Since the 1980s, fossil fuel firms have run ads touting climate denial messages – many of which they’d now like us to forget. Here’s our visual guide

Why is meaningful action to avert the climate crisis proving so difficult? It is, at least in part, because of ads.

The fossil fuel industry has perpetrated a multi-decade, multibillion dollar disinformation, propaganda and lobbying campaign to delay climate action by confusing the public and policymakers about the climate crisis and its solutions. This has involved a remarkable array of advertisements – with headlines ranging from “Lies they tell our children” to “Oil pumps life” – seeking to convince the public that the climate crisis is not real, not human-made, not serious and not solvable. The campaign continues to this day.

As recently as last month, six big oil CEOs were summoned to US Congress to answer for the industry’s history of discrediting climate science – yet they lied under oath about it. In other words, the fossil fuel industry is now misleading the public about its history of misleading the public.

We are experts in the history of climate disinformation, and we want to set the record straight. So here, in black and white (and color), is a selection of big oil’s thousands of deceptive climate ads from 1984 to 2021. This isn’t an exhaustive analysis, of which we have published several, but a brief, illustrated history – like the ‘sizzle reels’ that creatives use to highlight their best work – of the 30-plus year evolution of fossil fuel industry propaganda. This is big oil’s PR sizzle reel.

Early days: Learning to spin

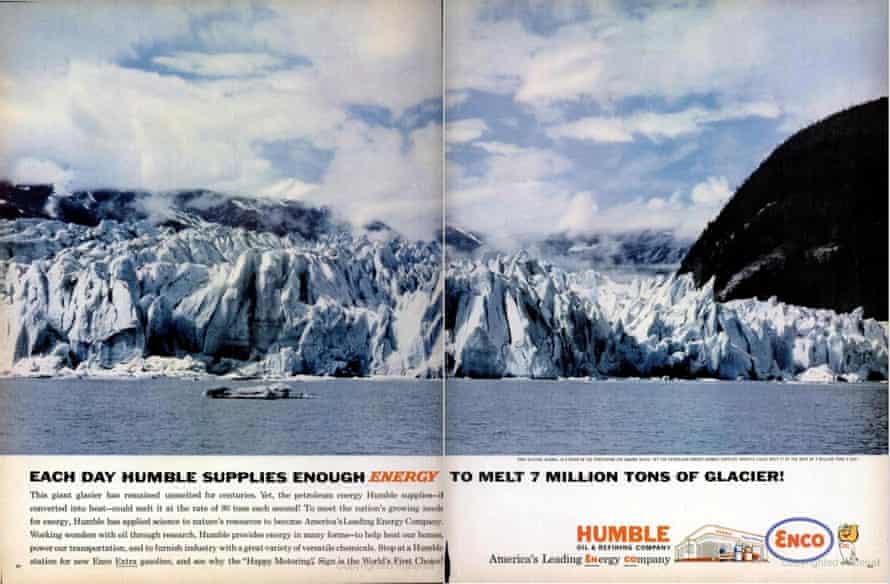

Humble Oil (now ExxonMobil) was not self-conscious about the potential environmental impacts of its products in this 1962 advertisement touting “Each day Humble supplies enough energy to melt 7 million tons of glacier!”

The truth behind the ad: Three years earlier, in 1959, America’s oil bosses had been warned that burning fossil fuels could lead to global heating “sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York”.

Their knowledge only grew. A 1979 internal Exxon study warned of “dramatic environmental effects” before 2050. “By the late 1970s”, a former Exxon scientist recently recalled, “global warming was no longer speculative”.

“Reposition global warming as theory (not fact)”

In 1991, Informed Citizens for the Environment, a front group of coal and utility companies announced that “Doomsday is cancelled” and asked, “Who told you the earth was warming … Chicken Little?” They complained about “weak” evidence, “non-existent” proof, inaccurate climate models and asserted that the physics was “open to debate”.

The truth behind the ads: Instead of warning the public about global heating or taking action, fossil fuel companies stayed silent as long as they could. In the late 1980s, however, the world woke up to the climate crisis, marking what Exxon called a “critical event”. The fossil fuel industry’s PR apparatus swung into action, implementing a strategy straight out of big tobacco’s playbook: to weaponize science against itself.

