‘I don’t believe anyone is safe’: drought rules spark accusations of racism in California outpost

Siskiyou county says water restrictions are aimed at pot growers. Hmong American residents say they’re being targeted

“I love the smell of diesel power in the afternoon. It smells like victory.”

The line, a play on the quote from the Vietnam war movie Apocalypse Now, is the first uttered in a July video by Doug LaMalfa, the US congressman for Siskiyou county. In the background, bulldozers are destroying what appears to be a field with marijuana plants.

LaMalfa’s video was a response to a call from the Siskiyou county sheriff, who had invited citizens in this remote region in northern California to help his department in the fight against illegal marijuana grows.

The sheriff’s request, and the congressman’s video, were the latest in an intense standoff between Siskiyou officials and Hmong American residents of the county.

Tensions in Siskiyou had been rising for years, but they have escalated this spring and summer amid the historic drought that has ravaged the American west.

This year, county officials announced several ordinances they said were intended to stop illegal, large-scale marijuana operations from depleting the county’s ever shrinking water resources.

The county banned people from transporting large amounts of water on certain county roads and the sheriff warned local businesses not to provide services or supplies, including soil, to “known illegal commercial cannabis sites”.

But the measures mainly targeted one neighborhood in the county: the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision, a 1,600-plot community where more than 1,000 Hmong Americans live.

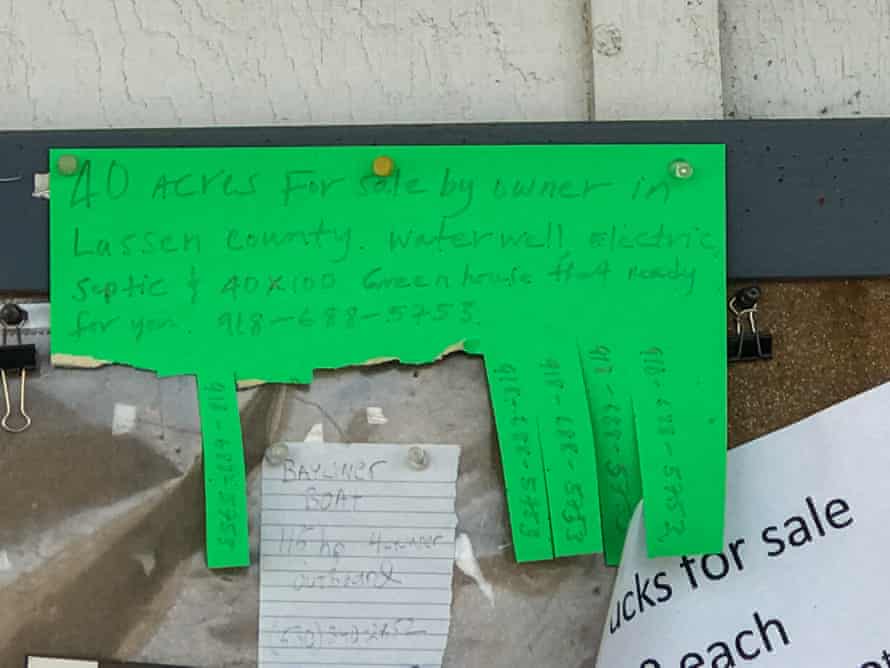

The sprawling residential area, which has dirt roads that connect mostly trailers or sheds, lacks basic infrastructure such as wells or a centralized sanitation system. The roads around it were included in the water transport ban, and without water being trucked in, residents said, life became eminently difficult.

“Without the water to feed my animals, they’re dying as the day goes on,” said Cheng Xiong, a 54-year-old Hmong American living in the subdivision.

The sheriff and other county officials have defended the measures as an effective tool in a time of historic water shortages, alleging that the subdivision is rife with marijuana cultivation sites that dry up the land.

Subdivision residents say the restrictions are about more than water. They allege officials are targeting an entire community in their battle against pot growers, a policy, they say, that comes after years of discrimination against the ethnic minority.

“The sheriff don’t care about us. They just want to force us out of here. Even though we’re residents in this county, they still don’t care,” Cheng Xiong said.

‘You give us a piece of garbage land, we’re gonna thrive’

Sitting in the shadow of the mountain it is named after, the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision looks rugged and parched. Just up the highway, the landscape is lush and green, with hay neatly stacked and a “farmers for Trump” sign hanging on the side of a barn. But around the subdivision’s windy roads dust blows, coating its trailers, burned sheds and dried trees. Hmong Americans started moving to this rural outpost in 2015.

