‘I’ve never said we should plant a trillion trees’: what ecopreneur Thomas Crowther did next

The ecologist admits ‘messing up’ in the past, but says his Restor project will be ‘a Google Maps of biodiversity’, showing the impact of restoration – from a forest to your own back garden

Listen to our podcast: Can we really solve the climate crisis by planting trees? – part one

Last modified on Wed 1 Sep 2021 08.55 EDT

Thomas Crowther understands more than most the danger of simple, optimistic messages about combating the climate crisis. In July 2019, the British ecologist co-authored a study estimating that Earth had space for an extra trillion trees on land not used for agriculture or settlement. Its implications were intoxicatingly hopeful. By restoring forests in an area roughly the size of China, the press release accompanying the paper suggested two-thirds of all emissions from human activities still present in the atmosphere could be removed.

The study, led by Jean-Francois Bastin, a postdoctoral researcher at Crowther’s lab in ETH Zurich, Switzerland, was the second most featured climate paper in the media in 2019, according to one analysis. It inspired the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) One Trillion Trees Initiative, launched last year after Salesforce billionaire Marc Benioff read the paper on the recommendation of Al Gore, the former US vice-president. The Time magazine owner told everyone he could about the research: chief executives, friends and world leaders, even convincing climate sceptic Donald Trump to back the WEF initiative with a multibillion tree commitment.

But since the study was published, it has faced intense scientific criticism. Several ecologists were outraged that forest restoration was framed as the “most effective climate change solution to date”, arguing that it was a dangerously misleading distraction from the urgency of cutting fossil fuel emissions.

Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist and director at California’s Breakthrough Institute, pointed out problems with the paper when it came out. “Reforestation might buy us up to a decade of time – maybe six or seven years of current emissions,” he says. “It’s not nothing, but it doesn’t really fundamentally change the story: we still need some pretty massive reductions in our emissions.

“The brutal maths of climate change is that, as long as emissions are above zero, the world will continue to warm. You’re going to max out pretty soon if you only try to use forests. Tree planting is not an alternative to mitigation.”

Others thought the paper dramatically overstated where new forests could grow by including savannahs and grasslands in its artificial intelligence-derived estimate of land suitable.

There was also division over how to reforest: allow humans to plant enormous numbers of saplings or leave ecosystems to regenerate on their own? Some feared the paper would be used to justify indiscriminate tree-planting, with damaging consequences for biodiversity, agriculture and access to water.

The science behind the press release’s claim that new forests could suck in two-thirds of all historic human emissions remaining in the atmosphere was also questioned.

In May 2020, the study’s authors made three corrections, including an acknowledgment that they were incorrect to state “tree restoration is the most effective solution to climate change to date”, and clarifying that new forests could absorb about half as much carbon from the air as the paper initially appeared to suggest.

They had already issued a lengthy response to criticisms in the journal Science, explaining that they did not mean reforestation was a potential magic bullet or a substitute for reducing fossil fuel use. Reforestation was a potent tool for climate crisis mitigation, just less so than initially suggested, and certainly not a replacement for decarbonisation.

“We messed up the communications so badly,” Crowther says, clearly wounded by the backlash. He takes “full responsibility” for the failures, and, with a team of researchers, has been re-doing the analysis with a different approach.

