The stress on the food system caused by the pandemic gave the Stewarts an idea: creating a commercial ranch in Arizona

On the eastern edge of the Sonoran desert, in the grasslands not ten miles north of the US-Mexico border, James and Rachael Stewart have arranged a dozen weight lifting machines and dumbbell sets.

At sundown, as they and their four children herd lambs and alpacas into their stalls, the occasional chick or duck passes between these markers of the Stewarts’ previous life.

Two years ago, James and Rachael were fitness trainers living in a Phoenix suburb.

James traveled frequently to bodybuilding competitions across the south-west, in cities such as Tucson and Albuquerque, and Rachael had just completed a master’s degree in business management. But then the Covid-19 pandemic struck, shutting down meatpacking plants across the country, and they found themselves without the protein sources they needed as athletes – and parents of four growing children.

That’s when an idea came to them that sounded a little impossible at first, but felt more important the more they thought about what doing it would mean for their kids. James sold his 1972 Chevy Caprice and the couple purchased 10 acres of land just outside of Douglas, Arizona. They were going to start one of Arizona’s very few Black-owned commercial ranches.

In October of 2020, James and Rachael Stewart broke ground on the ranch they are calling the Southwest Black Ranchers. As a biracial couple (James is Black and Rachael is Filipina and Mexican), they immediately began looking for other Black ranchers for guidance – and so far have struggled to connect with any in Arizona. According to the USDA, Black farmers make up less than 1.5% of the country’s producers and are primarily located in southern and mid-Atlantic states, despite the long, but often forgotten, history of Black ranchers in the American west. Connecting with other Black farmers, ranchers and gardeners across the country through social media, the Stewarts hope to build a ranch that inspires their children and other new generations of Black farmers to return to the south-west.

In 1920, Black farmers made up 14% of the industry, but after thousands lost their land due to discriminatory lending practices at the US Department of Agriculture, less than 2% remained. In order to connect with other Black farmers, the Stewarts joined a Facebook group where they met Texans who taught them about hydroponics and a South African farmer whose work on regenerative agriculture is inspiring their goals for the ranch. At home in Arizona, they also connected with Drinking Gourd Farms, a network of Black gardeners and homesteaders in Phoenix, who are helping the Stewarts mulch their farm’s soil. As the Stewarts prepare their ranch they’re hoping to create a world where their children don’t think twice about being part of a Black-led agricultural revolution.

When James and Rachael first bought their land outside of Douglas, they were motivated by the inequities they had seen come to light during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic. Tyson Foods had just shut down several of its meatpacking plants and published a full-page New York Times ad warning that “the food supply chain is breaking”. That same week, the USDA reported that beef production was down 25% and grocery stores started rationing the amount of meat each customer could purchase. That’s when James and Rachael realized the perils of a factory farming system, where the fate of one company could impact their ability to feed their four children. They wondered if they’d have more control if they owned their own livestock – and if the food supply chain overall might be more sustainable if there were many local farms, meatpackers and processors, as opposed to just a few.

Although those questions have continued to motivate them, James and Rachael say it’s their children – who go by their nicknames J5, Nay, Zey and JG – that are the real driving force behind their work.

“We live in a very white state,” said Rachael, and many people “don’t realize the societal impact of [Black] kids not seeing positive role models who look like them.” Arizona’s population is only about 5% Black, and nearly 83% white. When the Stewarts discovered that they’d be nearly the only Black ranchers in Arizona, they decided they wanted to fill that gap for their kids.

“Sometimes you need to actually see something before it can become tangible,” said Rachael. “You need to see a Black farmer before you realize you could be a Black farmer.”

James and Rachael see their work as parents not just as role models, but also as the creators of new systems that they can pass down to their children. “We want to create a situation where our kids have an option, and they have a trade,” so that if they “don’t want to take on the debt” of college “that doesn’t hinder them from being successful”, says James. Although he and his wife both have college degrees, they’d like their children to have choices so they don’t “have to go $80,000 into debt to get a $35,000 job”.

We’re trying to “create an alternative system for minority and socially disadvantaged ranchers”, says Rachael, so that we can hand over a business to our children “that is always going to be needed”. Part of that work has involved creating alternative networks with other Black ranchers, farmers, gardeners and entrepreneurs.

The Stewarts realize they have a long way to go to make their ranch financially viable for the long term. Although they were able to purchase their initial animals and supplies with the support of a Go Fund Me account, they are now Beta testing approaches to sales, meeting with meat processors, and also applying for grants, including ones from the USDA.

One of those first collaborations was with the Drinking Gourd Farms community in Phoenix, which is primarily led by Black Muslim refugee women. During the early months of the pandemic, Drinking Gourd Farms also began to reevaluate the sustainability of the food supply chain. To make sure Black families had access to healthy food while that system was in turmoil, they distributed food boxes to 4,600 families across the state. When a few of Drinking Gourd Farms’ members heard about the Stewarts’ plans, they drove down to visit the family in Douglas. That’s how James and Rachael met their ranch manager Grand Rahba.

