What is deforestation – and is stopping it really possible?

As world leaders prepare to commit to halting the destruction of forests, here’s everything you need to know about some of the planet’s most biodiverse places

Last modified on Mon 1 Nov 2021 15.12 EDT

Forests and nature are centre stage at Cop26. On the second day of the Glasgow summit, world leaders are expected to announce a commitment to halting and reversing deforestation. As the second largest source of greenhouse gases after energy, the land sector accounts for 25% of global emissions, with deforestation and forest degradation contributing to half of this.

But why do forests matter to the climate, and how can we halt deforestation?

What is a forest?

There are an estimated three trillion trees on Earth. Some form part of enormous forest ecosystems like the Congo rainforest, while others stand in sparsely populated landscapes such as on the edges of the Sahara desert. Of the 60,000 known tree species, nearly a third are threatened with extinction, according to a recent assessment.

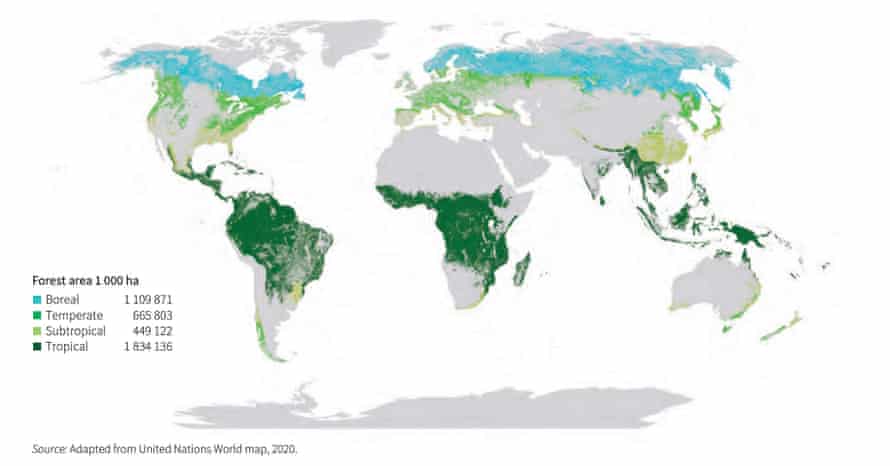

Scientists cannot decide on a single definition of a forest due to disagreements over tree density, height and canopy cover. But the Food and Agriculture Organization’s version is commonly used: “Land with a tree canopy cover of more than 10% and area of more than 0.5 hectares.” Forest covered almost a third of the world’s landmass in 2020, with more than half found in just five countries: Russia, Brazil, Canada, the US and China. The taiga – also known as northern boreal forest – is the world’s largest, stretching around the northern hemisphere through Siberia, Canada and Scandinavia.

Temperate, tropical and boreal are the three main types of forest that include a great diversity of ecosystems: cloud forest, rainforest, mangrove swamps, and tropical dry forest, among many others.

Why do forests matter for the climate?

