Meet the Batistas: the global beef barons battling for control of Australia’s meat

JBS, which is trying to take over pork producer Rivalea, now finds itself in a stoush with Andrew ‘Twiggy’ Forrest over Tasmanian salmon farmer Huon

In the end, it wasn’t the bribery of Brazilian government officials that put the Batista brothers, who own Australia’s biggest meat processor, in jail.

The authorities never actually brought the brothers, Wesley and Joesley, to trial over allegations they engaged in the large-scale corruption of the country’s politicians. Instead they agreed a plea deal with them.

Instead what led to the Batistas, the country’s most powerful businessmen, spending several months in 2018 behind bars while awaiting trial were allegations of insider trading – using the privileged information of that very plea deal for their own financial benefit.

These days the brothers are back in full control of their global meat empire, JBS. And they have big plans for Australia.

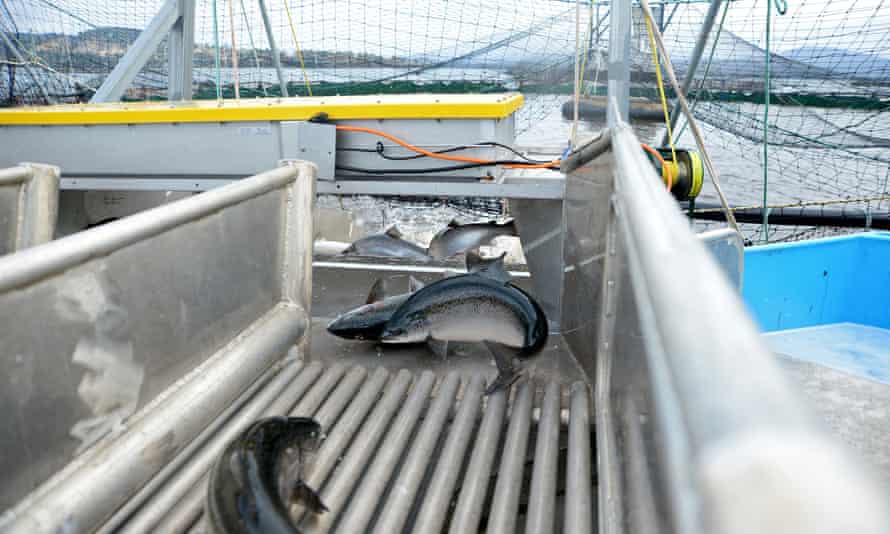

Their company is in the middle of taking over Australia’s biggest pork producer, Rivalea, and in the past fortnight has become embroiled in a public stoush with the mining billionaire Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest over control of Tasmanian salmon farmer Huon.

These deals are huge, worth a total of close to $700m, and have also ignited a fierce debate over who should control much of the meat Australians eat every year.

JBS Australia is a subsidiary of JBS in Brazil, where the brothers are the founders and biggest shareholders. It already controls about a quarter of Australia’s meat market, including the country’s biggest ham and smallgoods manufacturer, Primo, while Huon is the nation’s second-biggest salmon farmer.

Competition watchdog the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission is investigating the Rivalea takeover, with an eye on whether allowing JBS to add more pork to its existing operation, which currently concentrates on lamb and beef, would stifle competition.

Forrest has used full-page newspaper ads to call on JBS to treat animals better in the slaughterhouse while at the same time attacking the Batista brothers over JBS’s corruption record in Brazil through the press.

Environmentalists are also unhappy with the takeover, calling on treasury’s Foreign Investment Review Board to block it.

“During its rapid rise to become the world’s biggest meat packer, JBS and its network of subsidiaries have been linked to allegations of high-level corruption – including the biggest fine in corporate history, $3.2bn, after bribing hundreds of politicians – modern-day slave labour practices; illegal deforestation, particularly in the Amazon; animal welfare violations; major hygiene breaches and price fixing, including fines,” the Tasmanian Greens senator Peter Whish-Wilson told parliament earlier this month.

“I warn JBS that they won’t be expanding in Tasmanian waterways without a fight, a significant community fight.”

Takeover fights are not the only battles JBS is fighting in Australia. It is also embroiled in litigation with the Australian Taxation Office over the use of legal privilege to avoid disclosing documents.

Meanwhile, there remain questions about the bona fides of the conglomerate’s entry into Australia in the first place.

JBS came to Australia in 2007, indirectly, by buying US group Swift, which already had operations here.

The US$1.4bn purchase was partly funded by a US$362m loan from Brazil’s National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES).

This loan was part of a “sequence of reckless and/or fraudulent acts” that demonstrated “a fraudulent management of the public institution with the sole purpose of giving privileged treatment” to J&F Participacoes, the Brazilian company through which the Batistas control JBS, Brazilian prosecutors said in their criminal complaint against Joesley Batista. The allegations never went to trial.

It is not suggested that JBS Australia is implicated in any wrongdoing.

