An encounter with a wedge-tailed eagle filled me with awe and a sense of danger

Birdwatching reminds Georgia Angus of the importance of appreciating our non-human co-inhabitants of this big spinning rock

The Guardian/BirdLife Australia 2021 bird of the year poll begins on Monday

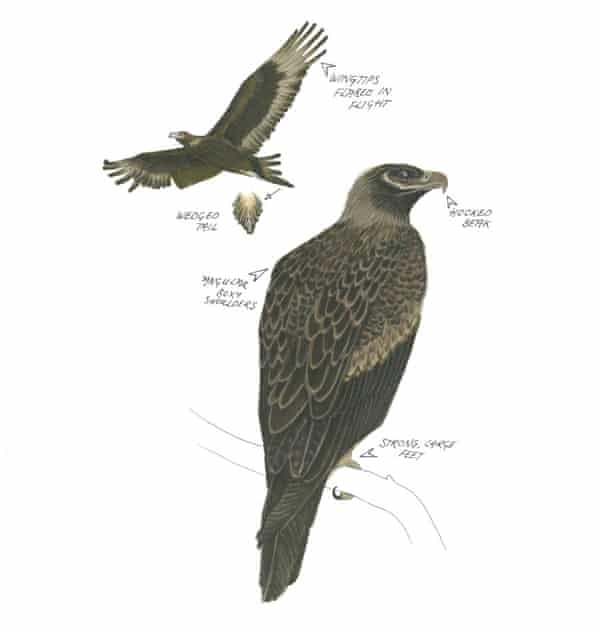

Over the past few years, my amateur bird watching has escalated into more of an obsession, one that occasionally pulls me out to more remote areas of Australia. Several months ago on one such trip, I had cause to think about what drew me to birds. On that particular day, I was walking in the Warrumbungles in New South Wales, trekking up a slope toward Mt Exmouth. I rounded a corner to spot an enormous wedge-tailed eagle perched on the ridge above me. It was an adult, with dark, near-black plumage, boxy shoulders and an immense beak. Its sheer mass was striking.

I looked at the eagle. And the eagle looked at me. Then, finding my sweaty human form unimpressive, it turned its head to inspect the view instead.

I, however, was more than impressed. And a little nervous. I knew that this bird had a wingspan of nearly three meters. The talons were gloriously large. I imagined those feet could crush a melon without batting a feather. Even though wedge-tailed eagles largely subsist on rabbits and carrion, and no records exist of them attacking humans in the wild, some prehistoric part of my brain was uneasy seeing something that big and fierce-looking up close. Tangled up with this feeling of awe was, of course, wonder, but there was something else too. A sense of disquiet upon seeing the eagle.

My happiness at seeing this bird was tinged with a deeper concern that this eagle was in danger, just as much as any other native animal that is clinging on to diminishing land reserves. Over the last several years, there has been a spate of eagle poisonings across Victoria. Some landowners, misinformed about the behaviour of wedge-tailed eagles, poison the birds to ‘protect’ their livestock. They do it by injecting pesticides into the carcasses of dead lambs. The eagles that eat from a poisoned carcass die within thirty minutes. There have been raids where authorities uncovered masses of eagle carcasses on properties (400 eagle corpses were found in one case).

Maybe these people genuinely fear the advance of predatory birds on their livestock. Or maybe they are unconsciously repeating our historical battle of wills with the landscape, pushing back and destroying that which we don’t understand. Either way, these killings highlight the essential failure of understanding between humans and other animals that we share the landscape with. This is what makes bird watching important. We are seeing and trying – even if we often fall short of the mark – to understand these animals, and their role in the ecosystem. Knowing animals, be it birds, bats, quolls or koalas, allows us to properly appreciate their strangeness, their uniqueness, and empowers us to protect them.

Zoom back to the Warrumbungles. I stood in rapture as the eagle surveyed the landscape. It was beautiful, powerful and immense. I was a little scared of it, but even moreso, I was scared for it – scared that something so big and strong and seemingly above the daily humdrum of humans could be rendered so vulnerable. Most of all, I was grateful for the reminder of how much we need to appreciate our non-human co-inhabitants of this big spinning rock.

In writing 100 Australian Birds, it was this appreciation that drove my late-night illustration sprees, drawing whistlers, kites and quail, long days of writing and labyrinthine phone calls with passionate birdwatchers.

Birdwatchers, alongside other naturalists, are a special kind of obsessed. If you have an obscure question about gang-gang cockatoos that your first contact doesn’t know the answer to, they’ll know the name of someone who does. Birds, noticing them, discussing them, recalling stories of them, and, finally, their absence, is what creates communities of people that care about these animals and drives them to advocate on their behalf. Maybe it only starts with a favourite species for an individual person, but that is a powerful catalyst.

Whether we roadtrip to the northern coast in search of the elusive Carpentarian grasswren, or simply note from the kitchen window that the young magpies are particularly demanding this spring, birds are a way for all of us to connect. My neighbours might think I’m a bit loopy when I freeze for minutes on the side of the road, smiling inanely as I stare into a peppermint gum (it was full of spotted pardalotes), or when I emerge from a hedge with twigs in my hair, in pursuit of a flock of silvereyes. The reason I pause to watch birds is because they are part of a bigger network of understanding about the environment. It’s right there for you to start connecting with if you only take the time to notice it.