Coal-state Democrat set to scupper Biden clean energy plans

White House forced to rewrite domestic bill as it makes late bid to secure backing for international deal

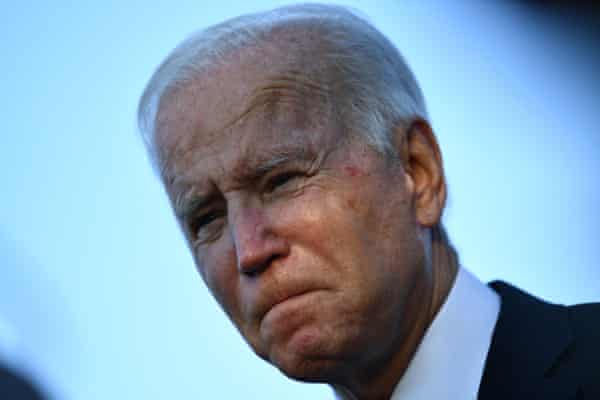

President Joe Biden is likely to abandon a clean energy programme that was the centrepiece of his efforts to tackle greenhouse gas emissions at home, US media reported, because of opposition from a swing-vote Democratic senator from a state with a historically large coal industry.

Funding to replace coal- and gas-fired plants with wind, solar and nuclear generation was part of a massive budget bill that Biden is struggling to get through Congress.

The New York Times reported that White House staff members are now rewriting the legislation without the $150bn clean energy provision, on the expectation that they will not be able to pass the original version because of staunch opposition from the West Virginia senator Joe Manchin.

The news is the latest blow to hopes for the United Nations summit on climate change, Cop26, due to be held in Glasgow in two weeks’ time.

China, the world’s top emitter of greenhouse gases, last week revealed plans to build more coal-fired power plants, and hinted it may be rethinking its timetable to cut emissions, as it struggles with an energy crisis amid slowing economic growth.

It also seems increasingly clear that President Xi Jinping, China’s most powerful leader in many years, will not attend the Cop26 gathering. His absence will undermine hopes that dealmaking could get extra impetus from a personal gathering of leaders.

For the Glasgow summit, which has been delayed by a year because of the pandemic, countries are expected to produce revised national emissions-cutting targets to help the world limit heating to 1.5C, the legally binding goal of the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

The UK presidency also hopes to focus on three other areas to meet climate goals: climate finance, phasing out coal, and nature-based solutions.

Scientists estimate that emissions must be reduced by 45% by 2030, compared with 2010 levels, and from there to net zero emissions by 2050, if the world is to have a good chance of remaining within the threshold agreed in Paris.

The UK and other major players have already accepted that they will not be able to win commitments for such sweeping cuts from big emitters at Glasgow, so instead London is focused on making enough progress to “keep 1.5C alive” as a potential goal.

British diplomats say they are “cautiously optimistic” about overall progress, with a deal on providing $100bn to developing countries expected to be sealed and some advances on an agreement to halt deforestation and the destruction of nature. Last week more than 20 countries joined a pledge to cut methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

The UK, the US and the EU have also embarked on a frantic round of climate diplomacy in a last-ditch attempt to bring key countries into a deal.

But the latest news from the US and China, the world’s top emitters of greenhouse gases, will raise questions about how much progress the meeting can make towards core emissions goals.

America is historically the world’s largest producer of greenhouse gasses and the US clean energy project was set to be the cornerstone of American efforts at Glasgow to push other countries to move faster on tackling climate change. Biden has called for urgent action on climate, in a definitive break with his predecessor Donald Trump, who rejected the international scientific consensus on a world heating up, and hobbled global efforts to do something about it.

But if the president is forced to abandon the clean energy provision, it may damage international faith in Washington’s ability to turn rhetoric into domestic action on climate change. It would certainly make it harder for climate envoy John Kerry and his team to push other countries to make costly efforts to cut their own emissions.

The electricity sector produces about a quarter of US greenhouse gases, and the infrastructure programme was meant to trigger a long-term shift in the country’s energy sector that would endure beyond Biden’s presidency.

It proposed incentives for utilities to clean up their energy production and penalties for remaining reliant on fossil fuels.

Manchin, who has said he strongly opposes the clean energy deal, has personal financial ties to the coal industry and represents a state where mining, although shrinking, still employs thousands of people.