On the banks of the Pripyat River lies a forest. On a crisp winter afternoon with an expansive blue sky above and hardened snow underfoot, the area is criss-crossed with the tracks of hares, deer and wolves. This is the south-eastern tip of Belarus, home to sleepy villages steeped in tradition, where people hang their Christmas trees upside-down from the ceiling and eat raw pig fat as an afternoon snack.

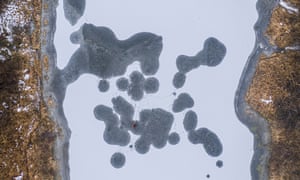

It is also part of Polesia, Europe’s largest wilderness. More than two-thirds the size of the UK (18m hectares) and spread across Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and Russia, in spring this brittle landscape blooms into a labyrinth of gigantic bogs and swamps that supports large populations of wolves, bison, lynx and 1.5 million migratory birds. It has been called “the Amazon of Europe” for its extraordinary biodiversity.

However, unlike its Brazilian cousin, this region is not best-known for its wildlife but something more sinister. In April 1986 this forgotten part of the Soviet Union made headlines after reactor 4 of the Chernobyl power plant blew up. The explosion cast a long shadow over Belarus, which absorbed 70% of the escaped radiation, making it one of the most contaminated places on Earth.

Now another catastrophe could be about to befall its people: the construction of the E40 waterway, a 2,000km (1,240-mile) inland shipping route linking the Black Sea and the Baltic that would slice through the wilderness and involve dredging inside the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Experts say this will destroy vast ecosystems and stir up radioactive sludge that accumulated on the bottom of the river following the explosion, potentially contaminating the drinking water of millions of people.

Dredging is due to start in the coming months following what campaigners have called a “quick and dirty” feasibility study that failed to consider the potentially catastrophic loss of biodiversity, radioactive contamination of drinking water, or loss of carbon from draining wetlands.

“We call E40 the death of Polesia. It would completely kill the south of the country,” says Alexandre Vintchevski, founder of APB-BirdLife Belarus, the country’s largest wildlife NGO. “Very few people know we have our own mini Amazon in Europe which is threatened by the construction of a waterway that no one has heard of.”

Linking the Black and Baltic seas

The ambition to link the Black and Baltic seas dates back thousands of years. The ancient Greeks knew about this region and thought it must have been a sea because there was so much water, while Vikings paddled through Polesia’s rivers during repeated attacks on Constantinople.

Small vessels can already pass through regulated stretches of the route but the rivers would need to be significantly broadened, with dams and dykes built and meanders cut off to allow ships at least 80 metres long to pass. The water will need to be at least 2.5 metres deep along the whole route. Up to seven million tonnes of cargo (mainly oil, fertilisers and wood) would pass through each year.

The E40 would stretch from Gdansk in Poland to Kherson in Ukraine, impacting five rivers en route: the Vistula, the Bug, the Pina, the Pripyat and the Dnieper, according to the feasibility study led by the Maritime Institute in Gdansk. At its closest it would pass only 2.5km from the Chernobyl nuclear reactor, potentially contaminating a reservoir downstream that provides water for 2.8 million people in Kyiv.

The E40 project is being pushed by a coalition of organisations and government ministries from Belarus, Poland and Ukraine, which is being led by the the Dnieper-Bug Republican Unitary Maintenance and Construction Enterprise. A coalition of wildlife organisations led by APB-BirdLife Belarus, Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and the National Ecological Centre of Ukraine is trying to stop the E40 going ahead.

One of Europe’s least spoilt waterways

The Pripyat river is one of the least spoilt waterways in Europe and is an integral part of the biodiversity of Polesia. More than 90% of all birds in Belarus are found in Polesia (which comprises the southern third of the country) and there are a number of unique ecosystems, including floodplain oak groves and black alder forests. The waterway will have a direct impact on 12 internationally important wildlife reserves that protect a number of rare species. BirdLife estimates that three-quarters of the world’s aquatic warblers are threatened by the construction of E40.

The Mid Pripyat Reserve covers 120km of the river and is designed to protect the largest area of natural river floodplain in Europe. Along this stretch alone, 182 bird species have been recorded, many of which are rapidly losing habitats elsewhere.

One town within the reserve, Turov, has stood on the site for 1,000 years. The name is believed to originate from tur, the Slavic word for the aurochs, an ancestor of the cow which once would have been common here. These towns are the “bloodlands” of Europe where some of the worst crimes of the 20th century took place, including early Nazi pogroms. In Turov, 500 Jewish people were executed by the Nazis. Today it is home to about 3,000 people, has an ageing population and limited opportunities for the young. Like many towns in Belarus, it has kept Lenin-related street names, statues of Lenin and Soviet murals.

It is also one of Europe’s most important sites for migratory birds, and just outside the town is a 144-hectare meadow managed by APB-BirdLife Belarus.

Over winter it looks like a large, unremarkable field where cattle are grazing. Networks of shrew tunnels and packs of stray dogs looking for trouble are the main signs of life. Volunteers regularly cut the scrub because wading birds like low grass as it allows nesting females to have a better view of potential danger.