Rahba had spent most of the past decade working at independent farms and gardens across the country, learning sustainable techniques such as composting and permaculture, before landing at Drinking Gourd Farms.

On those farms, Rahba says he learned the techniques to “set up an ecosystem that will sustain itself” and the “importance of having access to stuff, being able to grow your own food, raise animals, have space.”

When he met the Stewarts, he was immediately drawn to their mission and bought his own five acres of land adjacent to theirs. For Rahba, Southwest Black Ranchers was an opportunity to prioritize alternatives to capitalism, that would allow him, the Stewarts and other Black farmers to reconnect with the land and their livestock, while reimagining their relationship to work and rest.

A history of pioneering Black cowboys

It’s late morning on the Stewart’s ranch and Romeo, their sole male alpaca, has gotten loose. He’s supposed to be in his pen while the females graze, but he’s wily and desperate to mate, so instead he’s chasing Soleil – who seems decidedly uninterested in his affections. The pair are not two feet away from crashing into their pen’s fencing when 12-year-old J5 lassos Romeo in one fell swoop – accomplishing a skill he and his siblings have been practicing for months.

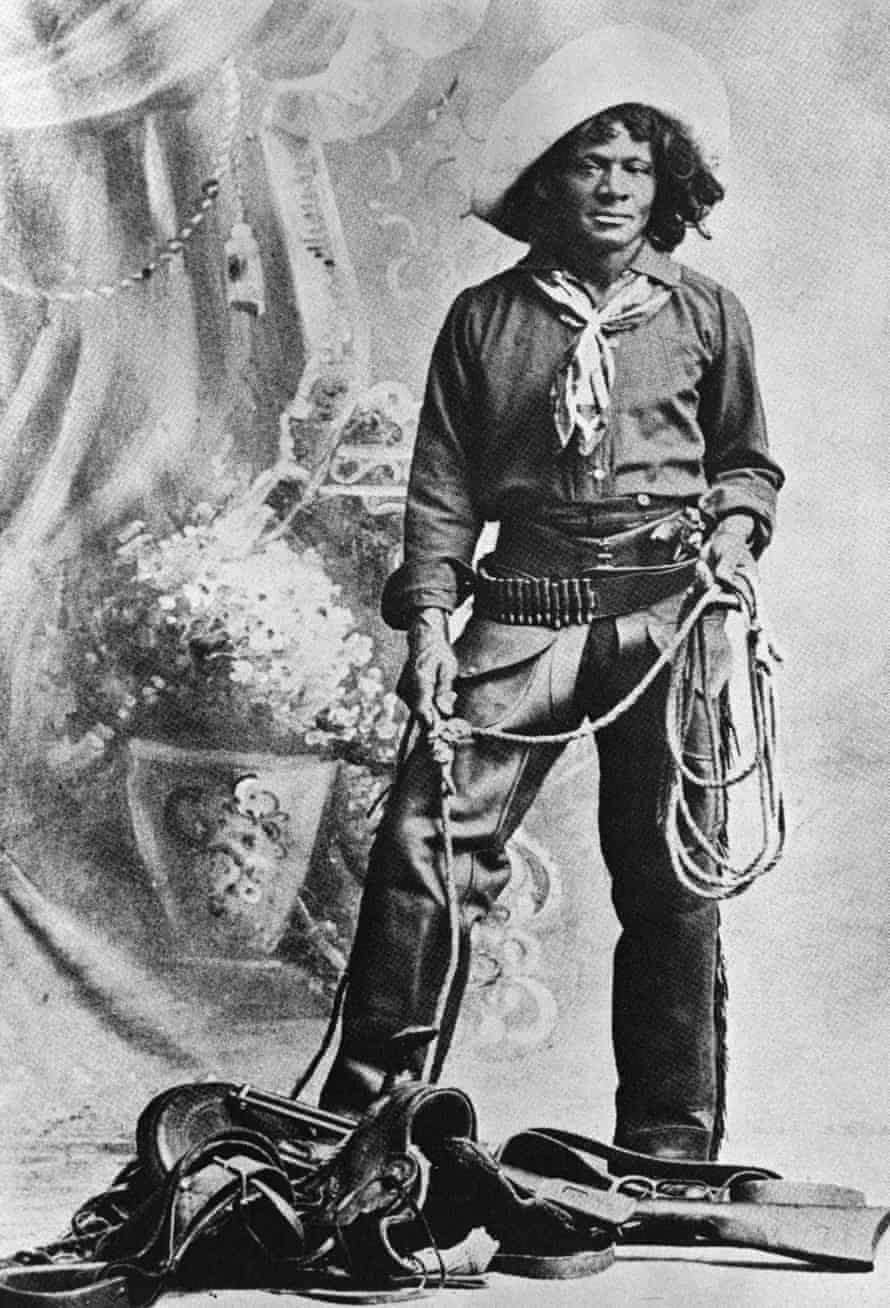

Zey, Nay and JG cheer for their brother as he shepherds Romeo into his stall, and then each takes their own turn trying to lasso the alpaca under J5’s now expert guidance. What none of them realize in the moment is that J5 has mastered a skill that Black ranchers invented and perfected generations before him.

