‘Lightbulb moment’: the battery technology invented in a Brisbane garage that is going global

Dominic Spooner’s startup Vaulta is working on a reusable battery casing to create less waste and a lighter product

As some of the world’s largest companies invest billions to advance battery technology, Dominic Spooner has been working at solving the next problem: the impact of unwieldy – and environmentally unfriendly – battery casings.

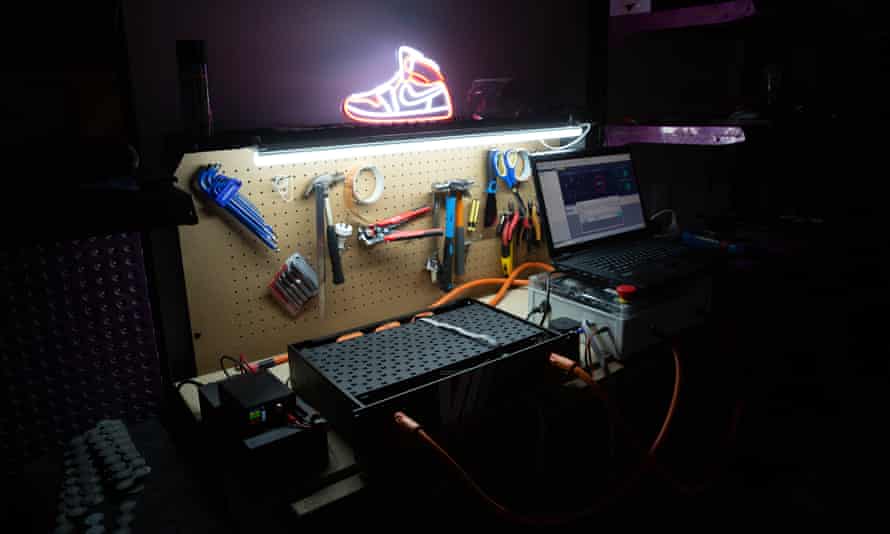

Spooner runs his lightweight battery casing technology firm Vaulta from a shared garage in Brisbane’s north. “Batteries will change our lives in ways that we’re maybe not even totally aware of, but … we can create our own new group of problems if we’re not careful,” he says.

From a workspace surrounded by packing boxes and other junk, like an old door, Spooner and his team have caught global attention.

This year Vaulta has signed agreements with aerospace and car battery companies, including one with Braille Battery – an American manufacturer of ultra-lightweight batteries for Nascar, IndyCar and the Australian Supercars.

Last month the company received a $297,500 federal grant to commercialise its technology.

For those still sceptical about the extent and pace of global innovation being directed towards battery technology, the International Energy Agency says patents for energy storage inventions have grown four times faster than the rest of the technology sector, and are set to catalyse clean energy transitions around the world.

In 2020, Samsung spent US$710m (A$950m) on research and development of next-generation electric vehicle (EV) batteries. An Israeli firm has this year begun production of an EV battery that can charge in five minutes.

‘We’ve got time now to do it right’

So how does a tiny garage-bound Brisbane startup find its place among global giants in the rush to innovate?

“It seems like almost every other day there are tech advancements – in the cells, cell types, cell shapes, cell geometry – coming out of the US or Europe,” Spooner says.

“But the way they’re being packaged, the way they’re being housed, was just being overlooked.”

Vaulta’s technology reduces the number of components used in battery cases. The casings reduce the battery size by about 18%. They also don’t weld parts together, which means they can be taken apart and reused rather than dumped – a start on preventing some of the 98% of disused batteries that goes into landfill.

Spooner says the “lightbulb moment” was a decision to work towards making a casing that could be disassembled.

“At the end of that first life, can you replace cells? Can you change them over? Is any of that feasible? What we started realising was we were just scratching the surface.

“Because we’re not welding the cells, when they come out of that casing they have the same properties as when they went in, and they are better set up for reuse scenarios.

“[Battery innovation] is driven by performance – further, longer, cheaper … all the things that are going the help the take-up of batteries. But we’ve also got the time to do something right now, to do them in a smarter way. It’s not just about recycling and reuse, but how can we get them into people’s hands.”

‘Flying cars could be on the market within a decade’

In an electric car, the battery can weigh several hundred kilograms – about a third of the car’s total weight.

Audrey Quicke, a climate and energy researcher at the Australia Institute, says about a quarter of the cost of an electric vehicle comes from the battery under the hood.

“Upfront cost is one of the biggest barriers to EV uptake in Australia,” Quicke says. “Although the fuelling and maintenance costs are cheap compared to petrol and diesel vehicles, it’s the upfront sticker price that stands out in the showroom. Any tech developments that bring down the price of batteries would likely help increase EV sales.”

Quicke says a 2018 Senate inquiry recommended a comprehensive EV manufacturing roadmap, which would also cover battery and component manufacturing, but that many of the recommendations remain unrealised.

“EVs and batteries are not a high priority in the government’s technology roadmap, and there’s no federal electric vehicle strategy to speak of,” she says.

Quick GuideHow to get the latest news from Guardian AustraliaShow

Email: sign up for our daily morning briefing newsletter

App: download the free app and never miss the biggest stories, or get our weekend edition for a curated selection of the week’s best stories

Social: follow us on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or TikTok

Podcast: listen to our daily episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or search “Full Story” in your favourite app

“But the writing is on the wall. It is the state governments and tech entrepreneurs that are driving the EV, charging and battery innovation in Australia. Imagine what could be achieved with a nationally consistent supportive EV policy environment to provide direction for this transition.”

Spooner says the company doesn’t intend to produce battery casings at a commercial scale. Rather the aim is to license the technology and to work with manufacturers in Australia and overseas. But he says the ability to reduce the weight of batteries could unlock a second tranche of innovation.

Flying cars, for instance, no longer sound like a film fantasy and could be on the market within a decade.

“It could really open the door here or overseas for vehicle makers and for [vehicles] that don’t exist yet,” Spooner says.

“Locally there’s not a huge EV industry in Australia, but that’s not to say there won’t be. There’s advanced aerospace … manned and unmanned. Stationary storage is here to stay as well.

“Percentage gains in those sorts of fields are really exciting to be a part of – for a car to be delivered as concept, then to be reined in and delivered to the mass consumer.

“The boundaries for new technology to enter the market would be less.

“But batteries also have a big role to play right now. In a lot of ways it’s a mature technology in its early stages of rollout.”

‘You can’t beat the commute’

At the outset of the pandemic as Spooner began to work on the battery casing technology, he spotted a neighbour, an engineer, working in the garage of a nearby home.

Vaulta sublet the space soon after and has no immediate plans to leave. For one thing, it’s too convenient – right around the corner from Spooner’s home, which allows plenty of time to spend with his young daughter.

“When we talk about the garage, it’s actually an upgrade from where we were,” Spooner says.

“We were working from home. We basically worked through emails, phone calls, text messages.

“Through Covid we’ve managed to find a way to do business with Canada, parts of the US. You just kind of adjust and I actually quite like it. You can’t beat the commute and we’re pretty comfortable there, to be honest.”