Britain’s leaky homes make the energy crisis worse. Why have governments not fixed them?

Our housing stock needs better insulation and low-carbon heating, or we’ll continue to suffer these shocks

Over the past few days the country has been thrown into panic, as soaring gas prices threaten to plunge hundreds of thousands more households into fuel poverty, joining the 2.5 million already there. For others, uncomfortably tight budgets will be further squeezed. Any country reliant on the worldwide gas market faces the risk of perennial price shocks. But let’s be clear: the extent of this crisis was not inevitable. It is, in significant part, the result of a decade of government failure to insulate us from the disastrous downsides of fossil-fuel dependency.

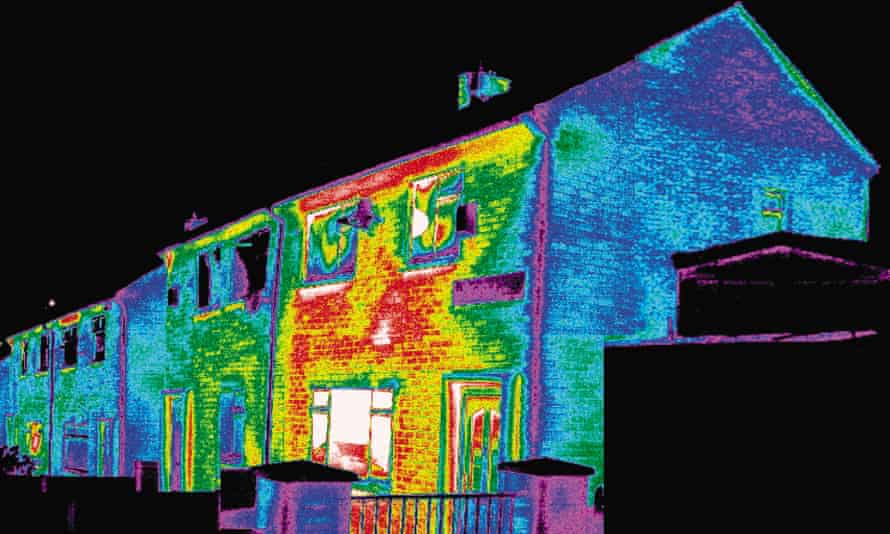

The UK is a difficult country to keep warm. It has some of the oldest and leakiest housing stock in western Europe, ensuring that heat dissipates through walls, windows and doors quickly after leaving radiators. Nine in 10 households rely on gas boilers, and lots of gas boilers need lots of gas: UK households consume more of it than almost all of their European peers, at around twice the EU average. In 2000, when North Sea gas accounted for 98% of overall supply, households were at little risk of price shocks. But as national production has tumbled by two-thirds in the two decades since, imports have risen from just 2% to 60% of supply to fill the gap.

Gas burned in households now equates to half of all imports – that is why any spike in gas prices immediately translates into higher heating bills. In times like these there is little standing between the average household and the opaque mechanics of a deeply politicised, and profit-driven, global gas market. Using cheap gas to compensate for poor housing stock only works as long as gas is cheap – and as long as you don’t have a climate crisis spinning out of control.

Given all this, you’d be forgiven for thinking the government might have made it a national priority in recent years to reduce our entrenched reliance on fossil gas. While a significant task, a well-designed programme to repair the nation’s homes should not have been beyond us. It’s Rockwool insulation, not rocket science. Instead, we have witnessed a decade of half measures and outright failure.

In 2013 the Tory-led coalition launched the “green deal”. Intended to be cost-free for government, it offered loans – with interest – to householders to install efficiency measures, repayable via the household’s energy bills. Unsurprisingly, the complexity of the scheme combined with its inherent financial uncertainty did not lead to strong takeup. Of a target of 14m insulated households by 2020 just 15,000 had been completed when the programme was binned a couple of years later.

Next, the zero carbon homes standard, which had been due to come into effect in 2016, would have required new homes to generate as much energy on-site from renewable sources as they used – it was a flagship policy genuinely worth the hype. Instead, soon after the surprise 2015 Conservative election win, George Osborne killed the programme at the behest of the construction lobby. It has never been revived.

Then came the green homes grant, announced in one of the first Covid economic stimulus packages last year. This was a simpler scheme, with upfront government grants. And yet, despite very high levels of public interest and applications to the scheme, it reached only 5,800 of its target 600,000 homes – a select committee investigation called its implementation “botched” and its administration “disastrous”. Like the green deal nearly a decade ago, it was cancelled early.

The sum total of this is not pretty. Between 2012 and 2019 the number of home insulation installations actually dropped by 95%. The charity National Energy Action has noted that at that rate it would take nearly a century to properly insulate all of the current fuel-poor homes in the country. In 2021, millions still live in fuel poverty, and many more will likely join them this winter, while domestic gas boilers account for one in seven tonnes of carbon the UK emits each year, accelerating the climate crisis.

This must be the last winter fuel crisis we ever face, and our homes must be future-proofed without delay. Ministers are already more than a year late on delivering plans for how to end burning gas for heat. They must deliver a credible plan immediately. Only an ambitious, long-term, well-funded and properly designed national retrofit scheme will do.

Even further than this, it is well past the time to bid farewell to gas boilers altogether. No new builds should be connected to gas, and every time a boiler breaks, with a handful of exceptions, it should be replaced by a heat pump – an ultra-efficient device that uses electricity to harvest ambient heat from the air (or ground) to heat your home. The UK props up the table of European countries for annual installations: Lithuania installs five times as many per year as we do, Italy 10 and Norway 60.

At the current rate it will take the UK around 700 years to move to low-carbon heating. The government’s legally enshrined climate commitments require us to be halfway there by the mid 2030s. The good news is the public are increasingly warming up to change: polling by researchers at Walnut Unlimited in June found that more than two-thirds of people agreed that homes should switch to a low-carbon heat source. Like solar panels, the more that are installed the more we’ll learn – and the cheaper they will get.

This task is ambitious, but also entirely achievable. To succeed, we must learn from our mistakes – and the success of others. Whether this government does so will be a deciding factor in whether we will find ourselves again at the mercy of the markets as the winter nights draw in.

-

Max Wakefield is director of campaigns for the climate action group Possible