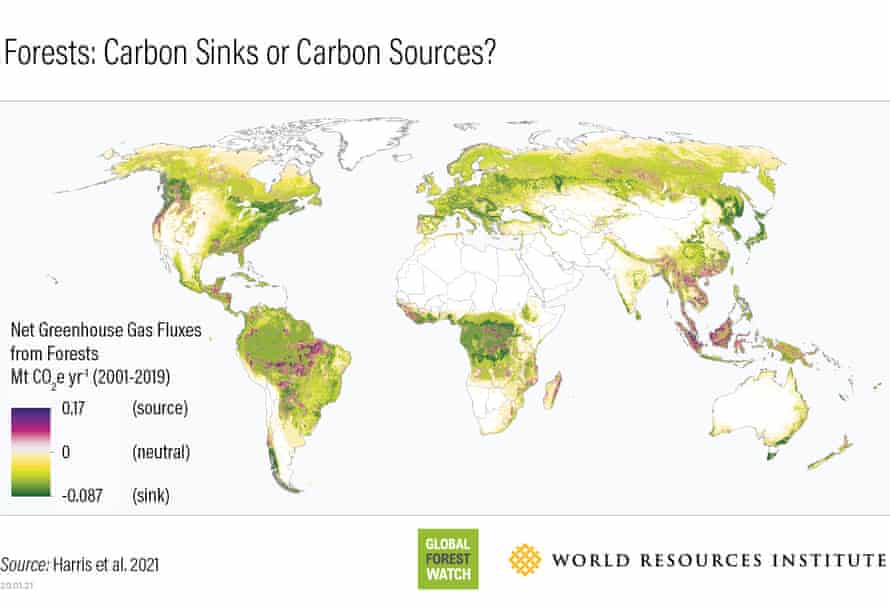

Forests are among the most biodiverse places on the planet and form an enormous carbon store, regulating the world’s weather and climate. They hold about 861 gigatons of carbon – equivalent to nearly a century’s worth of annual fossil fuel emissions at the current rate – and absorbed twice as much carbon as they emitted in the last two decades. More carbon is stored in soil (44%) than living biomass (42%), with the rest found in dead wood (8%) and forest litter (5%). Forests like the Congo basin rainforest – the world’s second largest – affect rainfall thousands of miles away around the Nile. Billions of humans rely on forests for food, building materials and shelter.

But they are being cleared at a relentless pace. About 10% of tree cover has been lost since 2000, according to Global Forest Watch. Although estimates vary, the land sector is the second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions and accounts for around a quarter of emissions, according to the IPCC, of which deforestation is a major component. Many scientists say it will not be possible to limit global heating to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels without halting deforestation.

“There are two main points on forests and carbon,” says Yadvinder Malhi, a professor of ecosystem science at the University of Oxford. “Forests are a carbon store, meaning that when you deforest, you’re releasing CO2 into the atmosphere. The other thing is that intact forests have been shown to be a carbon sink, absorbing carbon over time. And if our sink is disappearing, you’re losing the service that the biosphere provides – an assumption that such a sink will continue is built into almost all of our climate model scenarios for this century.”

Do all forests store the same amount of carbon?

No. Old-growth forests that are free from human industrial interference and pollution are especially important for the climate and biodiversity. They are called primary forests and are ancient, carbon-dense ecosystems bursting with life such as parts of the Amazon, the Bialowieza Forest in Poland and Papua New Guinea. With some of the largest trees and the biggest variety of life, conservationists place extra emphasis on their protection from logging, wildfires and human industry as they only account for one-third of the planet’s forest cover. Young or recovering forests store much less carbon and can sometimes take several years before they become effective sinks.

Tropical rainforests, mangrove and peat swamp forests – such as those found in south-east Asia – play a disproportionally important role in regulating the climate due to the amount of carbon they store, their cooling effect and the protection they provide from flooding. Boreal forests, which are covered in snow for large parts of the year, reflect more heat back into the atmosphere and have a net warming effect on the climate. Agricultural tree plantations with very few species are much less carbon-dense and support much less life.

What is deforestation?

Deforestation is the human-driven conversion to another land use of a forest, such as cattle ranching or soya bean production, that is often clearcut with machinery then burnt. It is not the same as logging: trees can be selectively taken out of a standing forest. Deforestation has gone hand in hand with human development for centuries. Nearly all the temperate rainforest that once covered large parts of the British Isles was cleared for agriculture, roads and human settlements, for example.

As well as being a major source of carbon emissions, land use change is the primary driver of biodiversity loss, which scientists warn is driving the sixth mass extinction of life on Earth. From space, deforestation often follows a “fishbone pattern” where land is cleared along the edges of roads and rivers. Over time, the fishbone fills in as more of the forest is cleared. On a large scale, the process can become self-perpetuating, such as the Amazon switching from rainforest to savannah, as so much of it has been destroyed.

Last year, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bolivia, Indonesia and Peru were the top five countries for tropical primary forest loss. About 12m hectares (30m acres) of tree cover was lost in the tropics. This includes 4.2m hectares of primary forests, an area the size of the Netherlands, releasing the equivalent to the annual emissions of 570m cars.

Why do people clear forests?

While there are many local factors, experts say the main reason is financial: forests are worth more dead than alive in monetary terms. In Brazil, large parts of the Amazon have been cleared for beef production. In Indonesia, forests and peatlands have been cleared and drained for oil palm plantations. In other areas, coffee, cocoa, bananas, pineapples, coca leaves and subsistence farming have driven land-clearing. Most deforestation hotspots are in tropical regions, which are also profitable areas for farming.

“The largest factor is the expansion of agricultural industries: cattle ranching, soya bean farming and oil palm,” says Malhi. “A second factor is poverty. In many parts of Africa, such as Madagascar, where there is demographic pressure, a lot of poor, rural settlers are just looking to make a living on the frontier as populations increase. The same is true in parts of South America and south-east Asia.”

Can we really stop deforestation?

It will not be easy, but there are reasons to be hopeful. Alongside the commitment from world leaders in Glasgow at Cop26, it is hoped big producers and consumers of commodities linked to deforestation will sign up to eradicating them from the global supply chain. China – one of the world’s largest consumers – is taking deforestation more seriously and is looking at “greening” its supply chain.