In spring, the grassy island comes to life as it is swallowed up by the Pripyat. Globally threatened birds such as lesser white-fronted geese and black-tailed godwits flock here. More than 30 species of birds nest on Turov meadow, including half a million ruff, which have extraordinary mating rituals with some males disguising themselves as females to improve their chances of finding a partner. It has the highest breeding densities of northern lapwing and redshank in the world. There’s an annual party in the village to celebrate the arrival of spring migrants and Vintchevski says international birders are also starting to show an interest in the region.

Four hours’ drive downriver is the 190,000-hectare Pripyat National Park, nestled between the rivers Pripyat, Stviga and Ubort. It is visited by 256 bird species and contains rare alluvial oak forests unique to eastern Europe. The spring floods spread nutrients over the forest floor, making it particularly fertile. In winter the woods are still, but tracks in the snow show they are home to hares, wild boar and deer. It is completely silent except for the shrieks of siskin in the canopy.

Dr Helen Byron, the Save Polesia campaign coordinator at the FZS, explains that in spring the Pripyat floods in a similar way to the Amazon. “The rivers, the meanders and the marshes are all similar to those found in the Amazon. Its size and importance as a stopover for a large number of birds is widely unknown. There are no other places in Europe where creatures can have so much space, and yet because it was behind the iron curtain people just don’t know about it,” she says.

Climate change has already had an impact on the flooding, which means Polesia is becoming an increasingly fragile environment. Between 1955 and 1965, the river initially flooded in the first week of March but now it happens 16 days earlier. Fish are spawning between five and six days earlier. Winter floods are also becoming more frequent, with less flooding in spring, causing large areas of floodplain meadows, marshes, old lakes, wet oak and black alder forests to dry out.

Normally in January everything is frozen, but the last January snow fell in 2014, according to Vasil Blotski, who lives in the village of Verasnica with his wife Anastasia Blotskaja, head of Zhytkavichy APB-BirdLife Belarus branch. For Blotski, the river is a good place to take his two children fishing (they once caught a two-metre long catfish). He points out marks on the reeds that show the water level is more than two metres lower than it should be for this time of year.

Today he’s caught a small perch, bream and roach in the space of 15 minutes which he’ll cook for supper. He passes around chocolates and raw pig fat as he guts the fish. An eagle owl can be heard hooting in the background. “I’m worried that my children will no longer be able to enjoy this,” he says. “The beauty of this local nature reserve is that it’s unspoilt. It would be absolutely terrible if the E40 went ahead as I’m afraid we’re going to lose this river and it will just become a channel for ships.”

In addition to implications for Polesia, these wetlands are an important carbon sink, with 2,000 square kilometres of valuable carbon-sequestering peatland. According to FZS, if 50% of peatlands in Polesia turned to forest and 50% to grassland, it would release the same amount of carbon dioxide as one to two million extra cars on UK roads every year.

The effects of radiation

Further downstream, the Pripyat glides into the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Despite being the “worst nuclear disaster in history”, the official death toll is 54. Researchers believe the actual number could be as high as 200,000. Sizeable amounts of radioactive contamination fell far from the exclusion zone and thousands of deaths have not been properly investigated.

Polesia experienced a spike in cancers and birth defects following the disaster – the “Belarusian necklace” refers to the horizontal scar after surgery for thyroid cancer. Some estimates suggest one in five people in Belarus still live on contaminated land. Poor people have the greatest exposure to radiation because they eat locally sourced food such as wild mushrooms, berries and milk.

However, for many people life carries on as normal. “Because radiation is invisible no one was scared of it. I went to the 1 May parades after the explosion and had no idea it had happened. We still have very little information – the only bits I get are from the TV,” says Siarhei Stasienok, 65, a retired policeman who lives with his sister Tatiana, 64, in Kalinichy, just outside the exclusion zone.

“I was happy with Chernobyl and it would have been nice if it had exploded 10 or 20 years earlier. Everything was polluted after the explosion and money was put into the village to get better roads and clean water. We got new fences and there was generally a lot of investment in the village.”

Stasienok has a 3D portrait of Lenin on the outside his house. Inside, doilies cover the windows and an old-fashioned rotary dial telephone sits on the windowsill. There is still no running water.

Before Chernobyl there were 100 people living in Kalinichy, now there are 10. “People have been dying in this village but not until a few years after the explosion. We don’t know if they were killed by the radiation because doctors are not allowed to officially put cancer on death certificates,” he says. When someone dies their house is destroyed to prevent others moving in.

Stasienok had heard about the E40 plans but didn’t know much more than that. “I only believe things I can see,” he says.

Down the road from Stasienok’s house is the village of Smalehau, which had such high levels of radiation the entire place was wrapped in plastic and buried. Only the road down the middle and the graveyard at one end remain. Former residents are only allowed to return in a coffin.

Soviet experts have long maintained there is no need to further study the effects of radiation in this area, but many international scientists say we still know very little about it. Prof Wladimir Wertelecki, of the University of South Alabama, who has been studying birth defects in northern Polesia since 2000, says: “It is fundamental to study the rivers. Nothing is known without that. Dredging will stir up nucleoids that have been concentrated in the silt for decades. Radiation is not only airborne, rainborne and windborne but also waterborne.”

