Franco Comes last caught sharks more than six months ago, while longline fishing for swordfish in the Adriatic Sea off the coast of Monopoli, Italy. He hauled in an accidental handful of blue sharks. They were tiny.

“They are fewer and fewer, and they are also becoming smaller,” Comes says. “Twenty years ago, there used to be so many sharks – so many! They seem to have decreased by 80%. It’s not just me: every fisherman around here has noticed.”

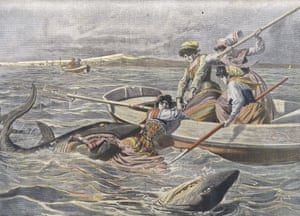

Sharks have populated the Mediterranean for millions of years; paintings of sharks on vases precede the Roman empire. A century ago, there were so many white sharks in the Adriatic that local authorities reportedly paid fishermen to go on a killing spree.

But the Mediterranean has now become the world’s most dangerous sea for sharks, biologists say. As fishing crews pushed to catch ever-higher numbers of tuna, swordfish and other species, more sharks ended up in their nets – and now shark meat is increasingly being sold as something else to shoppers and diners.

Today, more than half of the 73 species of sharks and rays found in the Mediterranean are at risk of extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Shortfin mako, white and basking sharks, and many others, have been decimated. Some shark populations have dropped by up to 90%. Even some species that are doing relatively well elsewhere – such as the blue shark, a deep blue and white species growing to about three metres – are critically endangered in the Mediterranean.

Pollution and climate change could be having some impact, says Simone Niedermuller of the WWF Mediterranean Marine Initiative, but much of the scientific evidence points to another culprit. “It is clearly fisheries that are the main threat.”

Spain’s blue shark catches on its Mediterranean coast doubled between 2012 and 2016, according to the WWF. While few Mediterranean fisheries target sharks directly – their meat is inexpensive and provides thin margins – sharks are often bycatch in the search for more lucrative prey, such as tuna and swordfish.

In the past, fishing crews would put most sharks back into the sea. But Niedermuller says fishermen could be looking to sharks to supplement their incomes, which are often falling as other stocks dwindle. A recent study by the EU’s Joint Research Centre said almost all of the Mediterranean’s fish stocks are overexploited, and that in the past 50 years the region had lost a third of its fish.

“What they would have put back into the sea, many fishermen are now landing, marketing and selling, often illegally and without proper labels,” says Niedermuller. “Sharks [have] filled a hole that other seafood commodities left.”

A cheap seafood that can be cooked in ways that make it unrecognisable, shark meat often finds its way to restaurants, stalls and tables in Europe, particularly in Italy and Spain. Many consumers appear to be unaware they are eating shark.

“Very few people eat shark meat knowingly,” says Simona Clo, the scientific director for MedSharks, an Italian wildlife NGO, and a member of the IUCN Mediterranean regional group.

“Sometimes it happens because a species’ common name might be misleading,” she says. For example, the Italian for blue shark (verdesca) has little to do with the word shark (squalo).

Other times, she says, shark meat is added to dishes where it would be difficult to recognise, such as mixed fried fish and fish soup.

In the worst cases, shark meat is fraudulently marketed as more expensive seafood species. The trade is lucrative. A kilo of blue shark can sell for about one euro. Swordfish is worth up to 12 times as much. “The margins are huge,” says Pierluigi Carbonara, a marine biologist working with the Monopoli fishermen and the WWF in Puglia. “I’m not an economist, but I think even a child would understand why it happens.”

Q&A What is the truth about sharks series?

Show

Hide

Mysterious and often misunderstood, the shark family is magically diverse – from glowing sharks to walking sharks to the whale shark, the ocean’s largest fish. But these magnificent animals very rarely threaten humans: so why did dolphins get Flipper while sharks got Jaws?

Sharks are increasingly considered, like whales, to play a crucial role in ocean ecosystems, keeping entire food chains in balance – and have done so for millions of years. But these apex predators are now in grave danger. The threats they face include finning ( in which their fins are sliced off before they are thrown back into the water), warming seas, and being killed as bycatch in huge fishing operations.

To celebrate our emerging understanding of sharks’ true nature and investigate the many underreported ways in which humans rely on them, the Guardian is devoting a week to rethinking humanity’s relationship with the shark – because if they are to survive, these predators cannot be prey for much longer.

Photograph: Good Wives and Warriors

According to the Italian Coast Guard, the fraudulent sale of shortfin mako or blue shark as swordfish is one of Italy’s three main seafood scams. A study by the University of Catania last year found that 15% of the samples of swordfish it analysed contained traces of other seafood. Another piece of research by the same university found that four out of five samples of dogfish, or mud shark, from a fish market in Milan belonged to other shark species.

Data around seafood fraud is scarce and evidence often anecdotal, but many believe it to be widespread. “When researchers and NGOs run tests to understand the magnitude of the problem – everywhere we look for it, we seem to find it,” says Nicolas Fournier, campaign director at Oceana Europe, a non-profit ocean conservation organisation.

These frauds can expose consumers to health risks, as shark can contain higher levels of mercury and other metals than other species.

They are also illegal, of course, but Fournier says uneven enforcement and different reporting mechanisms across countries have allowed the practice to continue.

Moreover, most global fisheries of sharks and rays are unregulated. In 2012, the EU moved to ban loopholes that allowed finning, the practice of slicing off the fins of a shark – which are considered a delicacy in some Asian countries – and throwing the live body back to sea. According to existing rules, crews can only land sharks with their fins attached, but trading the fins remains legal, even if they are from locally endangered species such as shortfin mako and blue shark.

Sharks are also more vulnerable to overfishing because most have slow life cycles. Some species achieve sexual maturity at 15, have only a handful of offspring, and live up to 50 or 60 years.

There are concerns that unsustainable fishing could lead to the proliferation of some species and the extinction of others. Sharks are apex predators, and their disappearance could send unpredictable ripple effects throughout the environment, biologists say.

The Mediterranean is already changing rapidly, Niedermuller says. Better controls to ensure that fisheries are legal, traceable and sustainable are vital.

“We need sharks as stabilisers, as a kind of security for the future,” she says.

Share your thoughts and experiences using the hashtag #sharklife on Twitter and Instagram, and follow our shark series at Guardian Seascape: the state of our oceans