A 1991 memo by Informed Citizens for the Environment made that strategy explicit: “Reposition global warming as theory (not fact).”

“Emphasize the uncertainty”

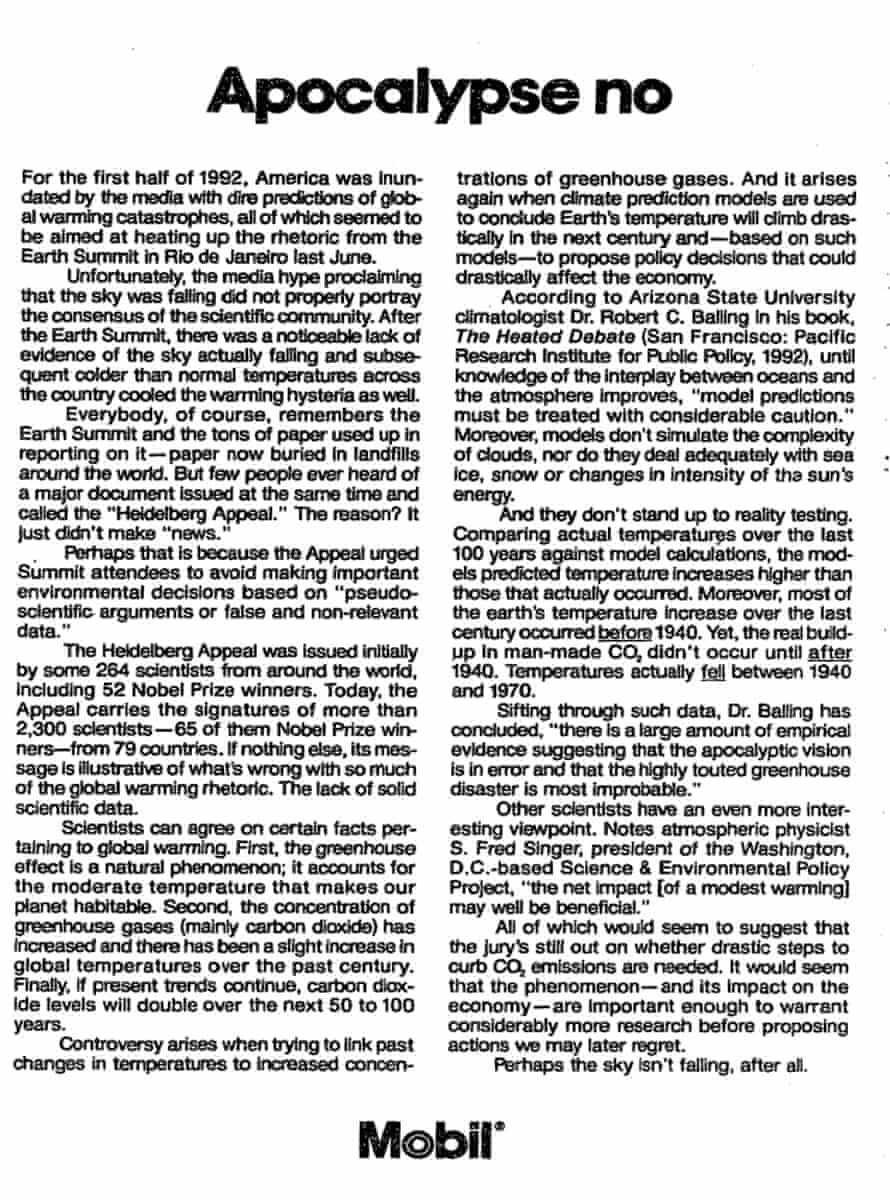

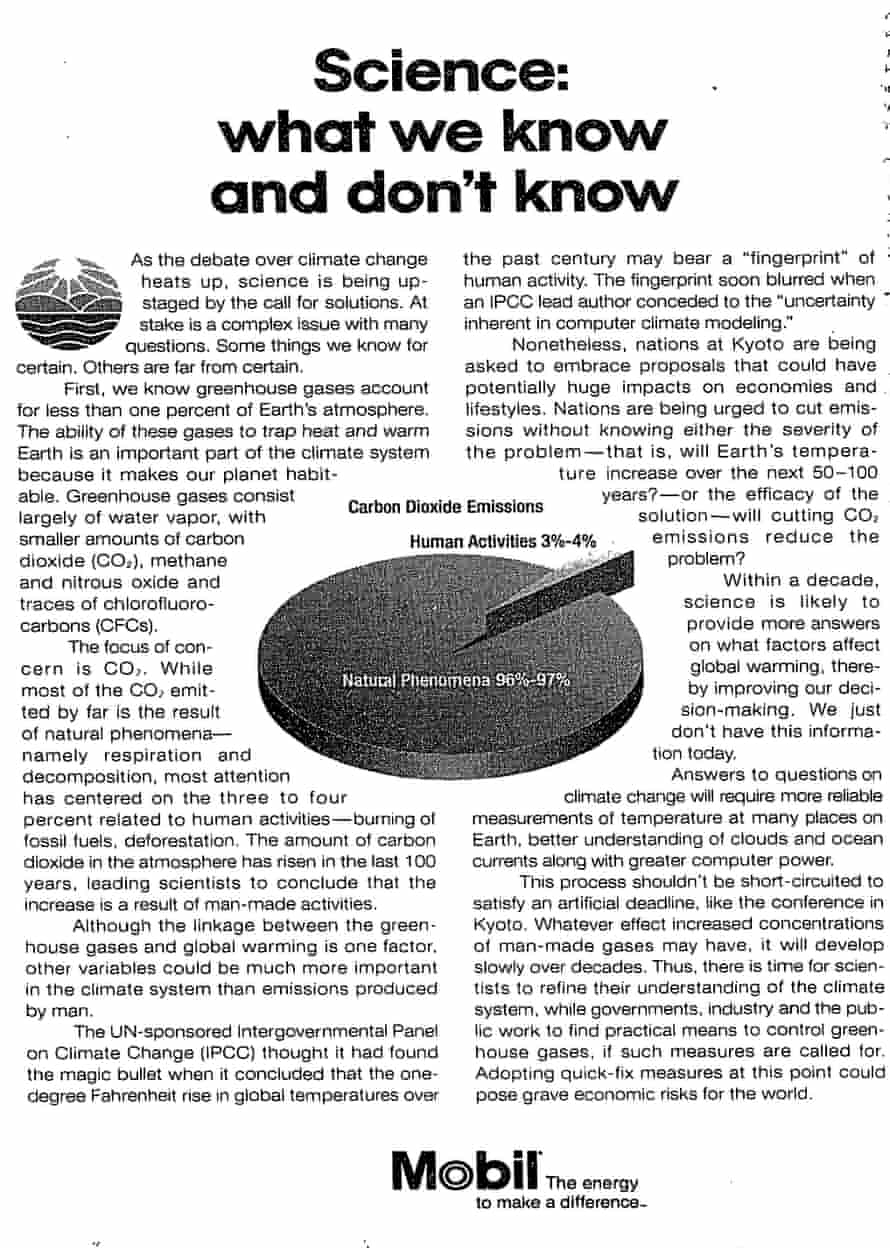

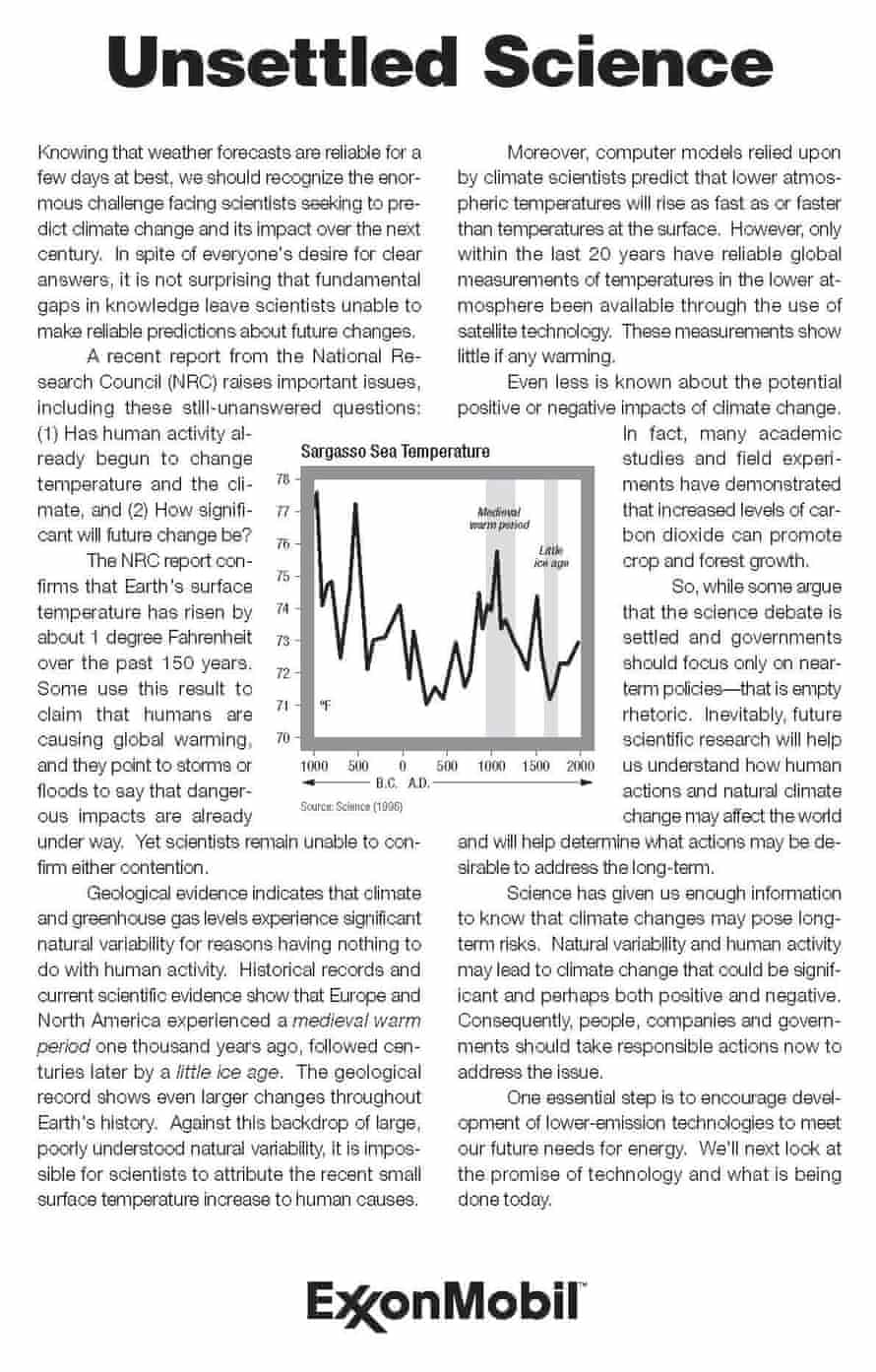

Mobil and ExxonMobil ran one of the most comprehensive climate denial campaigns of all time, with a foray in the 1980s, a blitz in the 1990s and continued messaging through the late 2000s. Their climate ‘advertorials’ – advertisements disguised as editorials – appeared in the op-ed page of the New York Times and other newspapers and were part of what scholars have called “the longest, regular (weekly) use of media to influence public and elite opinion in contemporary America”.

Between 1996 and 1998, for instance, Mobil ran 12 advertorials timed with the 1997 UN Kyoto negotiations that questioned whether the climate crisis is real and human-made and 10 that downplayed its seriousness. “Reset the alarm,” one ad suggested. “Let’s not rush to a decision at Kyoto … We still don’t know what role man-made greenhouse gases might play in warming the planet.”

The truth behind the ads: “Exxon’s position”, instructed internal strategy memos from 1988-89, was to “extend the science” and “emphasize the uncertainty in scientific conclusions” about the climate crisis. Or as a 1998 “Action Plan” by Exxon, Chevron, API, utilities companies and others declared: “Victory will be achieved when average citizens” and the “media ‘understands’ (recognizes) uncertainties in climate science.”

ExxonMobil continued to fund climate denial through at least 2018. One of their 2004 advertorials claimed “scientific uncertainties” precluded “determinations regarding the human role in recent climate change”. That was untrue. Nine years earlier, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had concluded a “discernible human influence on global climate”. ExxonMobil’s chief climate scientist was a contributing author to the report.

