The Earth’s climate has always been a work in progress. In the 4.5bn years the planet has been spinning around the sun, ice ages have come and gone, interrupted by epochs of intense heat. The highest mountain range in Texas was once an underwater reef. Camels wandered in evergreen forests in the Arctic. Then a few million years later, 400 feet of ice formed over what is now New York City. But amid this geologic mayhem, humans have gotten lucky. For the past 10,000 years, virtually the entire stretch of human civilization, people have lived in what scientists call “a Goldilocks climate” – not too hot, not too cold, just right.

Now, our luck is running out. The industrialized nations of the world are dumping 34bn tons or so of carbon into the atmosphere every year, which is roughly 10 times faster than Mother Nature ever did on her own, even during past mass extinction events. As a result, global temperatures have risen 1.2C since we began burning coal, and the past seven years have been the warmest seven years on record. The Earth’s temperature is rising faster today than at any time since the end of the last ice age, 11,300 years ago. We are pushing ourselves out of a Goldilocks climate and into something entirely different.

How hot will the summers get in India and Pakistan, and how will tens of thousands of deaths from extreme heat impact the stability of the region? How close is the West Antarctic ice sheet to collapse, and what does the risk of five or six feet of sea-level rise mean for people living on the Gulf coast?

We are in uncharted terrain. “We’re now in a world where the past is no longer a good guide to the future,” said Jesse Jenkins, an assistant professor of engineering at Princeton University. “We have to get much better at preparing for the unexpected.”

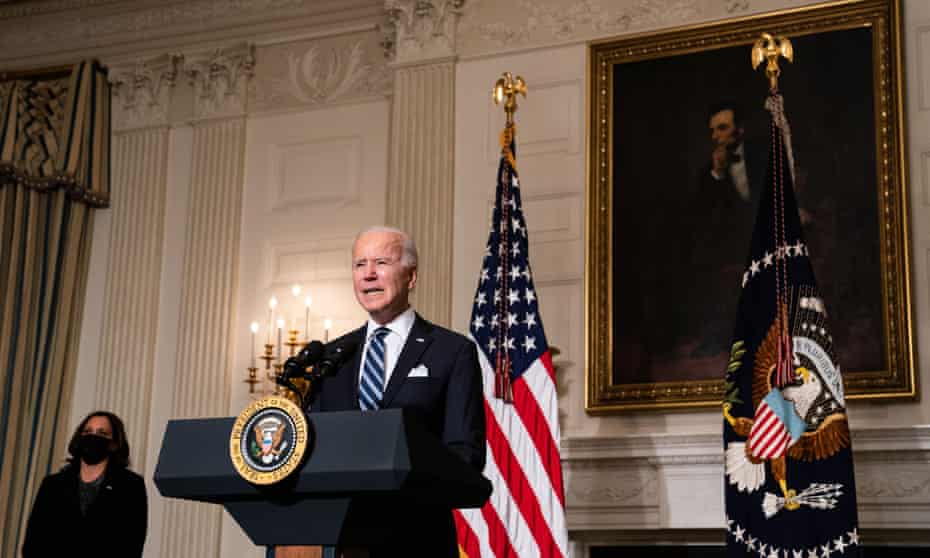

By all indications, President Biden and his team understand all this. In the 2020 election, nearly 70% of Biden’s voters said climate change was a top issue for them. Biden has staffed his administration with the climate A-team, from Gina McCarthy as domestic climate czar to John Kerry as international climate envoy. He has made racial and environmental justice a top priority. And perhaps most important of all, he sees the climate crisis as an opportunity to reinvent the US economy and create millions of new jobs.

“I think in Obama’s mind, it was always about tackling the climate challenge, not making the climate challenge the central element of your economic policy,” says John Podesta, a Democratic power broker and special adviser to President Obama who played a key role in negotiating the Paris agreement. “Biden’s team is different. It is really the core of their economic strategy to make transformation of the energy systems the driver of innovation, growth, and job creation, justice and equity.”

Of course, there have been hopeful moments before: the signing of the Kyoto protocol in 1997, when the nations of the world first came together to limit CO2 emissions; the success of Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth in 2006; the election of Obama in 2008; the Paris agreement in 2015, when China finally engaged in climate talks.

But all of these moments, in the end, led to nothing. If you look at the only metric that really matters – a graph of the percentage of CO2 molecules in the atmosphere – it has been on a long, steady upward climb. More CO2 equals more heat. To put it bluntly, all our scientific knowledge, all the political speeches, all the activism and protest marches have done zero to stop the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels.

But hope rises again. The economic winds are lifting Biden’s sails: the cost of wind and solar power has plummeted by 90% or so over the past decade, and in many parts of the world it’s the cheapest way to generate electricity.

