Surging gas prices and fuel bills focus Tory minds on the nuclear option

Growing fears of energy security are leading a rethink on Chinese involvement in atomic plans. But what alternative are there?

Among the subjects preoccupying delegates at the Conservative party conference in Manchester on Monday, energy will be near the top of the list.

Soaring global gas prices, a lack of windpower and surging household bills have focused minds on Britain’s energy needs – and the role of nuclear power in particular.

For the past decade, Britain’s ambitions to build more nuclear power plants have been entwined with China’s. Hinkley Point C, the long-delayed and over-budget GBP23bn plant in Somerset that will be the first new power station in a generation, is being bankrolled with Chinese cash.

China’s nuclear ambitions – at least as far as Britain is concerned – may be about to collide with a new political reality. Opponents of Chinese involvement in UK infrastructure are turning cartwheels at reports that the government is planning to eject the People’s Republic from Sizewell C – a GBP20bn sister to Sizewell B on the Suffolk coast, which is intended to power 6m homes.

Beijing’s international nuclear ambitions have suffered a “body blow”, according to Iain Duncan Smith. The former Conservative party leader’s Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China campaigned, successfully, for the telecoms giant Huawei to be kicked out of the UK’s 5G network, after pressure from Donald Trump’s administration.

“The British government has learned the hard way that we’re going to have to stand up to them,” he said.

Tom Tugendhat, chair of the Sinosceptic China Research Group, hailed the “more realistic approach”. “Chinese state-owned companies shouldn’t be building nuclear power plants in Britain,” he said. “As the China Research Group has shown, Beijing’s attempts to interfere in other countries are growing and the UK should not make itself vulnerable.”

The duo were reacting to suggestions, first reported in the Guardian, that officials are examining methods by which China General Nuclear (CGN), which has a 20% stake in the Sizewell C project due to be built by France’s EDF, can be removed from the equation. An announcement could come as early as this month, with taxpayers’ cash used instead.

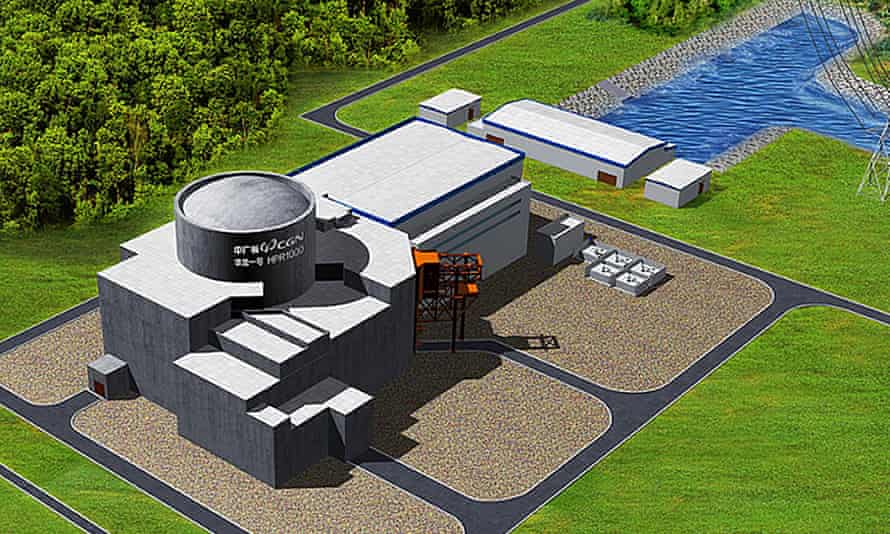

CGN was due to step up its involvement in British nuclear post-Sizewell, through a majority position in Bradwell B in Essex, intended to be a showcase for the Chinese-designed Hualong One (HPR1000) reactor.

If China is forced out of a minority financial position in a plant built by French state-backed EDF, the prospect of a Chinese-controlled facility a mere 40 miles from London is surely a non-starter.

Bradwell would have been a major coup, demonstrating to the world that a major economy such as the UK was open to Beijing’s proprietary nuclear technology.

Duncan Smith thinks the UK’s decision could scupper the plan. “If we do this, other countries will follow suit and it will turn out to be a very big decision indicating direction of travel with China. It’s a big strategic decision.”