Economic scaremongering

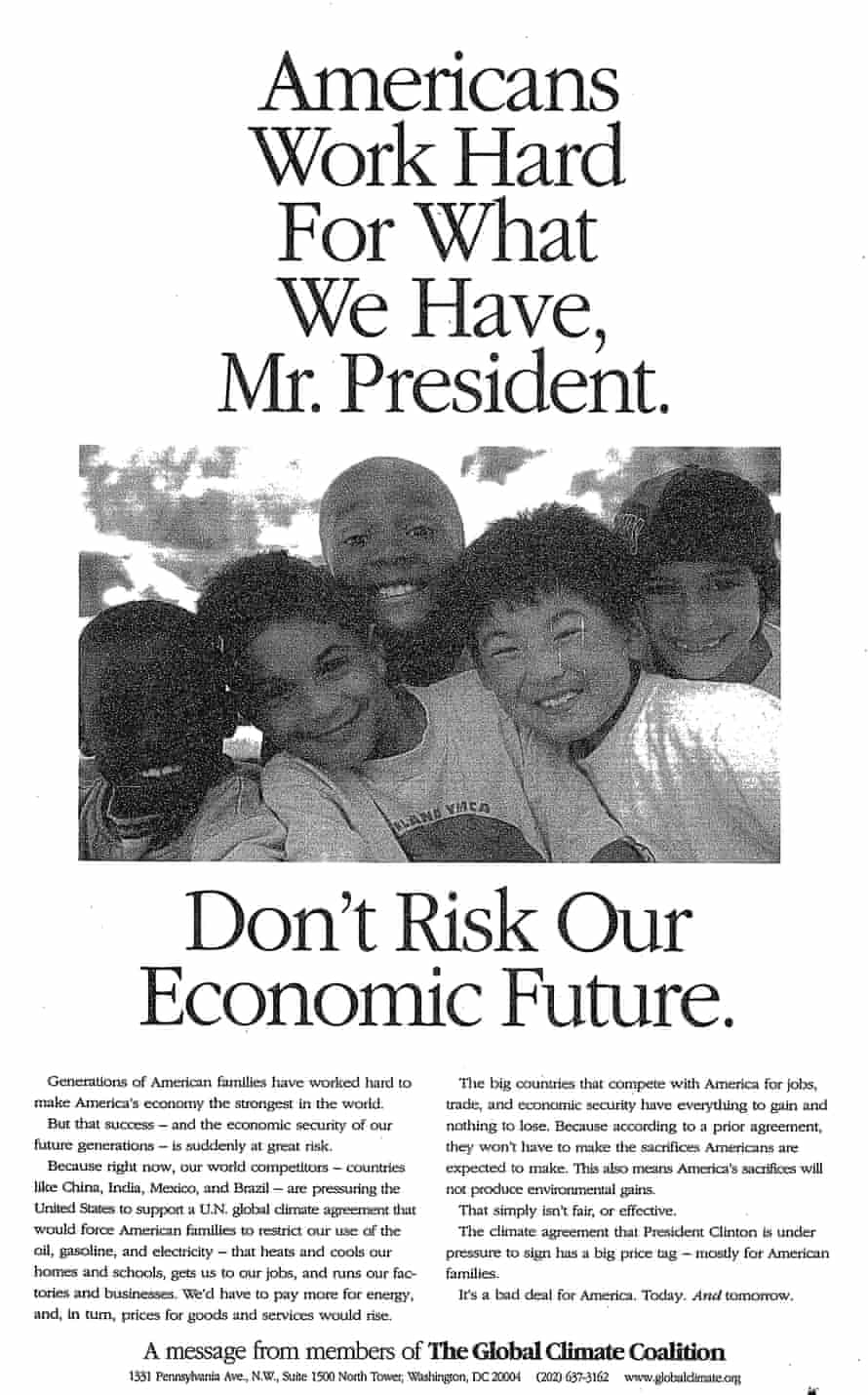

“Don’t risk our economic future,” implored the Global Climate Coalition, a front group for utility, oil, coal, mining, railroad and car companies. This 1997 ad also targeted the Kyoto negotiations and was part of a $13m campaign that was so successful that the White House told GCC: President Bush “rejected Kyoto, in part, based on input from you”.