“We really need to start thinking about forest loss – especially tropical forest loss – in the same way people are now talking about coal,” says Frances Seymour, a forest and governance expert at the World Resources Institute (WRI). “There was a big celebration that China had committed to no longer financing new coal abroad. But we need to be looking for similar commitments from all countries to stop financing projects that lead to deforestation abroad.”

Are there any examples we can learn from?

Costa Rica is the only tropical country to successfully halt and reverse deforestation. It did so, in part, with payments from an ecosystem services programme that put an economic value on standing forests and biodiversity. The country won the first Earthshot prize this year for the scheme, reversing one of the highest deforestation rates in Latin America in the 70s and regrowing large areas of forest.

On a larger scale, Brazil had considerable success at reducing deforestation in the Amazon in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Environmental laws, improved surveillance of slash-and-burn illegal logging and a soya moratorium in the Amazon were credited with the fall. However, there have since been large spikes in deforestation in the world’s largest rainforest under the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro. Indonesia has had success in recent years slowing deforestation with a palm oil expansion moratorium, although experts warn it is fragile for the same reasons: the economic incentives to clear forest have not changed.

A UN scheme that provides financial incentives to protect forests – known as Redd+ – has been agreed by countries. It allows developing countries to sell carbon credits to preserve carbon sinks. Although there is still division over the rules for carbon markets, it is hoped these will be sorted at Cop26. Countries like Gabon, with low deforestation rates and large forest cover, say that they also need funding to protect forests. Gabon is the chair of the African group of negotiators for Cop26.

Why are indigenous communities so important for stopping deforestation?

Studies show indigenous communities are the best protectors of forests. Many landscapes thought to be wilderness have actually been managed by indigenous communities for centuries. This year, a UN review of more than 250 studies found that in Latin America, deforestation rates were lower in their territories than elsewhere. Despite this, many indigenous and tribal peoples face persecution, racism and violence.

In July, a two-year trial using remote sensors to alert indigenous communities in Peru to early deforestation found a decrease in tree loss of 37% overall for both years, compared to the control group. Researchers say that if this was scaled up, it could have a big effect on reducing deforestation.

Jessica Webb, senior manager for global engagement at Global Forest Watch, says: “A third of the Amazon rainforest falls within approximately 3,300 formally acknowledged territories of indigenous peoples. Based on modelling we did with our partner Rainforest Foundation US, as a result of this study, we predict that an additional 123,000 hectares a year of deforestation could be prevented by scaling this approach to other communities within the Amazon. It would be the equivalent of taking 21m cars off the road for a year.”

Can satellites protect forests?

Ecosystem monitoring is experiencing a technological revolution. Deforestation is easier to track through a dataset developed by researchers at the University of Maryland, Nasa and Google. As image resolutions improve, we are close to being able to monitor deforestation in real time.

But “there are still gaps on being able to monitor restoration and degradation”, says Crystal Davis, director at the Land & Carbon Lab, a WRI initiative that aims to provide information on how the world can meet climate and biodiversity commitments and the needs of 10 billion humans. “We also need a better understanding of the accuracy of global datasets. They are not consistent across geography,” she says.

What about reforestation?

The world needs to restore forests to meet climate and biodiversity goals. But scientists say halting deforestation is an urgent task as it emits carbon immediately whereas it takes decades for nature to recover and sequester carbon. Primary forests that have stood for thousands of years cannot be replaced by tree-planting schemes.

What if we don’t stop deforestation?

Cutting emissions from fossil fuels is the most urgent task to avoid more global heating. But if the world continues to lose forests, we risk triggering tipping points with unintended consequences. The Amazon could turn into savannah, boreal forests could die back and carbon stores that took thousands of years to sequester could be released. What this would mean for food security, weather systems and millions of other species is unlikely to be good news, experts warn.

Robert Nasi, head of the Center for International Forestry Research, says: “We would have climatic change that is cascading: the drying of the Amazon, the Congo Basin … there is a lot of risk of a domino effect. If we don’t protect the forests, people will migrate, there will be climate refugees.”

With thanks to:

Crystal Davis, director at the Land & Carbon Lab

Frances Seymour, distinguished senior fellow, World Resources Institute

Luiz Amaral, director, global solutions for commodities and finance, World Resources Institute

Robert Nasi, director general at the Center for International Forestry Research

Yadvinder Malhi, professor of ecosystem science at the University of Oxford

Jessica Webb, senior manager for global engagement at Global Forest Watch