‘Volcanoes are life’: how the ocean is enriched by eruptions devastating on land

Lava is destroying much of La Palma but the last eruption in the Canaries appears to have ‘fertilised’ the surrounding seas

Last modified on Tue 5 Oct 2021 02.28 EDT

The eruption of the volcano on La Palma in the Canary Islands is a vivid reminder of the destructive power of nature but, as it lays waste all before it on land, for marine life it is likely to be a blessing.

When the lava reached the sea near the La Palma marine reserve on Tuesday night, every marine organism that was unable to swim out of danger was instantly killed. However, unlike on land, which lava renders lifeless for decades (and with forest not returning for more than a century), marine life returns quickly and in better shape, research shows.

A study by researchers at the Spanish Institute of Oceanography and the University of Las Palmas in Gran Canaria looked at the after-effects of Tagoro, a volcano that erupted underwater just off the nearby island of El Hierro in 2011.

The eruption, which continued for nearly six months, caused such extreme changes in temperature, acidity and chemical composition of the water in the Mar de las Calmas marine reserve that all traces of life were wiped out in area popular for recreational diving.

However, the researchers found that within three years, with the exception of a 200-metre radius from the crater, the entire submarine volcano was covered with life, and not just basic life forms such as phytoplankton, but organisms from the surface of the ocean to the seabed, including mature fish, squid and octopus.

In fact, the biomass of phytoplankton was bigger than before the eruption. However, although there was more of it, there was a decrease in biodiversity.

“The lava is rich in iron, as well as magnesium and silicates, and this supplies nutrients to the water,” says Carolina Santana Gonzalez, an oceanographer at the University of Las Palmas in Gran Canaria.

“This happens almost immediately. The lava fertilises the water and the area recovers in a short space of time. In the case of El Hierro, it had almost completely recovered within three years.”

“It’s like a forest fire. It destroys everything, but at the same time provides nutrients for new growth. The difference is that marine life recovers much faster than a forest.”

In El Hierro, the concentration of iron near the volcano’s cone was nearly 30 times the normal level. The waters around the volcano were also rich in carbon dioxide, which lowers pH levels and thus helps microorganisms to absorb the iron.

Iron oxidises quickly in water and forms other compounds that sink to the seabed. However, as there continued to be low-level volcanic activity in El Hierro, it continued to emit iron.

Another factor is “upwelling”, which occurs when lava forces nutrient-rich water near the seabed to the surface.

In La Palma, the lava is abouty five miles (8km) from a marine reserve that covers about 3,500 hectares (8,500 acres) of sea. It is home to tropical anemones, sea bream, brown algae, lobsters and sea turtles.

“We can’t stop nature, but nature has mechanisms for regeneration that are rapid and effective,” says Eugenio Fraile Nuez, who is in charge of monitoring the La Palma volcano from the Institute of Oceanography’s vessel moored off the stretch of coast where the lava is pouring into the sea.

“That’s why it’s not an environmental catastrophe, but quite the opposite: volcanoes are life,” he says.

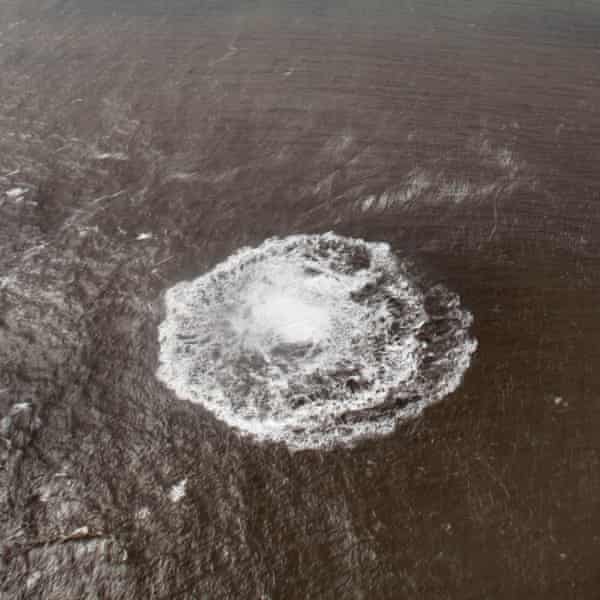

As eruptions continued, the lava advancing at two metres an hour and soon covered more than 20 hectares of sea to a depth of 24 metres, doubling the size of the island’s newly created peninsula.

While marine life may face a bright future once the volcano stabilises, on land the picture is grim. The lava has destroyed 855 buildings, rendered hundreds of hectares of land unusable and buried about 17 miles of road.

About 20% of banana plantations, key to the island’s economy, have been lost.

The scientists who spent six years studying the aftermath of the El Hierro eruption say that marine areas with volcanic activity could be used to understand how the climate crisis could affect oceans.

In the meantime, Santana says the biggest threat to the island’s marine life is not the volcano but human activity. “The real problem is overfishing,” she says.