Scott Morrison’s net zero modelling reveals a slow, lazy and shockingly irresponsible approach to ‘climate action’

The modelling was delayed until the final Friday of COP26 to avoid embarrassment. But it’s even worse than expected

In April this year, Australia’s prime minister, Scott Morrison, said that “we will not achieve net zero in the cafes, dinner parties and wine bars of our inner cities”. This explains why he turned to the salt-of-the-Earth hard-workin’ rural folk at McKinsey – one of the biggest billion-dollar multinational consulting agencies on the planet – to produce the Australian government’s long-awaited modelling explaining the pathway to “net zero by 2050”.

In some parallel universe, the task may have gone to Australia’s chief science agency, the CSIRO (a former employer of mine). But it was revealed at Senate estimates a few weeks back that despite the CSIRO applying for the tender, the government rejected them and paid McKinsey $6m to model the changes Australian society must go through to decarbonise within 30 years. This choice makes sense in the context of recent leaks to the New York Times that revealed McKinsey has advised 43 of the 100 biggest corporate polluters, including “BP, Exxon Mobil, Gazprom and Saudi Aramco”. 1,100 of its employees signed an open letter pleading the consultancy reveal the carbon impacts of its clients.

We’ll never know exactly what the Australian government asked of the agency, but we finally know what got spat out the other end: an extremely weird document blatantly designed to protect the interests of Australia’s fossil fuel industries while creating the illusion of ambitious climate action. It was delayed until the final Friday of Cop26 to avoid embarrassment during the global deliberations, so we knew it’d be bad. But it’s worse than expected.

Earlier this year, I published a collection of predictions on what tricks and loopholes the Morrison government would use to announce a net zero target while changing nothing of Australia’s climate policies and emissions.

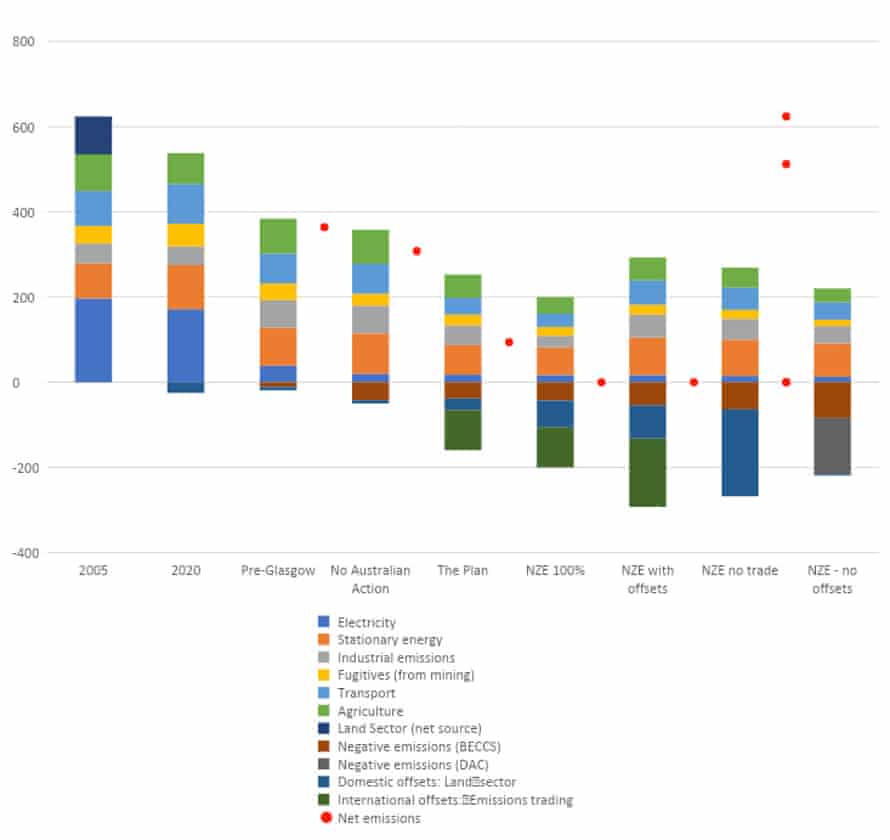

Some, I was right about. The government is indeed “backloading” its climate action. This means putting off action until after 2030 and 2040, and changing nothing in the short term.