The truth behind the ad: Put “emphasis on costs/political realities”, instructed a 1989 Exxon strategy memo. Just as the fossil fuel industry funded contrarian scientists to deny climate science, it also touted the flawed economic analyses of industry-funded economists.

The best predictors of fossil fuel industry ad spending are media scrutiny and political activity. Today, economic scaremongering has gone digital, with huge spikes in television and social media ad spending by oil lobbies each time climate regulations loom. In the run-up to the 2018-20 US midterm and presidential elections, ExxonMobil spent more on political advertising on Facebook and Instagram than any other company in the world (except Facebook itself).

It’s not our fault, it’s yours

From 2004-06, a $100m-plus per year BP marketing campaign “introduced the idea of a ‘carbon footprint’ before it was a common buzzword”, according to the PR agent in charge of the campaign. The targets of this campaign were the “routine human activities” and “lifestyle choices” of “individuals” and the “average American household”. In 2019, BP ran a new “Know your carbon footprint” campaign on social media.

The truth behind the ads: Big oil’s rhetoric has evolved from outright denial to more subtle forms of propaganda, including shifting responsibility away from companies and on to consumers. This mimics big tobacco’s effort to combat criticism and defend against litigation and regulation by “casting itself as a kind of neutral innocent, buffeted by the forces of consumer demand”.

Greenwashing: talk clean, act dirty

“We’re partnering with major universities to develop the next generation of biofuels,” said Chevron in 2007. This is also a top talking point of BP, ExxonMobil and others.

ExxonMobil has been trumpeting its research into algae biofuels for more than a decade – from black-and-white print ads (2009) to digital commercials (2018-21).

The truth behind the ads: Greenwashing confers companies with an aura of environmental credibility while distracting from their anti-science, anti-clean energy disinformation, lobbying and investments. The goal is to defend what BP calls a company’s “social license to operate”.

One way fossil fuel companies give themselves a green sheen is to establish – then boast about – what a 1998 API strategy memo termed “cooperative relationships” with reputable academic institutions. Big oil’s colonization of academia is pervasive. Shell’s ongoing sponsorship of the London Science Museum’s climate exhibition comes with a gagging clause prohibiting the museum from discrediting the company’s reputation.

As for algae: America’s five largest oil and gas companies spent $3.6bn on corporate reputation advertising between 1986 and 2015. ExxonMobil has spent more on advertising than on algae research.

“We’re part of the solution!”

BP “developed an ‘all of the above’ strategy” for marketing energy from 2006-08, “before any presidential candidates spoke of the same”, according to BP’s PR lead.

Big oil continues to push this narrative of ‘fossil fuel solution-ism’, including its “all of the above” language on social media, in Congress and in paid-for, pretend editorials in the Washington Post. To make this spin stick, fossil fuel companies have been calling methane “clean” since at least the 1980s. “Natural gas is already clean,” said API Facebook ads and billboards last year.

The truth behind the ads: In contradiction to the science of stopping global heating, big oil asserts that fossil fuels will be essential for the foreseeable future. The “all of the above” energy mantra was – as BP’s advertising creative put it – “co-opted by politicians in 2008” and became a centerpiece of the Obama administration’s energy policies. The campaign also positioned methane as a “clean bridge” fuel.

Like “clean coal”, calling methane “clean”, “cleanest” or “low-carbon” has been deemed false advertising by regulators.

Distorting reality in the 2020s and beyond

A Shell TV ad last year featured birds in the sky, fields of wind and solar farms, the CEO of a Shell renewables subsidiary saying she’s “made the future far cleaner and far better for our children”, and not one reference to fossil fuels.

The truth behind the ad: Between 2010 and 2018, 98.7% of Shell’s investments were in oil and gas. Such misrepresentations are industry-wide.

Today, we’re all inundated with ads that leverage a combination of narratives, including those illustrated above, to present fossil fuel companies as climate saviors. It’s way past time we called their bluff.

The narratives highlighted here are a selection of ‘discourses of climate denial and delay’ previously identified by the authors and other researchers. The advertisements selected to illustrate these discourses were identified by the authors based on a review of dozens of peer-reviewed studies, journalistic investigations, white papers, ad libraries, newspaper archives, social media reports and lawsuits.