Satellite images and the latest scientific studies may accurately inform us how quickly the world’s glaciers are melting. But Garrett Fisher’s mission is different: to reveal the “souls” of vanishing glaciers.

This, the American adventurer believes, is best achieved by flying solo over each glacier in a ramshackle antique plane and dangling his camera out of the window to capture their varied forms, textures and beauty – before they disappear forever.

Fisher, a financial consultant who is planning to devote his life to photographing glaciers, has completed his second book. Three years ago, he documented the glaciers of the Rocky Mountains. Now he’s brought his plane to Switzerland to record the glaciers of the Bernese Alps.

Satellite images “can’t replicate the stunning beauty of glaciers”, he says from his current home in Spain, from where he will be embarking on more glacial explorations this summer in his 1949 Piper PA11 plane, which he inherited from his grandfather, who had renovated it after finding it rotting in a barn in North Carolina.

Many glaciers are too inaccessible to reach on foot, or by drone, and helicopters are prohibitively expensive. According to Fisher, his plane, which has a maximum speed of 70 knots – and chugs along at barely 20 knots (23mph) when Fisher dares fly into a 50 knot headwind – uses about the same amount of fuel as a family car.

“With an aeroplane, I can ‘stand’ in a place where a human can’t stand because glaciers are just so brutally unforgiving to cross with their crevasses,” he says. “You can look down into the soul of the glacier from a close perspective.”

Fisher has spent two summers photographing the glaciers of the Bernese Alps, which include some of the most recognisable Alpine scenery, as depicted in the James Bond film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, for instance. He chooses the summer because the glaciers are visible and distinguishable from the surrounding snow. Weather conditions are also slightly more forgiving.

He has to wait for sunshine, with clouds often clinging to the glaciers, and then brave notoriously violent and unpredictable winds – as well as a lack of oxygen – to climb as high as 14,000ft in the Bernese Alps.

“It takes a long time to wait for the right kind of day. The conventional wisdom is that the wind cannot be higher than 20 knots but I’ve gone up in as much as 50. I’m a little special. At high altitudes, the wind tends not to be turbulent if you’re on the proper side of the mountain. So it’s a lot like surfing this giant wave: if you stay in the right spot, everything’s fine.”

He’s only twice been “utterly terrified”: once in Virginia at 3,000ft when his plane was turned upside down by the wind, and another time more recently near Lucerne, Switzerland, where he was “surprised” by vicious winds blowing out of the mountains.

In deep Alpine valleys, he is usually out of radio contact. If his plane got into trouble, the glaciers look like a decent emergency runway, but appearances are deceptive. “Those cavities are so large that if the engine quits and I go in one, the authorities probably wouldn’t ever find me again,” he says. “The risk is improbable, but it’s absolutely worth the risk.”

Experiencing glaciers from a small plane is “exhilarating, transcendental and spiritually elevating”, says Fisher. The images he collects are certainly spectacular. Konkordiaplatz, the meeting point for four glaciers, looks like a spectacular motorway junction of ice, snaking off through the peaks in multiple directions. One picture looks as if Fisher might be about to land on it but such is its scale he took it from 800ft up.

His pictures are taken by sticking a gloved hand out of the plane window with his wide-angle Canon digital SLR. According to Fisher, flying with one hand while taking photos with the other and looking through the camera viewfinder is not as dangerous as taking photographs while driving a car.

“I’ve actually once tried to photograph something with an SLR while driving. You’re in danger of killing yourself in four seconds – you’re 10 feet away from hitting something. In the plane, I’m going at the speed of a car and am usually 1,000ft away from the nearest obstacle. It’s a choreographed art to use what I’m seeing through the viewfinder.”

Konkordiaplatz looks colossal but Fisher’s flying is revealing the rapid melting of many glaciers. He researches each one on Google Earth but finds even recent satellite pictures can be inaccurate because by the time he reaches the glacier he often finds it has drastically shrunk or even disappeared.

Even Konkordiaplatz is 600ft shallower than its 1860 level. “It’s astonishing how much ice has been lost, almost beyond words,” says Fisher. He found another glacier’s “tongue” – its end point, where it discharges water – “scalloping and literally melting like an ice cube”.

Of course, glaciers are always calving and discharging ice and water but Fisher has found he is gradually seeing what’s seasonal and what is caused by global warming. When he flew over Plaine Morte glacier, he admired this “majestic” waterfall that was thundering from the glacier. Usually, the seasonal snow-melt would stop in summer but in 2019 it carried on. “I looked at it and thought, shit. That’s not cool. That was a melt. What drives me is these things are disappearing before our very eyes,” he says.

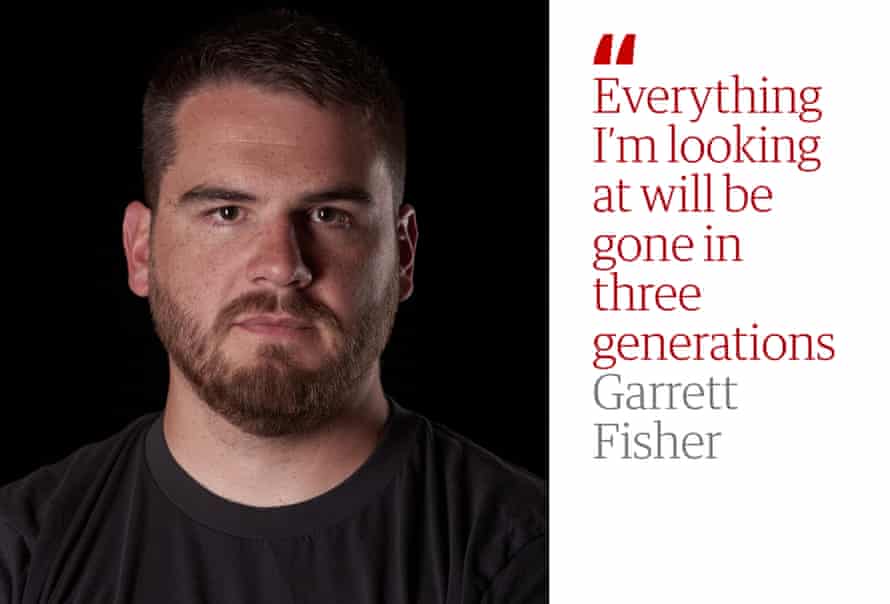

All but two of the Bernese Alps’ glaciers are forecast to be gone by the end of the century. “Everything I’m looking at will be gone in three generations. People will look at these photos like we look at the old British imperial photos of people dressed up watching the locals in Kenya and think, what a weird scene.”

Fisher has now set up a not-for-profit group, the Global Glacier Initiative, with the aim of assembling a personal pictorial record of glaciers around the world to record what is being lost and campaign for more decisive action to combat the climate crisis.

“I’m willing to take the next 20 years and go chase every single glacier I can find on the planet with an airplane and do the same thing,” he says. He aims to put his images into an online map with free licensing for non-commercial uses such as scientific studies and education.

This summer, it is more of the Alps. Fisher then hopes to record glaciers in Scandinavia, Iceland, Canada, Alaska, Mexico, Peru and down the Andes. The Himalayas will require a new plane and the political terrain is almost as hazardous as the geography. “I’m leaving them until last,” laughs Fisher.

“No one wants to live on a glacier so they’re basically publicly owned and they’re global. When I’m dead and gone, someone’s gonna look and say: ‘Holy shit, this is amazing stuff’. I’m doing this for the future.”