In August, Adrienne White – an ice analyst at the Canadian Ice Service who monitors the Canadian Arctic for changes in sea ice – was reviewing satellite imagery when she spotted something remarkable. The enormous Milne ice shelf, which was the last intact ice shelf in Canada and which White had studied closely before as a PhD student, was dissolving.

A huge chunk larger than Manhattan, roughly 43% of the shelf, broke off in one piece. And as it collapsed into the ocean, it took with it much of the equipment her former colleagues had left there.

“It is lucky that we were not on the ice shelf when this happened,” one colleague, Derek Mueller, wrote in a blogpost following the discovery. “Our camp area and instruments were all destroyed in this event.”

Mueller had been studying a channel that ran below the surface of the Milne ice shelf, like a river. In 2017, a team of researchers discovered scallops, sponges, worms and other organisms living some 20 meters deep, inside the ice shelf. Animals have been found living beneath ice shelves before, but never – to Mueller and his colleagues’ knowledge – inside of one.

Mueller is one of Canada’s leading ice shelf experts, along with Luke Copland, who supervised White’s PhD. Together and separately, the three have been studying the Arctic for years. They had observed rifts appearing over the Milne ice shelf throughout their careers. Still, the breakup – known as a calving event – is significant. Copland believe ice shelves are “a canary in the coalmine” in the climate crisis, given that they are especially susceptible to atmospheric changes.

We spoke them about what that day was like, and where they go from here.

How did you first learn of the calving event?

Adrienne White: At the Canadian Ice Service, we use satellite imagery to chart sea ice in Canadian waters. We also use this imagery to monitor glaciers and ice shelves for calving events that can produce large ice islands. The day I discovered the Milne ice shelf calving event was a typical day; I came into work and was looking along the coastline of Ellesmere Island [to which the ice shelf was connected] for any changes; over the previous week, I’d noticed there was a lot of open water in the area, which can lead to destabilization.

Looking first at the optical imagery, the same type of imagery you would see on Google Earth, I could see that there was a darker area on the Milne, but there were a lot of clouds on the image that I couldn’t see through. Then I used radar satellite imagery, which can penetrate clouds, and with that we were able to clearly see the ice islands were separating from the ice shelf, and that the calving event was taking place.

What was your first reaction?

Derek Mueller: Shock and sadness, in some ways. It’s like hearing bad news. It’s not an easy thing to get used to.

White: I was really surprised. We think of these as semi-permanent features. But the breakup of these ice shelves is really quite inevitable at this point; along the coast of northern Ellesmere Island, we’re seeing open water and warmer temperatures almost consistently every summer.

Luke Copland: I got a text from Adrienne – I remember it clearly – and it just said: “The Milne ice shelf is gone.” I saw it and thought, ‘Crap, is that real?’ We’d both spent a lot of time working and living on the ice shelf, flying around it, studying it, so I texted her back and she described the process and the timing.

Did you see it coming?

Mueller: All of the other ice shelves had broken up in past years, so it wasn’t a question of if for this particular ice shelf. It was a question of when.

Copland: If you look at the changes [over time], we’ve lost more than 90% of ice shelves in the last hundred years. We’d seen increased melting on the surface and the bottom [of the Milne], as well as long-term thinning. So we knew things were changing. Still, this ice shelf is huge, it’s bigger than large cities are, and it’s very strange to look at a satellite image one day and then look at [the same area] the next day, and the thing doesn’t exist any more.

White: I always thought that the Milne was one of the more stable of the ice shelves; we had seen major breakups from the neighboring Serson and Peterson ice shelves, but the Milne seemed less susceptible to breakup. Part of my PhD was looking at what made it so stable, [including] the fact that it was so much thicker and attached to the walls of this fjord.

That being said, it did have large fractures going across it that had been widening over the past few years. And we had seen the southern edge, the part of the ice shelf at the back of the fjord, starting to melt away more and more each year. Still, it was a shock to see the thickest, strongest part of the ice shelf break apart in this one big piece.

Did you ever think you’d lose your equipment to an event like this?

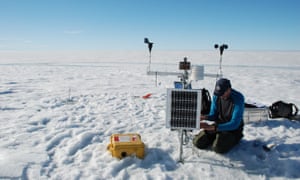

Mueller: It’s one of those things: We need the data year-round and we can’t stay there year-round, so it’s always a risk. You could put a weather station on a tripod on a glacier and it could fall over. There’s lots of instruments floating around the Arctic that people [had] put out. We got two full years of data from ours, so we count ourselves lucky in that sense.

Does this change your plans to study the area?

White: Absolutely not. It only shows us how important it is to continue monitoring this coastline and acquiring imagery in this specific area at even higher resolution

Copland: We’re shifting more towards [studying] satellite images. A colleague of mine actually died [in the field]; he was one of the world leaders studying glaciers in the Arctic, and he fell through a crevasse on the Greenland ice sheet. And it seems that that crevasse is filled with water, which is ultimately the result of climate change.

There’s also been a shift over the last few years to studying [the Arctic] by helicopter. There’s so many measures that we can’t make unless we’re in the field; for example, we can’t really measure how thick the ice is from space. Moving forward, we’re still planning fieldwork, but being very careful and planning around safety.

Mueller: The ice shelf is still half there. Our key study site on the ice shelf was lost, but we can find another study area potentially.

Is it too late to save Canada’s remaining ice shelves from further breakup?

Copland: For ice shelves, we can lose them very quickly; when they break up, that piece of the ice shelf is gone, it floats away. That takes a day. But to form an ice shelf, it takes hundreds to thousands of years, because you need a gradual buildup of snow and ice. You need a cold climate for centuries to form an ice shelf, but to lose one, you lose them immediately.

White: This is really an area that has changed from [once] being completely ice-covered. You [used to] have old sea ice attached to the coast and ice shelves filling fjords and bays. Now, every year, we’ve seen open water along the entire coast of Ellesmere Island. The entire icescape has changed.

Mueller: I always have to say yes, it’s too late. Ice shelves were already vulnerable to change. But the action we take now will prevent this – or mitigate it, anyway – in the future, in other places. It’s critically important that we heed these warnings. If we can make a change and hit these Paris climate accord targets, there is opportunity.