Last November the Marine Biological Association (MBA) – one of the world’s longest-established bodies dedicated to research into our oceans and its ecosystems – led the first online Young Marine Biologist summit. Attracting more than 350 young people from 35 countries, the event, which celebrated the start of the United Nations’ Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-30), was also used to launch the Ocean Decade writing challenge.

In an initiative led by MBA science communicators working with the marine biologist, broadcaster and Guardian Seascape contributor Dr Helen Scales, the challenge asked contestants to consider “10 years in the ocean”. What could change in science or the way we use and protect the ocean? What might be discovered?

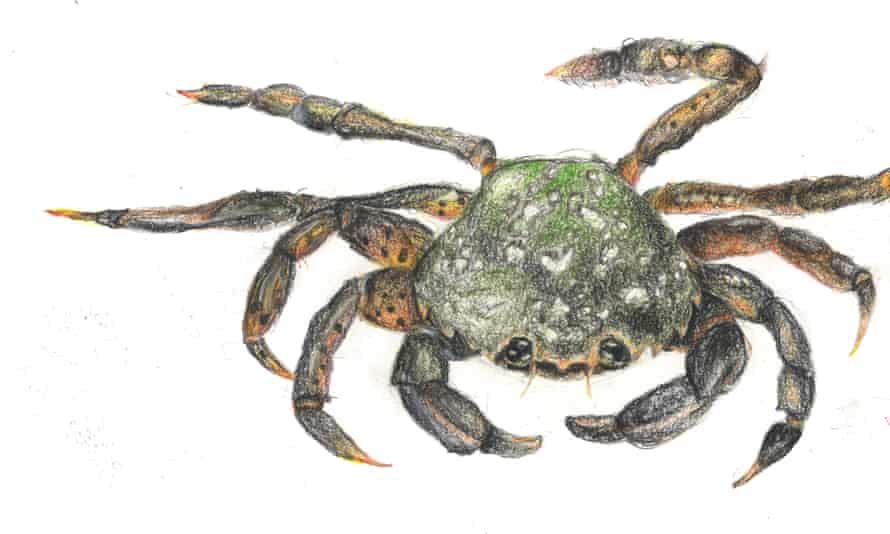

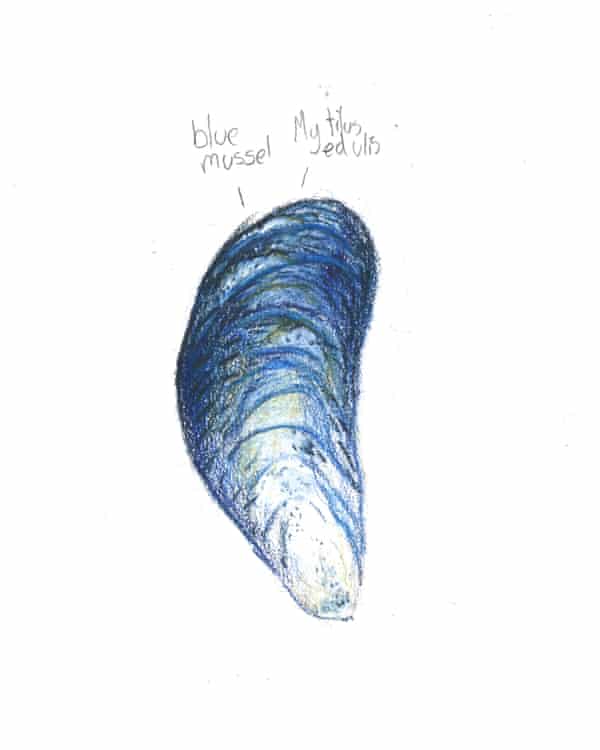

Entries were received from young authors around the world who explored their own personal relationships with the sea, and were encouraged to let their imaginations and creativity run wild. Two of the entries are published here, with illustrations by the winner of the younger age category, Ellie Sillar. We hope you enjoy them.

Winner of the age 14 and under category: Ellie Sillar

My ocean decade

“Quickly! Come quickly! The otters are back!” My voice rings out around the house, inciting a scramble for shoes and a race to the door. My family and I pile outside, then make lots of noise shushing each other, before settling into an awed silence as we witness an otter devouring its latest victim: a sizeable shanny – a type of blenny.

I have often seen otters while on annual holidays in Kildonan, Arran, but each new sighting is almost as exciting as the first. During their time on shore, otters chase around rock pools, tease unsuspecting fish from their hiding places and find some comfy basalt rock to sit on while enjoying their meal. But they never stay long, soon swimming out to sea in search of more food. Otters eat 15 to 25% of their own body weight every day, snacking on crabs, clams, fish and urchins.

When walking along the beach, I often find broken shards of urchin shells along the strandline. But by far the best chance to get a good look at complete urchins is by snorkelling. Edible sea urchins live on the seabed at up to 40 metres deep, but at low tide I can usually find some nestled in cracks and crevices in water barely a metre deep. I take a deep breath and dive down for a closer look, my hands search the rocky surroundings for wedges to hold myself down to the shallow seabed. Now, secured in position, I can observe the urchin. Urchins are grazers feeding on many things such as barnacles, plankton, mussels and algae.