“It was enslaved cowboys of African descent in Mexico who invented this new technique of capturing cattle” with a lasso, says Andrew Sluyter, professor at Louisiana State University and author of Black Ranching Frontiers: African Cattle Herders of the Atlantic World, 1500-1900. “The previous way of capturing cattle was simply to ride behind them with a lance that had a sharp blade on the end of it” and cut the tendons in the cow’s rear legs. But then, in the 17th century, there was “a change in the laws that makes it illegal in New Spain and what’s now Mexico for cowboys who are slaves … to own one of those lances with that halfmoon-shaped blade on the end of it because there were more and more slave rebellions.”

That’s when enslaved cowboys developed the idea of lassoing cattle.

“There was this imperative for Black cowboys to advance some kind of alternative means to capture cattle that didn’t involve a weapon,” said Sluyter, who cites an engraving from 1643 of Black cowboys demonstrating the technique by using a long pole to drop a lasso over a cow. “By the 1700s it had been perfected so they no longer needed that pole.”

Although lassos and cowboy hats are typically associated with white cowboys in the American west, Sluyter says it shouldn’t come as a surprise that many early ranching techniques were developed by people of African descent.

“If you look at the world in 1492 when Columbus lands in the Caribbean, the largest single area of open range cattle ranching was the Sahel” in Africa, he says. “That’s where cattle and humans evolved together over millions of years” and “that’s where the expertise was”.

The word “cowboy” itself originated during slavery when ranchers called Black cow hands by the pejorative “cow boy”. During reconstruction, many formerly enslaved men took jobs as ranch hands and by the late 1800s, historians estimated that one in four cowboys working on the frontier were Black. One of those men was Nat Love, who earned the nickname “Deadwood Dick” in a roping competition in 1876. Another was Bass Reeves, the first Black deputy US marshal west of the Mississippi River – and allegedly the inspiration for the Lone Ranger.

Today, the legacy of Black cowboys is continued by groups such as the Louisiana Trail Riders and the Compton Cowboys. For more than a decade, the Arizona Black Rodeo Association has held a rodeo in Phoenix each year. And Black cowboy Lu Vason has, since 1984, hosted the traveling Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo, named after the Black cowboy who invented rodeo steer wrestling (or bulldogging). But to this day, few Black cowboys or ranchers actually own their own land or livestock.

Finding a home on the land

If you ask James and Rachael for their address, they’ll send you GPS coordinates instead. Although their ranch isn’t far outside of Douglas, their neighbors are few and far between – depending on the route you take, you might see the “No Trespassing” signs along a neighbor’s fence, but then again you might only spot the distant mountains and mesquite trees. Despite the many neighboring farms, the Stewarts are actually located in a food desert: the only grocery store for miles north of the border is a WalMart.

“There’s a fear of being out on the land, and being rural, and being the only minority there. It’s a valid fear,” said Rachael. Moving out of the city, she and James say, has been precarious.

“If you’re coming out here with money obviously everything’s different, but if you’re not coming out here with money then there’s a lot of change you’ve got to get ready to deal with. It’s not the easiest experience in the world,” says James. But if you do come out on the land, “you’re getting a lot more freedom”.

Since moving, James and Rachael have helped three other Black families buy land on their same street. They’re still wary of harassment, but they’ve started building their own networks – largely made up of people they’ve met on social media, like a South African farmer whose work on regenerative agriculture is inspiring their goals for the ranch and Black ranchers in Texas who’ve taught them about hydroponics.

Black farmers “are already doing these things independently because they’ve been forced to”, says Rachael. For generations, official structures, such as the USDA, did not support Black farmers equally, so those farmers created their own systems. But the result, Rachael says, is that those independent networks exist now for ranchers who hope to challenge the factory farming system.

The Stewarts have built almost everything on their ranch from scratch. They’ve traded their labor for supplies, built pens out of pallets and wire fencing, and even adopted rehomed animals to grow their flock. “We’ve never bought anything new. Everything we’ve ever had was used,” says Rachael. That reality can be difficult, she says, “sometimes you get to this point where you think you don’t deserve anything”, it’s a mindset that “minorities just always get the leftovers”.

But despite – or rather because of – that, Rachael says, she and James “are trying to create a blueprint for people to follow”. Including their kids. “Whatever we learn, we want to be able to pass on.”