Quick GuideHow to get the latest news from Guardian AustraliaShow

Email: sign up for our daily morning briefing newsletter

App: download the free app and never miss the biggest stories, or get our weekend edition for a curated selection of the week’s best stories

Social: follow us on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or TikTok

Podcast: listen to our daily episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or search “Full Story” in your favourite app

To settle separate bribery charges brought by Brazilian prosecutors, in 2017 J&F agreed to pay US$3.2bn. Brazil gave the company generous terms – it got 25 years to pay.

The Batista brothers, meanwhile, entered into a plea deal that saw them avoid prosecution in a deal that included Joesley agreeing to spill the beans on his corrupt dealings and secretly record a meeting with the then president, Michel Temer – an event dubbed “Joesley Day”.

Having avoided that prosecution, Brazilian authorities claimed the brothers set out to financially benefit from the plea deal. They are said to have sold US$87.5m worth of JBS stock before it was announced, avoiding the fallout from a 30% fall in the company’s share price when the deal with prosecutors was made public.

The plea deal was revoked and each brother spent about six months in jail before being released into house arrest – Wesley in February 2018 and Joesley in March 2018. The case remains unresolved.

As a result of the brothers admitting to bribery, in 2019 the New Zealand Overseas Investment Office re-examined JBS Australia’s purchase in 2015 of Kiwi company Scott Technology, which makes factory machines.

The deal had been approved on conditions including that Joesley and Wesley remain of good character.

It concluded that the bribery they had admitted to meant they no longer met the bar, and obtained assurances JBS Australia was not in their control. Anna Wilson-Farrell, the head of regulatory practice and delivery at Toitu Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand, said the settlement with JBS was still current.

“We would consider taking action if the settlement agreement conditions were breached,” she said.

Legal stoush with ATO

JBS’s sprawling company structure, which involves subsidiaries everywhere from Australia to Russia, Hong Kong and Kuwait, has also drawn close attention from banks and the Australian Taxation Office.

JBS’s bankers, Deutsche Bank, has repeatedly filed suspicious transaction reports related to the movement of hundreds of millions of dollars around the empire with the US equivalent of Austrac, Fincen. Fincen requires financial institutions to file suspicious activity reports in a range of circumstances and the filing of a report does not necessarily mean anything improper has occurred.

Reports, obtained by BuzzFeed News and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, show Deutsche Bank reported a flurry of transactions in late 2015, saying it was making the reports as a consequence of the ongoing investigations into the company in Brazil.

Back in Australia, the ATO also has JBS under a lens.

It has launched legal action in the federal court seeking access to a large number of documents JBS and its adviser, big accounting firm PwC, refused to hand over during an audit.

JBS claims the documents are subject to legal professional privilege, which protects advice from lawyers being used as evidence.

Little information is publicly available about the legal stoush, which is due to go to trial next month.

However, the ATO has told the court LPP does not apply because “non-legal practitioners” were involved in creating the documents and because they were “not provided pursuant to a relationship of lawyer and client sufficient to ground a claim for legal professional privilege”.

JBS also told the court the ATO’s legal action should be put on hold because it feared being prosecuted for failing to hand over the documents during the audit.

However, the ATO told the court it had no intention of doing so and was prepared to provide an undertaking not to.

The ATO has been targeting what it says are invalid claims of LPP by big accounting firms for about two years – in December 2019, Guardian Australia reported that second commissioner Jeremy Hirschhorn had travelled to the offices of accounting firms, including PwC, warning them that it would closely scrutinise privilege claims.

The battle for Huon

The ACCC is expected to decide next month whether or not to oppose JBS’s takeover of Rivalea.

But the company hasn’t waited before pushing ahead with its attempt to buy Huon.

It is offering $3.85 a share, 60% more than stock was fetching on the ASX in February, when Huon decided to put itself up for sale.

The offer, which values Huon at more than $420m, is endorsed by the salmon farmer’s board but Forrest has accumulated a blocking stake of 18.5%.

If it can defeat Forrest, JBS will then have to deal with Firb, which has shown itself more ready to knock back deals in the past 18 months, although it seems largely concerned with Chinese state influence.

In the battle for Huon, Forrest questioned whether JBS adhered to the concept of “no pain no fear” for animals in the slaughterhouse.

JBS rejects the criticism.

“JBS unequivocally supports the concept of no pain, no fear and upholds the highest standards of animal welfare in this country,” Brent Eastwood, the chief executive of JBS Australia, said in a statement.

“JBS has zero-tolerance for animal abuse from our own employees and third parties in our transport supply-chain, processing plants or feedlots.”

He said the company would “apply its uncompromising commitment to animal welfare and sustainability” to build on the legacy of Huon’s founders, the Bender family.

Guardian Australia also put detailed questions about the behaviour of the Batista brothers, its tax affairs and its international transactions to a JBS representative. They did not respond.