Globally, the signs of change are equally inspiring. Eight of the 10 largest economies have pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. China, by far the world’s largest carbon polluter in terms of raw tonnage (on a per capita basis, the US and several other countries pollute far more), has promised to become carbon neutral by 2060. Some 400 companies, including Microsoft, Unilever, Facebook, Ford, Nestle and Pepsi, have committed to reduce carbon pollution consistent with the United Nations’ 1.5C target, which scientists have determined is the threshold of dangerous climate change.

In her confirmation hearing, the treasury secretary, Janet Yellen, called climate change “an existential threat” and promised to create a team to examine the risks and integrate them into financial policymaking.

Still, these are only baby steps in a very long journey. And the clock is ticking. “When it comes to the climate crisis,” says futurist Alex Steffen, “speed is everything.” If we magically stopped all carbon pollution tomorrow, the Earth’s temperature would level off, but warm seas would continue melting the ice sheets and seas would keep rising for decades, if not centuries (last time carbon levels were as high as they are today, sea levels were 70ft higher). Even after emissions stop, it will take the ocean thousands of years to recover.

Cutting carbon fast would slow these changes and reduce the risk of other climate catastrophes. But despite the world’s newfound ambition, political leaders are not moving anywhere near fast enough. Even the goal of holding future warming to 2C, which is a centerpiece of the Paris agreement and considered the outer limits of a Goldilocks climate for much of the planet, is nearly out of reach. As a recent paper in Nature pointed out: “On current trends, the probability of staying below 2C of warming is only five percent.”

The great danger is not climate denial. The great danger is climate delay.

What’s needed is action now. As climate envoy John Kerry put it at the World Sustainable Development Summit in February: “We have to now phase out coal five times faster than we have been. We have to increase tree cover five times faster than we have been. We have to ramp up renewable energy six times faster than we are. We have to transition to [electric vehicles] 22 times faster.”

Demanding action now will also require shutting down the international financing schemes that support fossil fuels. China, Japan, and South Korea all claim to be doing their part in making carbon reductions at home, while at the same time they are financing 70,000 megawatts of coal power in places like Bangladesh, Vietnam and Indonesia.

The goal of net-zero emissions is also problematic. “Net zero” is not the same thing as zero. It means that carbon pollution is either eliminated or offset by other processes that remove carbon from the atmosphere, such as forests or machines that capture CO2. Some of these offsets and technologies are more legit than others, opening the door to scams that claim to eliminate more carbon than they do.

In a way, the economic chaos caused by the pandemic has created a historic opportunity for the Biden administration. As one White House adviser tells me, “If you are going to pump billions of dollars into the economy, why not use those dollars to help us transition away from fossil fuels?” This is one of the central ideas behind Biden’s $2tn infrastructure bill, which is now being negotiated in Congress.

Already the pushback is fierce, especially in states that have benefited from the fracking boom. Shortly after Biden issued his first round of executive orders aimed at the climate crisis, the Texas governor, Greg Abbott, held a press conference in the middle of the gas fields “to make clear that Texas is going to protect the oil-and-gas industry from any type of hostile attack launched from Washington DC”.

Republicans, along with stalwart fossil-fuel allies like the Heritage Foundation, recently convened a private retreat in Utah to plot ways to “reclaim the narrative” on climate, while Republican senators like Tennessee’s Marsha Blackburn continue to recycle tired old rants about how the Paris agreement is destroying American jobs.

Every day it becomes clearer that the fight for a stable climate is increasingly inseparable from a fight for justice and equity. Catherine Coleman Flowers, who was on a taskforce that helped shape Biden’s climate policy during his campaign, grew up and works in Lowndes county, Alabama. “I see a lot of poverty here,” Flowers says. “And I see a lot of people who suffer from the impacts of climate change – whether it is heat, or disease, or poor sanitation and polluted drinking water. You can’t separate one from the other. They put sewage lagoons next to the houses of poor people, not rich people. They put oil pipelines through poor neighborhoods, not rich ones.”

For more than 30 years now, scientists and politicians have been aware that our hellbent consumption of fossil fuels could push us out of the Goldilocks zone and force humans to live in a world we have never inhabited before. As Biden’s push for climate action gets real, we will learn a lot about how serious human beings are about living on this planet, and how far the powerful and privileged are willing to go to reduce the suffering of the poor and vulnerable.

If political leaders don’t take the climate crisis seriously now, with all they know, with all they have been through already, will they ever? “Climate advocates keep saying, ‘This is it, this is it, this is it,’ ” warns Podesta. “But this really is it. If we don’t amp up and accelerate the energy transformation in this decade, we’re goners – really goners.”

This story originally appeared in Rolling Stone and is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story