crucially the rise is slowing. As I write, our numbers are rising by 80 million people a year. Next year it will be by 79 million, the year after by 78 million. We are still growing in number as a species, but that growth has been slowing for more than half a century already.

We do not yet know what effect the current pandemic will have on worldwide demographics. But it is actually slightly more likely to increase future populations than decrease them. If the actions of governments, or at least of most governments, make people feel more insecure, economically and socially, then younger people may in the near future have more children than they would have had; and the pandemic will, counterintuitively, very slightly increase the total future population.

Security matters. In normal times this point has to be laboured because many readers of newspapers in affluent countries do not realise how precarious the safety net is for most people in the world. But today they are feeling as most people in poorer countries feel most days. Such insecurity played a part in the great acceleration in human population that began more than two centuries ago. It is worth looking back before looking forward.

In 1859 Charles Darwin wrote about “the numerous recorded cases of the astonishingly rapid increase of various animals in a state of nature, when circumstances have been favourable to them during two or three following seasons”. Darwin used examples ranging from minuscule seedlings to giant elephants; he discussed the very rare cases in nature when exponential population growth occurred in a species. Darwin had no way of knowing it, but he was writing just as his own species was about to have its favourable seasons.

The word “slowdown” was first used in the 1890s, with its meaning being to go forward more slowly. Our current belief systems – economic, political and sociological – are all built on assumptions of rapid future technological change and perpetual growth. Yet even since the 1930s, technological change has slowed; the rate of economic growth has slowed every decade after the 1950s; population growth similarly has slowed since before the 1970s; and since at least the 1990s we have started to behave more like our parents again. By the 2010s we (at least in the rich world) were no longer seeing each generation better-off than the one before.

The general slowdown we are living through is advantageous. Recognising this requires us to shift our fundamental view of change, innovation and discovery as unalloyed benefits. We need to stop expecting ceaseless technological revolutions. We need to worry about what mistakes we will make if we carry on assuming that slowdown is unlikely and new great shifts lie just around the corner.

The time has come to properly contemplate what will happen if things stay much the same as they are now, while the rate of change simply slows down.

An era is ending – and this was obvious years before the pandemic arrived. The great acceleration that has occurred in recent generations created the culture in which we still live. It created our current expectation for a particular kind of progress. By “us” I mean the large majority of older people now living on Earth, those who have for the most part seen their health, housing and workplaces improve, those who had seen both absolute and relative poverty recede, but who now have a sense that their children’s generation will not be better off than they themselves are, those who are feeling a sense of let-down due to slowdown.

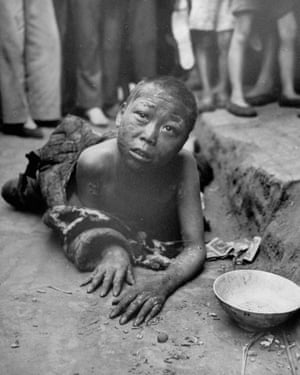

The alternative to slowdown is unimaginably bad. If we do not slow down, there is no escape from disaster far worse than a pandemic. We would wreck the planet we live on. Slowdown means we need not fear the nightmare scenario of worldwide famine depicted at the end of Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s 1968 book The Population Bomb, in which they concluded of India that its people should be allowed to starve: “Under the triage system [suggested by them] she [India] should receive no more food.” This kind of brutal conclusion was rife in the recent past. Images of out-of-control acceleration became commonplace. That was just half a century ago, at the peak of human population acceleration.

Although now may not be the time to point it out, the frequency and severity of disaster are both falling. The great Chinese famine of 1958-61 was worse in its effect than any of the earlier terrible huge Indian famines, or the east Africa famine of the 1980s. But the flu pandemic of 40 years before that famine had been worse still in terms of millions of deaths.

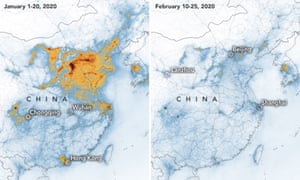

Today almost everything is increasing at a slower pace. Prior to the 2020 pandemic, the four great exceptions were: university graduates enrolled worldwide, consumption of goods, carbon pollution and air flights. They have all suddenly slowed due to the pandemic. Before January of this year they all appeared to be rising exponentially and uncontrollably. Today it is even possible that worldwide temperature will not rise in 2020 in the way it rose in 2019, as a reaction to reduced pollution.

Outside brief periods of wartime and pandemic, the global rates of population growth have exceeded 1% every year since 1901. However, according to the latest UN estimates published in June 2019, they will now almost certainly fall below that level by 2023, then quickly drop to below 0.9% annual growth around the year 2027. Everything was slowing down already, everything will still slow down when the current crisis ends. But the slamming on of the brakes on the train we were travelling on might, at the very least, wake us out of our stupor.

o Danny Dorling is the author of Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration – and Why It’s Good for the Planet, the Economy, and Our Lives, published 14 April (GBP14.99, Yale).