Laramba’s Indigenous residents fear they are at risk of long-term illness and say they need to know who is responsible for fixing the problem

Jack Cool is looking to hitch a lift out of town.

The 71-year-old former stockman has lived in Laramba, a remote Indigenous community in the Northern Territory, for most of his life.

Since his partner, Jennifer, 57, and his youngest daughter, Petrina, 35, started kidney dialysis at the end of last year, he has been trying to make the two-and-a-half hour trip south into Alice Springs whenever he can.

Cool, who also takes medication for kidney issues, says he doesn’t know why this has happened to his family but he thinks it has something to do with the water.

“When we drink the water it makes us sick,” he says.

Problems with Laramba’s water supply have been known since at least 2008 but the scale of the issue was not revealed until 2018, when testing by the government-owned utility company Power and Water Corporation (PWC) found drinking water in the community of 350 people was contaminated with concentrations of uranium at 0.046mg/L.

That is nearly three times the limit of 0.017mg/L recommended in the Australian drinking water guidelines published by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Follow-up testing in 2020 found the problem was getting worse as uranium concentrations – which occur naturally in the area – had risen to 0.052mg/L, and the water also contained contaminants such as nitrate and silica.

A stream of conflicting advice

Prof Paul Lawton, a kidney specialist with the Menzies School of Health Research who has been working in the Territory since 1999, says there is no good evidence to say for sure whether the water at Laramba is safe to drink.

Lawton says the Australian drinking water guidelines are based on “pretty tenuous evidence” from rat studies, but the lack of evidence cuts both ways.

“There is a plausible theory, shared by many in the medical community that heavy metals coming from bore water may cause problems with, in particular, the kidneys,” he says. “But this is not likely to be a short term risk but a longer term risk.”

Assoc Prof Tilman Ruff from the Nossal Institute for Global Health at the University of Melbourne says uranium contamination also delivers “relatively low but relatively frequent doses” of radiation.

“The overall consequences from a radioactive point of view is that this will widely dispose in the body and organs, and will contribute to a long-term risk of cancer,” Ruff says.

Because children are particularly vulnerable, with girls 40 times more likely than boys to be affected over their lifetime, Ruff says there is “no good amount of radiation”.

Though there are still many unknowns, authorities elsewhere have addressed similar situations by acting with caution. In Eton, Queensland, a bore supplying the community was turned off when concerning concentrations of uranium were found in the water supply.

In June 2018 PWC’s general manager of remote operations, David Coucill, told a Senate estimates hearing the corporation planned to treat the water to deal with the long-term risk but the contaminant was “not at levels that concern us in the near term”.

“The water is perfectly safe to drink today,” Coucill said.

“You can drink the water today; you could drink the water next year. It is not going to hurt you in that time frame, but if you are going to stay there forever, we need to at some stage move to water treatment of that aquifer. That is the plan.”

The former minister for essential services Dale Wakefield told the ABC in 2020 that the risk to human health was minimal.

“The Department of Health has said, whilst [contamination levels] are over the World Health Organization guidelines, there is no immediate threat to people’s health and wellbeing,” Wakefield said. “There are no studies to show water at that level will impact people’s health.”

Asked whether there had been any update, NT Health said its “assessment of the health risk associated with drinking the water at Laramba has not changed in the last 18 months.”

‘A permanent holding pattern’

Laramba is just one of many among the 72 remote Indigenous communities in the Territory whose water is contaminated with bacteria or heavy metals.

This year the NT government promised $28m over four years to find “tailored” solutions for 10 towns, including Laramba, after a campaign by four land councils for laws to guarantee safe drinking water across the territory.

Asked what was being done to fix the problem, a spokesperson for PWC directed Guardian Australia to sections of the company’s latest drinking water quality report that discuss pilot programs for “new and emerging” technologies to “potentially” clean water of uranium and other heavy metals.

But Ron Hagan and Stephen Briscoe, both senior men within Laramba, say the community has been kept in the dark.

“No one told us anything,” Briscoe says. “They were keeping things really quiet. No one came to tell us about the water.”

What little information that is available has filtered through in the media or highly technical language that many people, for whom English is a second language, can’t understand.