One such algae is oarweed. A brown seaweed, commonly referred to as kelp, oarweed has a broad body that separates into finger-like digits (hence the Latin name Laminaria digitata). Once I have swum out to deeper waters, the tangling masses of loose seaweed give way to swathes of kelp forest, with just enough room between the seaweed and the surface for me to glide over. Oarweed grows very fast, increasing by up to 5.5% a day.

While kelp forests cover a large proportion of Arran’s seabed, there is another habitat that is equally rich in wildlife: maerl beds. Maerl is a collective term for certain red coralline algae that grow on the seabed. There are three main species found in the UK, two of which I have seen in Arran: Phymatolithon calcareum and Lithothamnion glaciale. I plunge down into the water, but maerl tends to grow at least 3 metres deep so by the time I have a clear view, I don’t have long to explore my surroundings before having to return to the surface.

The main way in which maerl reproduces is through fragmentation. Pieces of maerl attached to sugar kelp can be transported considerable distances during storms, allowing maerl to colonise new areas. Maerl beds support an incredible biodiversity (providing a nursery for juveniles of many species) though individuals only grow 2cm a decade. The formation of a substantial maerl bed can take an extremely long time. However, it can be decimated in days. Dredging exploits the rich resources of prawns and scallops, ripping up countless tons of maerl and kelp leaving behind a barren waste resembling a freshly ploughed field.

In 2008, Arran’s Lamlash Bay “no-take-zone” (NTZ) became the first community-led marine reserve in Scotland, with a 50% improvement in biodiversity noted in the first decade. This 2.67 sq km (250 acre) marine reserve protects one of the largest maerl beds in Scotland, which has probably been growing since the last ice age. Building on the achievement of the NTZ, protection of a further 280 sq km around Arran’s coast (including Kildonan) was proposed in 2012, with legal enforcement in 2016 outlawing dredging.

This is what we can achieve in a short space of time. So, yes, these habitats grow slowly. Yes, they can be destroyed in mere hours. But in less than a decade we can protect them for centuries to come.

Winner of the 15 to 18 age category: Ana-Maria Munteana

A decade in the ocean

“Ocean, ocean … what’s so awesome about it? It’s just water, Ana. You can’t be obsessed with water.”

I assume you get to hear that a lot too. Do you know how to respond? Do you actually have a definite answer? Because I don’t. I just go with what feels right for me when I think about the ocean: I do love it. However bizarre it might be for some, I love it because it’s calm, beautiful, infinite; but also angry, harsh, magnificent in its wrath. This duality is what intrigues me most. All this “just water” on our planet calls to me, screaming from afar: “Freedom.”

Let’s talk about my feelings for this vast area of joy and enthusiasm and adrenaline and … There aren’t enough words in this world to explain the feeling you get when you let yourself “go with the flow”. Literally. As for my journey, it begins after getting accepted into my dream high school in Romania. Yes, Romania. Romania that doesn’t care about its sea or rivers and has beaches covered in plastic. Romania, which actually does not have an ocean.

The moment when I realised what I wanted to do with the rest of my life was in Year 10. Nothing spectacular happened, like in the movies. I didn’t get sparkling eyes after being inspired by an ardent speech of a famous marine biologist. I was simply scrolling on Instagram when, unexpectedly, a girl from Australia appeared on my feed.

The post had so much blue in it, and because my favourite colour is blue, I felt the urge to look for more of her posts. Are you confused right now? Yes, I discovered my passion through the internet. Another medium that has no borders and seems to symbolise pure freedom. This one post made me wonder what else there is to biology, a subject that I have to admit I was never too interested in. This obvious choice for me didn’t click with others, just as well though.

My mum didn’t agree, my friends were speechless. Nobody, other than my father, believed in me. My mother said I cannot make a career out of this and is still worried that finding a job will be impossible. She hates that I’m not going to be a doctor or a lawyer or an engineer. I speak of all the misdeeds we purposefully carry with us, the continuous struggles of teenagers, but also about people who have nothing to offer us but a push – a push to get out. So I will.

For many the ocean is a faraway place, easily forgotten, and disconnected from everyday life. It’s difficult for people to envision an ocean like this: full and alive, like the beat of a giant collective heart. All is connected and all affects us. We have to wake up and accept the fact that we are not in a good situation. This is why we aspire to build a comprehensive understanding of the ocean and its governance systems. We do need marine biologists. Yes, mum, we do. Unless you want to wake up without water in the next 10 years. Read this carefully: choose a job you love and you will never have to work a day in your life. You hadn’t done that. So I will.

I would rather die of passion than of boredom. Each and every one of you that is reading this right now: dare to take initiative! Dare to make a change! And please, dare to believe in yourself. Because I do. I will follow my path to achieve the dream of restoring corals and fighting for the fate of our society. I hope you will follow your path too. Be fearless in the pursuit of what sets your soul on fire.