There are more than 300,000 Hmong Americans living in the US today. The US recruited the Hmong to fight in Laos during the Vietnam war, arming tens of thousands against the North Vietnamese army. In 1975, tens of thousands of Hmong refugees arrived in the US, and today most live in California, Minnesota, Wisconsin and North Carolina.

Many Hmong Americans in Siskiyou in 2015 bought inexpensive, undeveloped plots in the subdivision. They started growing crops on the volcanic rock-covered land, including marijuana, said Tou Ger Xiong, a Minnesota-based activist who has been working in the county.

“We’re farmers, we’re good at that,” Tou Ger Xiong said. “You give us a piece of garbage land, we’re gonna thrive. We’re gonna make stuff grow.”

Tong Xiong, an army veteran who served in Iraq, came to the area nearly four years ago, enamored with the landscape and country living. “The first time I was out here in the mountains, it felt like I was free,” he recalled.

But Siskiyou was not exactly a welcoming place, Tong Xiong admitted. Stores sometimes refused to sell Hmong American residents basic goods. Landlords declined to rent them homes. Neighbors have flipped them off as they walked by.

Hmong Americans came to make up at least 4,000 of 43,000 people in Siskiyou county, which remains largely white. Tensions increased as marijuana cultivation expanded.

War over water

Marijuana is legal in California, but Siskiyou forbids commercial grows and outdoor growing. County officials blamed Hmong Americans for a rising number of illegal growing operations. In 2015, the sheriff’s office estimated there were about 250 marijuana grows in the county. By 2017, Jon Lopey, the then county sheriff, told the Sacramento Bee there were as many as 2,000 illegal grows on private property. “Too bad they didn’t use their ingenuity, intelligence and skills to engage in something lawful,” he said of Hmong American residents.

In 2020, as Siskiyou entered an extreme drought, county officials prohibited the use of groundwater for marijuana cultivation and banned well owners from selling water to marijuana growers. The county then sued a local landowner for letting residents use his private well – which they’d done for years, they say.

In May 2021, county supervisors also started requiring permits to extract groundwater for off-site use, and barred the transportation of more than 100 gallons of water on certain county roads, including in the area around Shasta Vista. Meanwhile, the sheriff’s office warned local businesses not to provide services or supplies, including soil, to “known illegal commercial cannabis sites”.

In July, LaMalfa put out his video, quoting the Vietnam war movie before bulldozing land on a subdivision largely populated by people whose families fought alongside the US in south-east Asia.

The ordinances were necessary, said the county’s sheriff, Jeremiah LaRue, due to both water issues and environmental degradation from pollution such as chemical leaks and buried trash. “It’s essentially like a third world country when you go out there so we have a serious concern with the environmental health and general living conditions.”

Crime had also been an issue, he added, with three homicides in the subdivision since 2020.

The restrictions had some support in other parts of the county. Many older county residents, some concerned about their own water supply, stood behind the measures and the sheriff’s department, said Steven Izzard, the weekend manager at a local supply store.

Concerned residents cited fears about the environment, and a county takeover by “crime syndicates”. “The good work of Sheriff [Jeremiah] LaRue enforcing the water limitations into the grow areas has been effective in reducing some of the criminal operations,” wrote Liz Bowen, a local newspaper columnist.

But the impacts in the subdivision were dramatic. Without trucks bringing in water, subdivision residents struggled to get enough water to cover basic needs, residents said.

Two people told the Guardian that they were forced to buy water for their families in secret from stores still willing to help them. One resident told a California court he and his wife were constantly thirsty and could only bathe once a week, leaving him deeply depressed.

Officers have become a frequent presence near the subdivision, residents said. “They’ll pull you over for no apparent reason and then follow you back for no reason,” said Tong Xiong, who has become a community organizer in recent months. “They’re profiling you. They followed one of my grandmas all the way back home.”

Bee Xiong, a relative of Tong Xiong, said he had been stopped by police six times this year, which he attributes to his advocacy. Police have searched his land for signs of marijuana grows and routinely parked outside the property, Bee Xiong said.

Bee Xiong, whose father fought alongside US troops during the Vietnam war, was baffled by the situation, Tong Xiong said. “He has always been around American people, so he doesn’t understand all the hatred toward Asians,” he said.

‘It’s Jim Crow racism’

Subdivision residents acknowledge illegal marijuana grows are operating in the area, but there’s marijuana cultivation all around the county, they point out.

Lawyers for Hmong American residents in the area, citing data they attribute to the sheriff’s office, say just 3% of the county’s estimated 2,500 illegal marijuana grows are located in the subdivision. But LaRue says that number is inaccurate and the actual number of grows in the community is closer to 1,700, with some single properties hosting multiple growing operations. Legal outdoor marijuana crops use about the same amount of water as tomatoes, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.

