Two decades ago Richard Stiles escaped an avalanche in New Zealand, but friend Steve Robinson wasn’t so lucky. Now the mountain has given up some of its secrets

When mountaineer Chris Hill found a backpack with an old camera in it on the Hooker Glacier – an 11km chunk of ice on New Zealand’s South Island – he was intrigued and decided to get the film inside developed.

Hooker is at the base of Aoraki (Mount Cook), in a national park of icy peaks where hundreds of climbers have died, dozens of them never to be found.

Hill wanted to know whose pack he held, so he took the photos – grainy and vintage-looking – to the police and to New Zealand’s Land Search and Rescue. Eventually, he posted them on Facebook, hoping the mountaineering community could solve the mystery of the pack and the camera.

The photos were shared and finally the mystery was solved. The mountain had given up one of its many secrets.

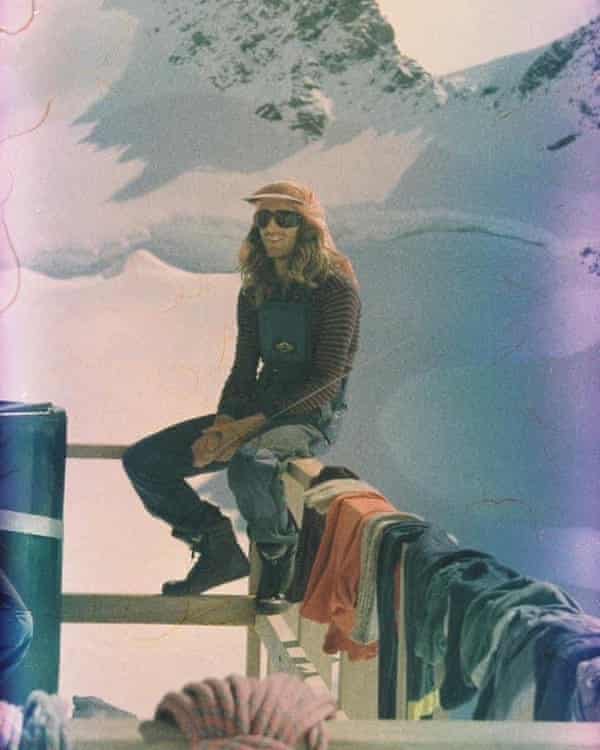

One of the men in the photos, with a big grin and long wavy hair, turned out to be 29-year-old Steve Robinson, the pictures taken in 1997 just before he was killed and buried by an avalanche.

Twenty-four years ago, Robinson and his friend Richard Stiles were having a breather on the side of the mountain when an enormous block of ice crashed into the snow and set off an avalanche. Stiles leaped out of the way and survived, but could see no sign of Robinson – or his backpack.

Until he saw those pictures on Facebook on Saturday night.

Now 53, Stiles is a doctor in the Australian town of Lithgow. It was “discombobulating”, he says. “In an unexpected way it brought me back to a part of my life that I thought I had settled away.”

Stiles and Robinson had “lots of pretty serious adventures” together, Stiles says, “but this was the one trip both my wife and my mother had a premonition about. My wife wanted me to bail on it.”

Not that he believes in premonitions, but he did later hear it was going to be warmer than expected and “they were predicting some instability”.

Stiles says Robinson has remained a “potent presence” in his life, as “a beautiful man, an amazing man, a kind man, a talented man, a man full of smiles”. He has been thinking about their story coming back to life, in a way.

“There’s something about a moment that was captured on film, and then buried for a quarter of a century, and then randomly come across, and then through careful attention and a bit of luck, the story was unravelled and again came to life,” he says.

He talks about the power of adventuring, of making life-and-death decisions in the moment, on a mountain, and concludes that he and Steve made the right decisions on that fateful climb.

“We did need to traverse right underneath a band of ice cliffs on our descent, but we were doing it during the safest part of the day, when the sun had not softened the ice,” he says.

“It was one of the more horrible feelings that I’ve had, to have to turn around and walk away from that avalanche, knowing that a dear friend was no longer with me, in fact buried underneath some massive ice boulders, that somehow I had escaped.

“The phone call, also, to tell his mother that he was no longer with us, was pretty awful. I remember the silence at the end of the phone.”

Robinson’s mother and sister both describe him as someone who was interested in human rights and the environment. A solar physicist, Robinson was working on developing photovoltaic cells before that fateful trip.

His mother, Marcia Robinson, is now 86, and living in Geelong. “I just sat in this chair and tried to comprehend it,” she says of the discovery. “He was a child that was fair, that was interested in human rights, who helped the underdog.

“He would step back and watch, before jumping in.”

His older sister Chris Schiesser says it has been a strange rollercoaster of emotion seeing the pictures from the past.

“Anything that comes to you once someone has passed … that comes to you from beyond the grave, it’s a bit of a gift,” she says. “It’s a wonderful new bit of them.

“At the same time I’m thinking, oh my god, that’ll have been taken the day before he died and he’d have had no idea. So it’s been hugely emotional but also wonderful.”

He was calm and measured, she says. A humanitarian with a strong moral compass.

“He lived a good clean life with a low [carbon’] footprint,” she says.

Robinson, then, would probably be unhappy with the way climate change is melting the New Zealand glaciers – a process that, terrifyingly, means more bodies are likely to be found.

“Mountains and glaciers don’t lie,” Stiles says. “Even in 25 years the snow is lessening on Mount Cook.

“I hope for the family’s sake that Steve doesn’t end up being found.

He says Robinson is now “quiet in the glacier in the ice beneath Aorangi”.

Schiesser feels the same way.

“We actually can’t think of a better resting place for him,” she says. “As far as we’re concerned we hope that’s where he’ll always stay. It’s the most magnificent place.”

In one of the photos, saved from a camera that survived an avalanche, Robinson sits on a deck railing, back to the mountain. Inside the hut, his mother says, is a table, and on that table is a chessboard that Steve engraved “so that people would have something to do”.

“I always thought of that as sort of a memorial to him,” she says.