He also has price on his side. It costs around twice as much to produce a kilowatt hour of nuclear power compared with offshore wind and solar power.

But have the anti-China hawks started celebrating too soon? One industry source, who has been observing China’s nuclear ambitions for years, sees no reason to believe that CGN will bow to pressure to withdraw. Forcing China out would create a diplomatic row. “There has been a sustained effort […] to make the atmosphere so hostile that the company will just give up and go away,” the source said. “That seems a really heroic assumption.”

CGN is deeply involved in the 3.2GW Hinkley project, which could yet run beyond its current GBP23bn budget and its 2027 completion date.

“Of course it [continued Chinese investment in Hinkley] could be at risk,” said the source. “CGN is making a big contribution [to the plant] but it’s not the big flagship ‘welcome to the world’ thing that building an HPR1000 would be.”

Pressure on the UK government from its own MPs, but also from abroad, seems to be behind the decision to keep China at arm’s length.

Opposition from the likes of Duncan Smith and Tugendhat is one thing but American intervention is quite another.

The former US secretary of state Mike Pompeo last year urged Britain to look across the Atlantic for its nuclear future, saying the US “stands ready to assist our friends in the UK with any needs they have”.

The Trump administration was vocally opposed to Chinese technology incursions into the west and the Biden administration is no different. But jilting China to please America leaves Britain facing a problem.

The UK nuclear fleet has a capacity of 8.9GW, about a sixth of peak demand in winter and 20% of our average needs annually.

More than 7GW of that capacity – seven out of the eight existing power stations – is due to for retirement between now and 2030.

Hinkley is the only project with a completion date in sight, with one reactor firing up in 2026 and the next in 2027 but it is an optimistic assumption that no delays will occur. Even if Hinkley proceeds as planned, UK nuclear capacity will still fall to 4.4GW by 2030 if nothing else is done.

The upcoming Cop26 climate conference in Glasgow has reminded everyone of the UK’s commitment to decarbonise the economy entirely by 2050, while the gas price crisis has underscored the risks of relying solely on fossil fuels and renewable energy. Big nuclear power plants and their spinning turbines provide the vital inertia that is required to balance the grid and keep its frequency stable.

The business secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, is keen to emphasise that nuclear is part of the solution but something needs to happen to speed up these multibillion-pound projects.

At Sizewell, the government’s great hope is regulated asset base (RAB) financing, an investment structure that offers potential investors safe returns but requires legislation.

A government spokesperson described it as a “credible model”, indicating moves are afoot to pursue that as a means of funding Sizewell – not to mention projects such as Wylfa, on Anglesey, which Japan’s Hitachi recently walked away from, citing funding concerns. The new financing model, used in water and power networks, could lure in American investors such as the construction giant Bechtel.

If Beijing and London can find a diplomatic solution to remove CGN from UK nuclear, this funding model is a solution that could attract backers to replace the Chinese. If nuclear has a major role to play in Britain’s decarbonised future, time is of the essence.

Nuclear options

The UK has struggled to get nuclear projects moving in the past decade but it does have options.

The first is to find investors for major new-build projects. While investors in Sizewell C are already lined up, China’s involvement is in doubt after signals that ministers are preparing to buy out its share of Bradwell B in Essex.

Offering more attractive funding options could be the key to kickstarting the GBP20bn Wylfa project on Anglesey after Hitachi walked away last year. But the UK’s National Infrastructure Commission is cool on large-scale nuclear new projects.

Advanced modular reactors (AMR), which use new coolants instead of water, are seen as a potential technological leap forward. Earlier this year, the government published a call for evidence about launching a programme to demonstrate their viability. However, even this pilot stage won’t be ready until the 2030s.

There is plenty of excitement about Rolls-Royce’s plans for small modular reactors (SMRs), dubbed mini-nukes that could, in theory, be rolled out quickly and easily to boost capacity. The British engineering giant thinks it could plug them into the grid by 2030.

Then there is the tantalising moonshot prospect of cracking nuclear fusion, harnessing the power of the stars to create, in theory, limitless energy.