In the meantime both men say several people, including some in their own families, have been diagnosed with kidney problems or cancer.

“We have to drink, so we are drinking it,” Hagan says. “We don’t know anything about $28m. We’re still here drinking the same water. Nothing’s changed.”

The co-director of the Environment Centre NT, Kirsty Howey, says communities such as Laramba have been left in a “permanent holding pattern” and the lack of engagement is a “feature of a flawed system”.

“We have these ad hoc promises for funding infrastructure depending on what’s in the government coffers at a particular time,” Howey says. “This doesn’t address, in a structural way, the underlying causes of drinking water insecurity in remote communities.”

The persistence of the problem for so long owes much to the opaque and confusing way water is supplied to remote Indigenous communities.

There are no laws regulating water quality outside 18 gazetted townships and it is not clear who holds responsibility.

The actual work of installing, maintaining or upgrading any infrastructure is handled by a wholly owned subsidiary of PWC called Indigenous Essential Services. IES is officially a separate entity, and draws its operational funding from government grants, but it has no shopfront, no independent offices and no staff.

PWC is advised on water quality by NT Health, but a spokesperson for NT Health said responsibility for managing water infrastructure “does not sit within NT Health”, and directed questions to the Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Logistics.

Then there is the role the NT government plays as landlord.

Because the government owns many houses in Laramba, residents attempted to take it to the NT civil and administrative tribunal in an attempt to force the installation of reverse osmosis filters on their taps.

But in July 2020 a tribunal decision found landlords had no responsibility for the water supply to their properties.

Boiling point

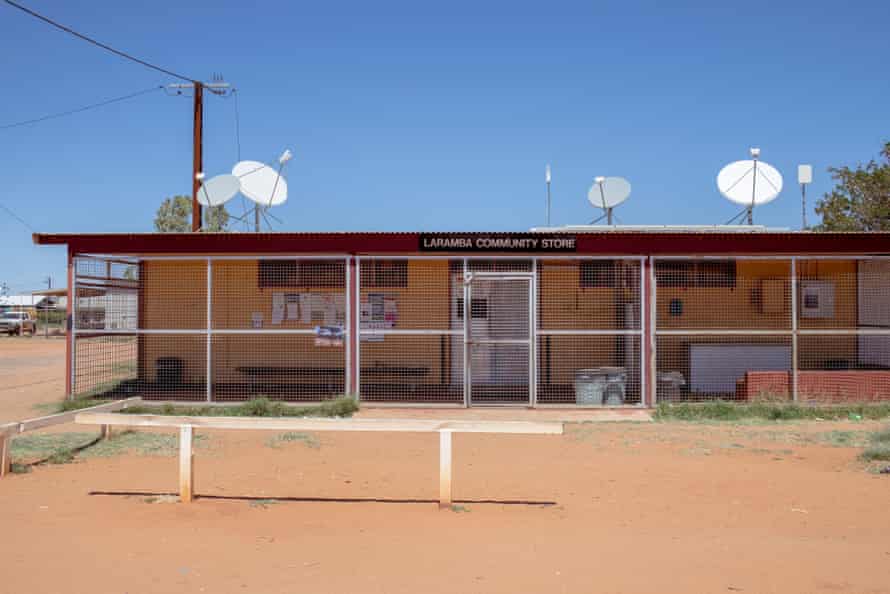

Andy Attack, a non-Indigenous man who runs the Laramba general store, says in the three years he has lived there he has noticed a change in the community.

“People here are just so respectful and polite and calm,” he says. “The water is something that makes them really angry, and they don’t like being angry. It’s not nice seeing them like that.”

Attack says the first thing he was told when he moved to Laramba was not to drink the water. He installed reverse osmosis filters normally used in hospitals, which cost $130 a year to maintain, on the taps in his house.

Those who can’t afford such sums must either rely on rainwater or buy expensive 10L casks. Attack says the only distributor in the region who will deliver to Laramba charges $8.50 a box wholesale for items that would retail for $3.50 in Alice Springs.

“The way I feel, personally, is that these people are entitled to having clean drinking water coming out of their taps,” he says. “And they’re not getting it. It ain’t right. Laramba deserves better.”