The government is also, as expected, relying heavily on “offsets”. This involves justifying greenhouse gas emissions on the grounds some other purchased service “cancels” them out. This can be the active removal of carbon from the atmosphere (the least bad option), or, ludicrously, the avoidance of emissions (such as a farmer choosing not to clear land). In McKinsey’s modelling, these offsets are cheap as chips because they’re mostly low-quality offsets like avoided emissions or carbon stored temporarily in trees and soil. It also entails the creation and participation in international carbon markets. This is the deeply problematic “net” in “net zero”, and it’s a growing problem both in Australia and around the world.

If you want an idea of just how you should feel about offsets, imagine for a second if Morrison proposed dealing with the threat of Covid-19 by paying people in New Zealand to stay at home when they want to go out, and justifying an absence of restrictions in Australia on those grounds. It’s raw madness in any other context, but somehow, in climate, we’ve been bullied into treating it as normality.

Here’s what I didn’t predict: of the various pathways modelled in this document, Australia’s government picked the one that doesn’t even reach net zero by 2050. Their preferred scenario, “The Plan”, hits 2050 with a whopping 94 megatonnes of emissions remaining, or 215 if you exclude questionable offsets. They reached the point of 85% reduction in emissions, and very simply gave up. This ignored 15% is breezily labelled “further technology breakthroughs” in the document. It’s both amusingly honest and stunningly irresponsible.

As RenewEconomy’s Michael Mazengarb pointed out on Twitter, they also modelled a scenario in which emissions reductions go all the way to zero, albeit also reliant on offsets. That has a near-zero impact on economic growth, but it’s explicitly dismissed because this scenario also results in worse outcomes for the coal and gas mining industries.

Coal and gas sent overseas is responsible for roughly three times Australia’s annual domestic emissions. If the 72 coal projects and 44 oil and gas projects in Australia are realised, this will become six times Australia’s domestic emissions. They won’t all be realised, but you get an idea of their wide-eyed fantasies of growth. It’s this massive engine of planetary warming that the net zero plan ring-fences. Snarling at threats to fossil fuel companies feels like the only imperative this document takes seriously.

There is a reserved concession to the possibility that the coal export industry may shrink, with one graphic showing future coal exports dropping by 50%, by 2050. But in the same chart, gas exports increase by 13%. Both are laughable, considering the International Energy Agency’s “net zero by 2050” global scenario sees the total global consumption of both coal and gas drop to near-zero by 2050.

Part of why this discrepancy exists is that the IEA’s net zero scenario is limiting warming to 1.5C, but the government is targeting 2C, which allows for worse emissions into the future at the cost of more severe and catastrophic impacts of warming, particularly in the Global South. In fact 1.5C is not mentioned a single time in the hundreds of pages of the report. Like the 85%, it just breezily gives up part-way there.

Fundamentally, what McKinsey has laid out for us is that if you take the laziest, slowest and most bad-faith approach to climate action, it’s very cheap and not immediately disruptive. Take credit for technological advancements that occur in other countries, continue extracting and emitting in the interim, and slap it all with a counterfeit climate action label to avoid scrutiny. Being a tech free rider while worsening the problem you claim to be solving is a wonderfully tempting climate philosophy.

Of course, McKinsey’s modelling buries an important caveat in the guts of the PDF: the physical consequences of climate change are not included in their modelling. That means they count the benefits of falling back to slower action and worse emissions, and ignore the consequences.

In reality, we cannot ignore the consequences. Climate change is a physical problem in which the accumulation of greenhouse gases heats our habitat and hurts us, very badly. A tower of greasy tricks deployed to protect the fossil fuel industry changes nothing about the laws of atmospheric physics, and the pain we experience when governments don’t act fast enough.

Australia is not alone in exploiting the void between shiny promises and the hard realities of immediate, substantial change. The Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit’s “Net Zero Tracker” outlines in great detail the unnerving gaps in the implementation of net zero targets. Several analyses of promises at Cop26 highlight the same.

Truly, though, there is no country in the world that does climate delay quite like Australia. The hammy nationalism, the role of fantasy and trickery in its climate and energy rhetoric, and the total absence of shame in defending its role as a key cause of significant physical damage to Earth. It’s only going to escalate as the next federal election inches closer. Better strap in: it’s going to get even weirder.