Kate Brown, a specialist in nuclear history from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and author of Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future, describes Polesia as a “layered toxic landscape”. She agrees there are likely to be high levels of radiation at the bottom of the river. “Part of the reason radioactivity in that region keeps getting suspended is because it’s a floody, swampy terrain. That was a wonderful ecological system in the past because it fertilised the pasture every year. Now what it does is that it re-suspends radioactivity in the soils,” she says.

The International Atomic Energy Agency has recommended that the Kyiv reservoir remains undisturbed.

Brown adds: “The zone of exclusion should stay a zone of exclusion as it was designed. We have such impatience; these are long-lived contaminants, but we want everything to decay on a normal biological timescale.”

What next?

Despite these concerns, discussions around E40 have been going on since 2013 and are now gaining momentum. Ukrainian and Belarusian government officials have agreed to start dredging the Dnieper and Pripyat rivers.

Speaking at a press conference in Minsk last September, the Belarus president, Alexander Lukashenko, said the Dnieper-Pripyat waterway could become an important part of the E40, which would essentially give Belarus access to the Black Sea. In Kyiv in the same month, Ukraine’s prime minister, Oleksiy Honcharuk, said the project was “absolutely real” and ready to be implemented. Ten million UAH (GBP315,000) has been allocated to dredge 64.5km of the Pripyat river in Ukraine, according to the minister of infrastructure, Vladislav Krikli.

Official documents suggest the Polish government has requested investment through China’s “belt and road” initiative, although it is not known if it has been granted.

The waterway will have a direct impact on more than 70 wildlife reserves. In Poland, the waterway will pass through Natura 2000 sites, which are protected under EU law. As a result, the feasibility study suggests a canal should be built adjacent to the river Bug; this is the most expensive part of the project. However, such attempts at mitigation are not afforded to reserves in Belarus and Ukraine.

“For me the E40 project is similar to a project on turning northern rivers to southern deserts: dividends to a small group of developers and builders and irreversible consequences for the wildlife in Polesia will take place. Some of the local inhabitants will get jobs at the E40 but most will suffer from the artificial changes in the region’s ecosystems,” says Vintchevski.

The EU provided EUR500,000 sponsorship for the 2015 feasibility study but refused to finance the project further due to concerns about mounting economic, social and environmental costs. Matti Maasikas, head of the EU delegation to Ukraine, wrote a damning report published in September 2019 saying the project violated both national legislation and international treaties.

Maasikas said the waterway would have “devastating consequences” for ecosystems in all three countries and would result in a “critical loss of biodiversity”. Economically, he said, the project (with an estimated cost of more than EUR12bn) was “unsound” and posed a serious threat of secondary radioactive pollution. He also criticised the feasibility study for ignoring the issue of climate change, which makes the construction of new waterways “unjustified and uneconomical”, especially given the E40 would need to be at least 2.5 metres deep along its entire route.

Without EU financing Poland, Ukraine and Belarus are now looking to implement the project in individual sections. Maasikas raised concerns that fragments of E40 infrastructure were being developed “as if the project was already approved by all interested parties and supported by the public”.

When APB-BirdLife conservationists requested a meeting with the Belarusian ministry of transport and communications to discuss the environmental implications of the E40, deputy minister Natalia Alexandrovich said there was nothing to discuss because no decisions had been made.

Przemyslaw Daca, the head of the Polish State Water Enterprise, says that the E40 would be a “pro-environment” development. “Waterborne transport is environmentally friendly, reduces CO2 emissions and other gases and particulates in the air. It also reduces noise emissions, the number of vehicles on roads and thus the number of road accidents.” Ministers in Ukraine and Belarus declined the Guardian’s request for comment.

Ivan Shchadranok, director of a sustainable development NGO Interakcia Foundation, which has lobbied for the E40 since the beginning, acknowledged that there has not been an adequate survey of the environmental implications of the project. However, he does not think the impact of the waterway would be as dramatic as some environment NGOs seem to think. “As a member of the cross-border commission I always tried to involve environmentalists in the creation of the feasibility study … Environmentalists are against such a study as they consider it as the first step to approval of the E40 restoration. So the situation is quite complicated,” he says.

Shchadranok believes there should be scientific research on the waterway before dredging starts but he thinks this is unlikely and environmental issues will continue to be overlooked. “Without a highly credible and accurate environmental assessment in place, environmental supporters have no leverage over those who are moving the E40 project forward now.”

Shchadranok says the issue of radioactive contamination is considered “quite serious by some water experts” but that he does not have the expertise to comment further.

Researchers from FZS are now rushing to help officials in Belarus and Ukraine have Polesia declared a Unesco world heritage site on account of its biodiversity. They believe it is in the same league as Yellowstone or Serengeti national parks.

“Nobody cared about protecting the Pripyat until someone outside the country said it was important,” says Vintchevski, who is working with FZS to get the project stopped. “We have been living next to something extraordinary without even noticing. Polesia is special, but few people saw it like that and now it could be too late.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features