Ma Jun experienced a strange role reversal during Donald Trump’s presidency. Over more than two decades as one of China’s top environmental campaigners, American encouragement for Beijing to cut carbon emissions and temper the damage of rapid industrialisation had been part of the background music. Ma never imagined he would see the US renege on environmental commitments while China began to face up to the challenge.

“It’s been frustrating,” says Ma of the past four years as we speak on the phone, the bustle of Beijing audible in the background. “When it comes to environmental collaboration between the governments, it has been hard to do anything.”

Before the US election, the Chinese foreign ministry issued a 12-point excoriation of Washington’s record on the environment, criticising the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement and failure to protect wildlife – even condemning methane gas leaks from fracking. While the criticisms were likely made in response to a similar State Department factsheet in September, the old dynamic between the two powers on the environment appears to be over.

“China has started changing its course. We have seen a lot more ‘walk the walk’ action. China has adopted some tough measures to try to deal with the pollution and environmental damage problem. And we have seen some progress made because of that,” Ma says.

When the 52-year-old former investigative journalist wrote the now seminal China’s Water Crisis – published in China in 1999 and the west in 2004 – air pollution, contaminated water and deforestation were largely accepted as the price of China’s rapid economic development. Ma’s writing on the pollution crisis helped provoke an environmental awakening.

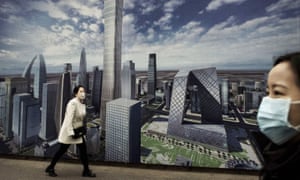

More than two decades later, China is preparing to host major talks on the environment for the first time at Cop 15 in Kunming in 2021, where the international community will sign up to a Paris-style agreement for nature. President Xi Jinping has pledged to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060 and ensure China’s greenhouse gas emissions peak during this decade. The next five-year plan, currently being developed, could be the greenest yet.

“I think most importantly for China to change its course was the voice made by the Chinese people, by the citizens,” says Ma. “The issue around smog has made a big difference. So many started making their voices heard. Eventually, the government started monitoring and disclosing truthful information.” While more than a million people still die early every year due to air pollution in China, the number of deaths has started to drop and air quality is improving.

“The more action taken, the more confidence it gives to decision makers that it will not lead to a massive disruption of society,” adds Ma.

Undoubtedly, many challenges remain. Environmental concerns surround the multibillion-dollar belt and road initiative – likely to guarantee China’s role at the heart of international trade for the next century. Parts of the illegal wildlife trade centre on China, driving species extinction across the planet. The current pandemic has only heightened the scrutiny.

“Covid-19 has taught people a harsh lesson that we must think more about the relationship between man and nature,” says Ma. “But Sars has taught us that lesson before. People sometimes have a short memory. People understand that we should not consume those wild animals but unfortunately when the pandemic is over, it’s coming back in some way.”

China’s government has issued a temporary ban on wildlife markets, just as it did after the 2002-3 Sars outbreak. Campaigners in China have called for the government to make the ban permanent. Ma says he is building an AI app with his partners that will help identify animals that are part of the illegal wildlife trade and are being sold at markets and report the incidences to agencies.

“Some people have been found bringing products like ivory and rhino horn into China. I think, increasingly, people are starting to recognise that it’s immoral – not just illegal, immoral. Our younger generation of Chinese, they tend to have a much higher understanding of this.”

If the app is successful, it would be the latest in a series of data-led tools helping China make changes on the environment. The Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, an organisation Ma founded in 2006 that has since become China’s top NGO, provides a live pollution map of the country with data on air and water quality accessible to everyone. People can monitor the outputs of nearby factories and report evidence of environmental violations through the Blue Map app.

Ma says the data has encouraged about 16,000 factories to improve environmental standards, many of which form part of the supply chain for major western companies such as Apple, Levi’s and Primark. It has also encouraged the Chinese government to improve its environmental record.

Ma’s mission to restore the blue skies and clean water of his youth to Beijing received a further boost with the election of Joe Biden. Hope has returned, he says, the change in tone noticeable from the first time we spoke in October, on the eve of his participation in a Global Landscapes Forum event on the importance of biodiversity in preventing future crises of pandemics and climate change.

“There’s so much that could be done by the two countries [China and America]: the two largest economies, the two largest emitters. There’s so much that they should do together,” he enthuses about Biden’s commitment to rejoin the Paris agreement. If the president-elect’s $1.7tn green investment spending plans are carried out in full, his presidency could reduce global heating by 0.1C, according to recent analysis by Climate Action Tracker. That said, Biden is likely to face intense opposition from Republicans at state and federal levels.

“I hope there’s healthy competition between the two countries,” Ma continues. “Hopefully they can see the opportunities, not just costs and risks, but also huge potential for a green recovery and green growth.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features