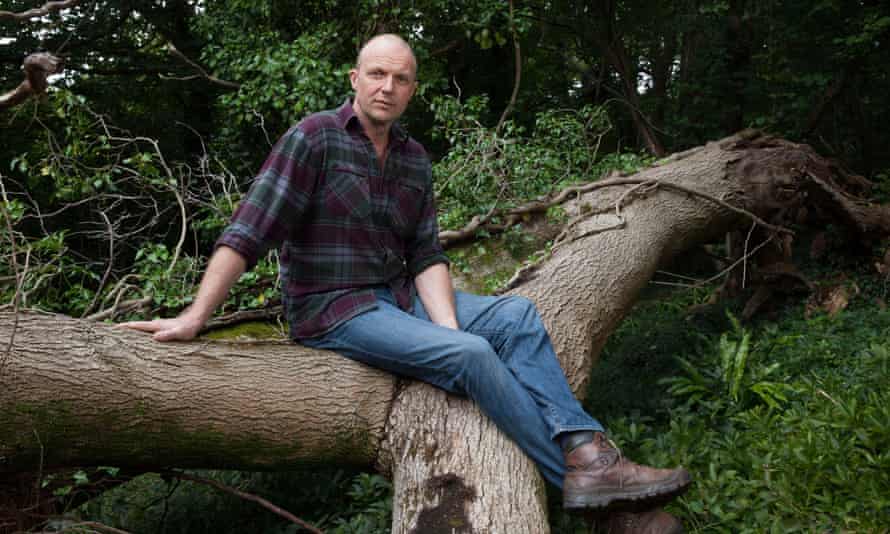

Paradise regained in the New Forest: no planes, no people. Just one man and nature

A cameraman who recorded the lives of a goshawk family in the New Forest during lockdown saw them as a symbol of hope

There were moments last spring when wildlife cameraman James Aldred felt guilty about how lucky he was. Commissioned before the pandemic to document the lives of a family of goshawks living in the New Forest, Hampshire, he was given special permission to carry on filming while the rest of the country locked down.

“If there is an Elysium, or an afterlife, I would like to think it’s the middle of the New Forest during lockdown,” he says. “It was stunningly beautiful.”

High in the trees, he kept a diary about his experiences, which he has now turned into a book. “It’s the story of how one family of goshawks living in a timeless corner of England shone like fire through one of our darkest times – and how, for me, they became a symbol of hope for the future,” he writes in the opening pages of Goshawk Summer: A New Forest Season Unlike Any Other.

As an Emmy award-winning documentary-maker who specialises in filming at height, using ropes to access forest canopies, he has spent years in the Amazon, Borneo and Congo, shooting the wildlife of the world’s most breathtaking jungles. But the New Forest in lockdown was like nothing he had experienced before.

“It was magical,” he says. “I can’t imagine ever getting to experience anything like that again. It was like going back in time 1,000 years.”

He grew up near the New Forest and has always known it as a place that is under several flight paths. But during lockdown, there was no sound pollution at all: “No flights, no cars, nothing.” The immediate benefit, he noticed straight away, was that the birds could communicate a lot better. “The air was filled with a lot of birdsong that was very far-reaching.”

Very soon after humans deserted the forest last spring, wild animals started reclaiming it, he says. One of his favourite memories is of a boar badger running down the middle of a one-way road “as if he was on his morning commute”. Another time, on an empty A36, Aldred suddenly came face to face with a muntjac deer. “In a landscape as ancient as the New Forest, that’s to be expected. There are badger setts which have been in the same place for centuries and deer that have been following the same game trails for generations. If we slap a road in the middle of the forest, it makes no difference to them, which is why we get so many road casualties in mating season.” Another time, he spotted 10-day-old rural fox cubs playing on the tarmac of the normally busy A35. “That was a real bittersweet moment, because those fox cubs had been born in lockdown. They had no experience of human beings at all. Or cars. As far as they were concerned, the tarmac was an open place to play, where they could see danger coming. They felt safe there.” Soon, he knew, the 70mph traffic would be back.

Acutely aware that he alone had been given this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to observe how the wildlife behaved in the forest without humans around, for a documentary that will be out later this year, he began to develop “a sort of imposter syndrome” about being there. “The sheer emptiness of the place… It felt weird, being out there in that paradise on my own. I felt overprivileged.”

Because of the location of the goshawks’ nest, he would spend up to 15 hours a day filming from a tiny platform that was strapped to a nearby Douglas fir 15 metres (50 feet) off the ground. Most of the time, he hid in a small “Doctor Who-style Tardis” – a camouflaged canvas tent that was about four-and-a-half metres high by one metre square. “Working at height with cameras is a claustrophobic thing to do. You’re in self-imposed isolation.”

The tree was quite thin, and had an unnerving tendency to sway in the wind. “It was a bit like being below deck on a boat. I’d crouch there in the dark, with a camera, a tripod and everything I need for the day, losing feeling in my legs. And a lot of what I’d do would be just listening, trying to tune in to what the woodlands were telling me.”

He got to know which birds frequented each tree and what their alarm calls were. “You can work out what they are telling other birds in the wood. And if you can break that code, then they can actually inform you when there’s a predator around.”

Even though goshawks have an unsettling ability to silently come and go, the alarm calls of these other birds would warn him when they were on their way. “By listening to what the birds in the forest were saying, I could work out which direction the goshawk would be coming from and be ready with the camera.”

For goshawks, who feed on songbirds, it was a spring like no other. “The lack of disturbance meant that songbirds had a good season – and if they have a good season, then the goshawks do, too.” But for the forest’s endangered ground-nesting birds, such as curlews and lapwings, it was a very different story.

“When lockdown restrictions eased, it went from one extreme to the other in the forest.” Greater numbers of people than usual converged upon the national park and there was a sudden, exponential backlash of disturbance levels – just as the chicks of these birds were hatching.The popularity of “pandemic puppies” soared and out-of-control dogs also became a big problem in the forest. “I saw so many incidents of mobbing behaviour of ground-nesting birds by dogs. For the birds, it was life and death, because they have invested everything in their nest, but for the dog it was just a game of chase. Often, the owners didn’t really understand what was going on.”

But he says the Forestry Commission learned valuable lessons about how to manage visitor numbers and woodland paths. “The absolute mania that occurred in the immediate aftermath of lockdown gave keepers a glimpse of what the pressures on the forest are going to be like in 20 years’ time. It’s given them a heads-up, an opportunity to prepare for that.”

-

Goshawk Summer: A New Forest Season Unlike Any Other by James Aldred is published by Elliott & Thompson (GBP14.99). In memory of Aldred’s father, who died last year from pancreatic cancer, a portion of the royalties from sales of the book will be donated to Marie Curie.