‘I get scared’: the young activists sounding the alarm from climate tipping points

From Philippines to Greenland, protecting dying coral reefs to melting ice sheets, young people are fighting for their futures

For millions of young people around the world, climate breakdown is something they have known their entire lives. Many live in regions that are particularly at risk of being affected by tipping points – parts of the Earth’s system where small changes, such as increased temperatures, could lead to accelerated and irreversible impacts.

A landmark IPCC report earlier this year warned that tipping points such as melting ice sheets or Amazon forest loss could soon be triggered, with the potential to bring catastrophic change to vulnerable areas.

But rather than be paralysed by fear, these young activists are taking action. From protecting coral reefs to organising protests, they are doing what they can to try to stop the tipping points from being passed.

“They’re doing it right,” says Prof Tim Lenton, a leading expert on climate tipping points from the University of Exeter. “[They are] alerting the rest of the world from its slumber to tackle climate change and to transform society.”

Jon Bonifacio, 23, Metro Manila, Philippines

Jon Bonifacio grew up hearing about the Philippines’ coral reefs. He pictured brightly coloured underwater worlds, where marine life could flourish.

But when he finally got to visit a reef a few years ago, what he saw told a different story. “The coral reefs seemed completely lifeless,” he says.

Rising sea temperatures are pushing the world’s tropical coral reefs past a tipping point where they now suffer bleaching events almost every year. While scientists say there is still a chance to prevent several tipping points, coral reefs face a bleak future: even if temperature rise is limited to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, it has been projected that 70%-95% of coral reefs will be gone by the end of the century.

When Bonifacio learned about this, he dropped out of medical school to pursue climate and environmental advocacy full-time. He joined local environmental groups, advocating for companies and governments to do better, tried to prevent reclamation projects that threaten to bury marine reserves, and even swam to reefs to remove crown-of-thorns starfish that eat corals – a small cause of reef die-off.

“I like what they’re doing,” says Lenton. “Even if it’s hard to change the global climate, activists can reduce other pressures on the reef.”

While there are days when Bonifacio is “paralysed by the anxiety of what the next few years and decades could bring,” he has not given up hope. Supporting local science and research institutions, he says, is a concrete way to help. “We still do have a chance at life worth fighting for.”

Adri Mafoletti, 18, Porto Alegre, Brazil

Over the course of Adri Mafoletti’s life, the Amazon rainforest she grew up in has lost more than one-third of its capacity to absorb carbon.

Logging and the climate crisis has resulted in the loss of trees. Now, scientists estimate that 40% of the existing Amazon rainforest could become a savannah, pushing it past its tipping point and reducing the planet’s ability to absorb carbon.

For indigenous communities living in the Amazon, crossing this tipping point would also mean an end to their way of life.

“Indigenous peoples cannot live without forests and rivers – it’s all we have, it’s part of us,” says Mafoletti, who is part of the Guarani community. “We are nature, without it we don’t exist.”

Mafoletti is doing all she can to fight climate change. She makes sure indigenous groups on the frontlines have access to basic goods and raises awareness of how the climate crisis exacerbates gender inequality.

Nanna Chemnitz Frederiksen, 18, Nuuk, Greenland

Nanna Chemnitz Frederiksen grew up in Nuuk, Greenland, where every fraction of a degree of heating is made visible by the ever-shrinking Greenland ice sheet.

“People from all around the world, politicians and scientists come to Greenland to see the inland ice,” she says. “We are at the centre of this.”

A significant portion of the ice sheet is thought to be on the verge of a tipping point, where melting could soon become unavoidable even if emissions are cut. The ice sheet is hugely important to stabilising the global climate, as it provides a vast white regionthat reflects sunlight back into space. But as the ice melts, the reflective surface shrinks, leading to more warming and melting and in turn, sea level rise. Scientists say sea level rises of one to two metres is probably already inevitable.

Frederiksen knows that the melting ice sheet will have negative impacts on communities across Greenland, especially in northern settlements such as Qaanaaq where permafrost melting is destabilising homes and roads and impacting how fishers and hunters operate.

But her real concern lies on the impact it will have globally. “I am not so scared of what the effects of the melting of ice in Greenland will be,” Frederiksen says, “It scares me what effect it can have for the rest of the world.”

After school, Frederiksen volunteers with Greenland4Nature, a collection of young Greenlandic people trying to make their voices heard about climate change. But she says it is hard to remain hopeful. “When this world shows me how people deal with CO2 emission, pollution of the ocean, pollution of the soil … I get scared.”

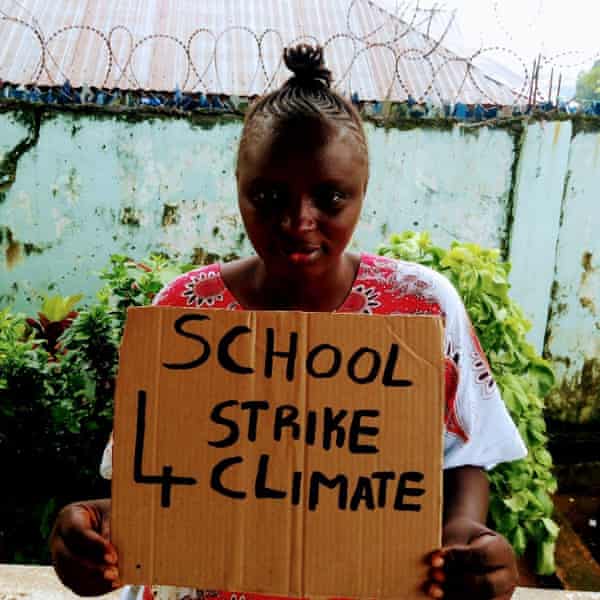

Roseline Mansaray, 26, Freetown, Sierra Leone

Roseline Mansaray has not slept in weeks. It is the rainy season in Freetown, Sierra Leone and she is scared. “I am in panic, praying for my country not to experience any more destructive flooding this year,” she says.

West Africa is one of the few places in the world that experiences monsoons. But as the planet heats up, the monsoon patterns are changing, potentially leading to either significant increases or decreases in rainfall.

“Some models say it will get wetter, others say it will get drier,” says Prof Lenton. “But either way would be problematic.”

Already, Mansaray has watched increased rainfall during monsoon season devastate her community. She used to live in Kroo Bay, an informal housing settlement where floods destroyed homes in her community, injured her neighbours, contaminated drinking water and led to the spread of waterborne diseases including cholera, diarrhoea and typhoid.

Then on 14 August 2017, Mansaray witnessed a hillside collapse after heavy rains that killed an estimated 1,000 people and displaced hundreds of families who were moved into temporary camps.

Mansaray is doing her part to address the climate crisis: she is one of the main organisers for Friday for Futures in Sierra Leone, planning local street protests as well as helping organise some internationally. For her, activism is less a choice than a matter of survival.

“I am no stranger to climate change,” she says. “I have tasted its bitterness.”