Dancing, starry dwarf and narrow-mouthed: new species make India a frog paradise

Dozens of discoveries in recent years have shown the country to be a treasure trove of amphibians

Last modified on Tue 21 Sep 2021 02.02 EDT

It is barely the size of a thumbnail, so it may not come as a surprise that it took so long to spot the starry dwarf frog. It was discovered sitting next to some leaf litter by eagle-eyed researchers on a joint US-Indian expedition in thick shola forest in the Western Ghats in Kerala, south India, during a nocturnal hunt.

The starry dwarf frog, or Astrobatrachus kurichiyana, named after a tribe in Wayanad, Kerala, where the frog was found in 2019, is just one of dozens of new species found in recent years that have revealed India to be a frog paradise.

In the same year, a new species of narrow-mouthed frog, commonly called rice frogs, was found in an evergreen forest in a tiger reserve in Arunachal Pradesh, in India’s far east. The following year, three new horned frogs were found in the forests of north-east India.

In the last 10 years, 14 new species of dancing frogs – tiny acrobatic frogs that attract their mates with unique kicks and seven new night frogs – some as small as a coin – have also been found in the Western Ghats.

Amphibians have been around for millions of years and are the most threatened class of vertebrates. There are more than 6,759 species of amphibians worldwide, of which India has more than 440 species – up from 238 since the start of the new millennium.

Although the amphibian population has been declining around the world – the IUCN Red List estimates that 41% of amphibians are threatened with extinction – in India many new species are being discovered. But many face extinction threats due to loss of habitat from the building of roads, human settlements and the felling of trees, as well as diseases such as fungus.

Amphibians have porous and permeable skin and because they spend a portion of their life cycle in water and on land they are sensitive to environmental stressors and pollution. Frogs are important bioindicators and barometers of climate change, and even subtle changes in moisture or temperatures can have a drastic impact on their populations.

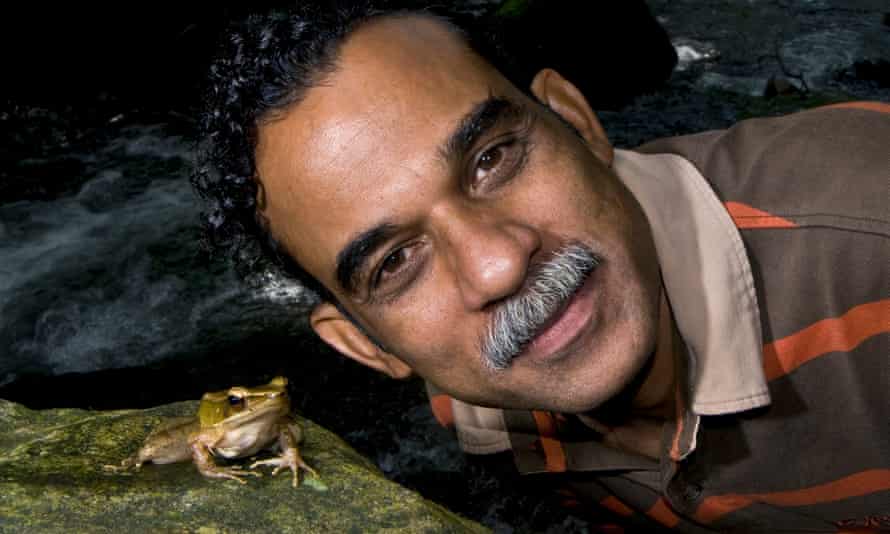

Sathyabhama Das Biju, an amphibian biologist and wildlife conservationist at the University of Delhi, is called “India’s frogman”. He has worked since 1990, first in the Western Ghats and then in north-east India, discovering more than 100 new species of frogs, including the rare purple frog in Kerala, which remains underground all year, except for two to three weeks in the mating season.

In 2010, Biju launched the Lost Amphibians of India, a project collaborating with other institutions to rediscover species thought to have become extinct. “This citizen science project helps in rediscovering amphibians, with 17 groups of Indian citizens, from schoolchildren to engineers, working under scientists and has rediscovered as many as 29 species, some sighted after a century,” he says. “Frogs are everywhere and we have discovered new species even in roadside puddles near large towns,” he adds.

“The frogs have an evolutionary history of 350m years and many species may look the same but are genetically distinct and therefore called cryptic species,” says Dr K P Dinesh, a scientist with the Zoological Survey of India ( ZSI), Pune.

Dinesh has worked with amphibians, especially frogs, since 2000, and has discovered more than 50 species. “More than 90% of the frogs found in the Western Ghats are endemic to the region and cannot be found anywhere else in the world,” he says.

The Western Ghats is one of 36 recognised biodiversity hotspots around the world and a Unesco world heritage site, with special microclimates, habitats and unique ecosystems and a high percentage of flora and fauna that can’t be found elsewhere. Rare species have been found here, such as the purple frog, which is believed to have coexisted with the dinosaurs, and was discovered only in 2003. Its closest relatives are in Seychelles in the Indian Ocean.

“North-east India is another treasure trove of new species. This part of the country is relatively unexplored, unlike the Western Ghats, and many exciting discoveries in the future will be from here,” says Biju.

KS Seshadri, an evolutionary biologist from the Indian Institute of Science, found three new species of narrow-mouthed frogs in 2016, near the coastal city of Mangalore. “It’s unfortunate that ancient laterite rock formations in India are classified as wastelands and mined for bricks, and not protected, because that was where we found new species of frogs,” he says. Seshadri has also done some pioneering work on measuring the effect of climate change on frogs, by recording their calls and correlating them with weather at different points in time.

“Frogs are hard to study. Many frogs are nocturnal and very challenging to sight, as they live in fast-flowing streams and forest ground and come out only when it’s dark. Though it’s exciting to find new species, there’s a lot of hard research and months of lab work that is behind it. It’s hard to obtain research permits in forests to study them,” says Seshadri.

But as technology has advanced, more species have been discovered. “With new techniques like molecular genetics and DNA analysis, we are better equipped to classify cryptic species,” says Seshadri. “Also, researchers are probably just looking more carefully at species that were last described in British [rule] times.”

NA Aravind Madhyastha, a biologist who works with the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (Atree), Bengalaru, says: “A better understanding of taxonomy coupled with using more morphological characters, as well as acoustic parameters like their calls, and molecular and DNA testing has led to a spate of rediscoveries and discovery of new species.”

One of Madhyastha’s most fascinating finds was in a timber yard in Mangalore on India’s western coast – a narrow-mouthed frog called Microhyla kodial, whose closest relative is found only in Myanmar. “The research indicated that the frog could have been accidentally introduced with timber imported from Malaysia, Indonesia and Myanmar, he says.

Biju is certain there are many more frog species to find in India. “Most of our country’s conservation efforts are aimed at the larger, more charismatic animals, and smaller creatures like frogs are not considered important enough for funding and research grants,” he says. “That has to change.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features