Residents also dispute that the neighborhood is merely one of pot growers. “They’ll paint everybody out here as [marijuana growers]. But at this point it’s no longer about growing pot. This community is not the only community that grows pot,” said Tong Xiong.

Meanwhile, subdivision residents say, vitriol against Hmong American community members has increased. In social media posts shared with the Guardian, people talk about burning the Shasta Vista subdivision down to help their “community that’s being taken over”. During a recent wildfire, someone put up signs pointing at the subdivision that read “North Korea“.

In June, weeks after Siskiyou county passed the water truck ordinance, local residents filed a lawsuit against the sheriff and board of supervisors. Civil rights organizations including the ACLU and Asian Law Caucus have filed a brief with the court alleging that county officials have violated Hmong American residents’ constitutional rights.

“This is old-fashioned racism. It’s Jim Crow racism,” Angela Chan of the Asian Law Caucus said. The county has “clearly targeted Hmong residents to make life extremely difficult”, she said.

“This case is really about equal protection under the law,” said John Do of the ACLU. “This is a fairly blatant example of targeting a community based on their race and ethnicity.”

Mai Vang, a Sacramento city councilmember who has been working with local activists, believes Siskiyou county is using its water policy to justify discrimination.

“There are disproportionate rates of cannabis enforcement on Black, brown and south-east Asian communities. What you’re seeing is local law enforcement are criminalizing communities to justify the implementation of policies.”

LaRue, the county sheriff, said the ordinances were about targeting crime, not any group of people.

“We don’t target any people. We target crime. It’s unfortunate that is sort of the card that’s being played,” he said.

“[The water ordinance] was a reaction to the huge amount of illegal grows that are occurring out in the Shasta Vista subdivision,” Ed Valenzuela, the vice-chair of the Siskiyou county board of supervisors, told the Guardian. “There is a misconception that there are all these people living out there. They’re not – they’re just growing marijuana. If they were growing carrots or tomatoes we wouldn’t be having this discussion.”

“Come up and see for yourself,” Valenzuela added. “I’ve been out there and I’ve looked at it and I’m appalled at what they’re doing to the land. They’re breaking the law.”

Congressman Doug LaMalfa did not respond to a request for comment.

A police shooting in Siskiyou

Tensions between Hmong American residents and the authorities came to a head on 28 June, when the lighting-sparked Lava fire threatened the neighborhood.

Many subdivision residents defied mandatory evacuation orders, afraid that the county wouldn’t fight to save it from the flames.

Bee Xiong, too, at first refused to leave his home.

“You need to leave the area. I’m not playing games any more. We’re not doing this. You leave your property,” an officer can be heard telling him in a video shared with the Guardian. “And if I arrest you then I’ll have to arrest your wife and then your kids go to child protective services.”

That evening, four police officers shot a subdivision resident, Soobleej Kaub Hawj. Hawj, 35, was killed inside his truck, at the intersection of the subdivision and the highway. His wife and children were following in the car behind his.

The law enforcement agents – officers with the Siskiyou county sheriff’s office, the California department of fish and wildlife and the Etna police department – later said that Hawj had ignored their directions, tried to drive around a roadblock and had pointed his gun.

Many subdivision residents have seized on the lack of information about the circumstances of shooting, and the whereabouts of Hawj’s dog in the month after the incident, as a sign that local officials won’t get to the bottom of what happened.

“We need to know Silk is alive,” Tong Xiong said. “We want the truth about her and the shooting.”

Residents have held protests to draw attention to the case, and one man went on a three-week hunger strike that alerted Vang and eventually the Asian Law Caucus.

Continuing tensions

Since then, a judge has ordered the county to enter mandatory mediation with the residents involved with the lawsuit in order to “ensure people living in the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision have water to meet their basic needs while the court considers the pending motion for a preliminary injunction”.

The sheriff said he would like to see Hmong American residents root out crime in the community. “We wouldn’t have to have this tense situation if there weren’t laws being violated,” he said. “They claim they want to be in this community and be part of it and I wish they would demonstrate that in how they’re taking care of the land and respecting the laws.”

Silk, LaRue said, was treated for an injury and has since been returned to Hawj’s family.

In the meantime, residents of the subdivision still struggle to get enough water. Tensions remain high and some Hmong Americans in the county feel under constant threat.

“With all the promotion of hate, I don’t believe anyone is safe,” Tong Xiong said.

But residents say Siskiyou county is their home, and they’re determined to stay. On a recent tour of the Shasta Vista subdivision, Tong Xiong reflected on why he came to the area, and how his children have grown to love living in the countryside. He is hopeful the county can change, he said while looking over the charred landscape, and committed to seeing it through.