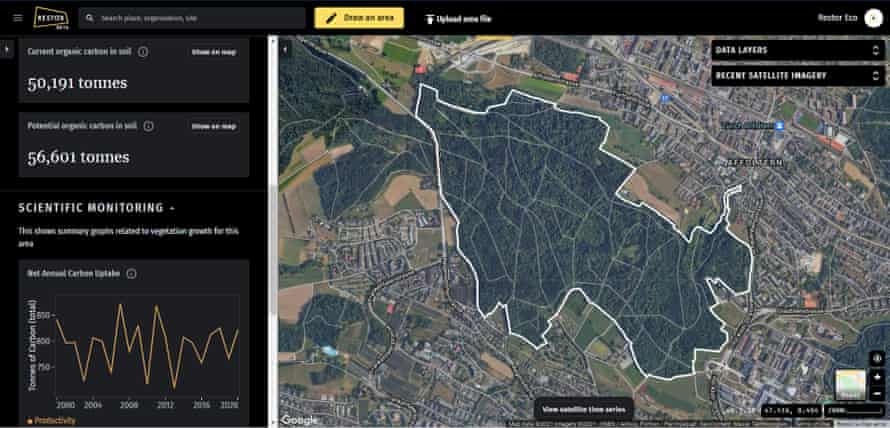

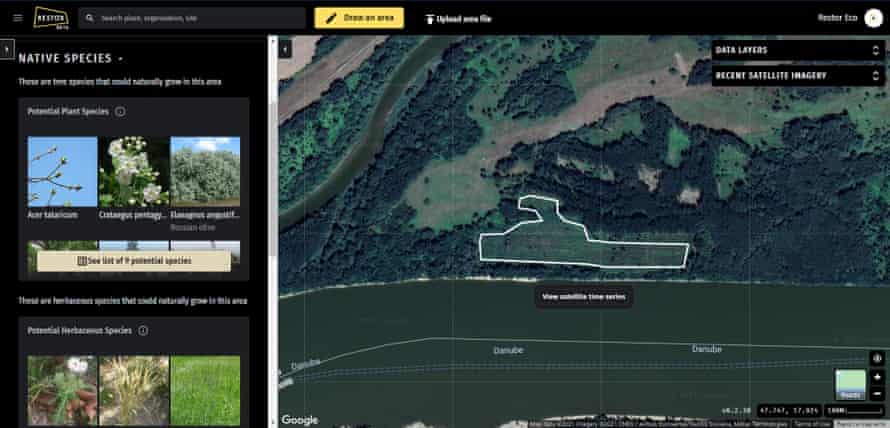

Earlier this year, he launched the platform Restor – his “life’s vision” – which brings together the latest data and thousands of conservation projects in a “Google Maps of biodiversity”. It is a project typical of his bigpicture thinking in ecology – partly a consequence of a near fatal stroke in his mid-20s – that has helped propel the 35-year-old from a postdoctoral researcher to a leading voice, with his own lab, in just a few years.

Benioff views Crowther as a Steve Jobs of ecology, “an ecopreneur” who is using bold research to shine a light on nature’s potential to mitigate climate change and biodiversity loss. But the subject of the forest restoration controversy is never far away.

“I hate that people keep asking me: where are you going to plant these trillion trees?” Crowther says. “I’ve never in my life said we should plant a trillion trees. It gives the impression of plantations everywhere. There is definitely room for a trillion trees to be restored within ecosystems. But the idea of planting individual trees isolates them from the microbes in the soil, the birds, the animals and the other plants that are necessary.”

Since the British scientist was awarded a multimillion pound long-term grant in 2018 to form the Crowther Lab, his multidisciplinary team has been trying to map the ecology of the planet. He caught the eye of his Dutch backers, DOB Ecology, following his 2015 paper counting the planet’s three trillion trees, which remains the most authoritative estimate to date.

At ETH Zurich, researchers employ machine-learning techniques and satellite imagery to gain understanding of the Earth’s soils, fungi, carbon cycle and forests. The findings have been published in leading journals, and Jane Goodall, David Attenborough and others cite Crowther’s lab research. These include counting the planet’s 0.4 sextillion nematodes, Earth’s most abundant animal.

Restor, developed in partnership with Google, will bring all of this research together. Combining the latest biodiversity metrics with a global map of restoration projects, he hopes Restor will allow anyone with an internet connection to assess the impact of the programmes and bring more accountability and direction to conservation.

The platform is focused on signing up NGOs initially – about 30,000 so far, with tens of thousands in the process of being uploaded. It is hoped that, in time, multinationals will list suppliers of raw materials, such as cocoa, cotton and wood.

Consumers would be able to interrogate the credentials of their cup of coffee, clothing or a corporate net zero claim simply by looking up a Restor page to see how an agroforestry project or reforestation scheme is managing the land. The public will also be able to assess the impact of their own back garden.

Crowther demonstrates this over Zoom by highlighting his mother’s garden in Cardiff and pointing out the native plant species she could introduce, and the garden’s carbon sequestration potential.

“Everyone with a smartphone will be able to show where their purchases came from,” says Crowther. “I love Ikea – one day I’d like to go round, and find that there’s an iPad with a Restor page, and it shows the spot in Iceland where the wood came from. Once there’s transparency across the whole system, everyone can call you out.

“Everyone [in restoration] wants to do good. Many do successfully achieve that. And many struggle because they don’t have the right information,” adds Crowther, who is to co-chair the UN’s Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. “There’ll be loads of plantations that corporates have set up. Restor will show very clearly those that are failing. But the reaction we need to give to those people is: you’re doing this totally wrong because you’re lacking ecological information. Make sure you get the right mix of species and the right social context and you can actually have a positive impact.”

Data on the outcomes of conservation projects, available to academics, will facilitate a better understanding of what does and does not work in restoration ecology, he hopes. Last month, a global review of tree-planting initiatives in the tropics and subtropics since 1961 found that while dozens of organisations reported planting a total of 1.4 billion trees, just 18% mentioned monitoring and only 5% measured survival rates.

Ecologists overwhelmingly agree forests have an important role to play in climate crisis mitigation – alongside peatlands, wetlands and other solutions – despite disagreement over the carbon accounting. Researchers can map where projects are taking place and help prevent duplication, says Crowther.

“It’s a little shocking, but we don’t actually have a good global perspective of where restoration is occurring,” says Dr Susan Cook-Patton, a scientist at the Nature Conservancy and a member of Restor’s scientific advisory panel.

“Once we know that, then we can start targeting our questions: are those places recovering trees faster than places where there’s not a restoration project? We can find the places that seem to be doing really great and learn from them. We can find the places that are not doing well, or as well as expected, and learn from them, too.”

If successful, the platform could help move away from the “carbon in, carbon out” logic underlying many conservation projects. Restoring the world’s forests, wetlands and natural landscapes is an end in itself, Crowther is keen to emphasise, and carbon sequestration is not the primary focus.

“The vision is to try to bring integrity into the process of protecting biodiversity,” he says.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features