What really counts? How the patriarchy of economics finally tore me apart

After 10 years of writing about capitalism I saw that the erasure of women is not only palpable, it’s bound to my own flesh and blood

… is the economics profession a functionary and tool of patriarchy – or is patriarchy a functionary and tool of economics? – Marilyn Waring

Economically, the rupture of 2020 showed us two things: that our lives depend on care work, especially the unpaid care work still mostly done by women; and that another way is possible.

It’s timely that Covid-19 has brought women’s traditional realm, the household, into clear and blinding view – because economics, the intellectual discipline that most shapes policy and funding decisions around the world, has its root in the ancient Greek word for household management. And if any discipline is in need of an influx of expert household managers to transform its ossified thinking and reimagine it for this new millennium, it’s economics.

In its current state, mainstream economics is failing to address the many critical issues of our times, including gendered and racial violence, climate change, inequality, poverty, hunger, species extinction, ecosystem destruction, land theft and the privatisation of water. As Ross Gittins, economics editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, wrote in 2020: “leading thinkers among the world’s economists are still grappling with the embarrassing question of why their profession’s advice over many decades seems to have made our lives worse rather than better.”

As the past year has demonstrated, women excel in household management. Yet it was thanks to a series of deliberate decisions made during the 19th century that women’s critical labours were designated “unproductive” and simply wiped from view. Key to these erasures was Alfred Marshall, the revered father of neoclassical economics, who advocated strict limits on women’s choices lest they behave selfishly. Women’s reproductive labour had already been excluded from the realm of economics by Adam Smith and others, but Marshall mapped this onto a new distinction between market and non-market work.

It was bad enough that the 1881 census of England and Wales had explicitly placed wives and other women engaged in domestic duties in the “Unoccupied Class”; but subsequently, following Marshall’s advice, the “Unoccupied Class” was struck from the census categories altogether. Why? Because if this main female occupation had been included in the reckoning, “the proportion of occupied women would resemble that of men”. In his influential work Principles of Economics, published in 1890, Marshall wrote that employing women was “a great gain in so far as it tends to develop their faculties; but an injury in so far as it tempts them to neglect their duty of building up a true home, and of investing their efforts in the personal capital of their children’s characters and abilities”.

Does this sound outdated? Marshall’s view continues to inform the mathematics of the global economy, the census reports and national income accounts that generate the allegedly objective numbers that global policymakers depend upon.

This erasure was institutionalised in the United Nations System of National Accounts (UNSNA) in 1953, an accounting system that had come into its own in the 1940s to allow the US and Great Britain to manage their wartime economies. Governments now use the UNSNA to generate annual gross domestic product (GDP) figures, which have become the default measure of economic growth. By their calculus, the following expenditures all boost GDP and so, by definition, boost economic growth: the costs of war (currently estimated at US$14 trillion a year globally), illegal people and drug trafficking, and cleaning up pollution such as oil spills.

But women’s unpaid domestic labour and all unpaid caring work are not counted and so don’t contribute to GDP or economic growth. Yet in 1995 the UN Human Development Report estimated the value of women’s unpaid work at US$11 trillion per annum. It suggested that if women’s work was properly valued, it’s possible women would emerge in most societies as equal if not the major breadwinners, given they put in longer work hours than men. If national statistics fully recorded women’s “invisible” economic contribution, the report stated, it would be impossible for policymakers to ignore them in their policy and funding decisions.

If only our work were counted – then we couldn’t be ignored! We are half the world’s population: the numbers are on our side. So what if we demanded, in this new Covid-inflected world, that every government redirect that US$14 trillion currently spent each year on war and death-mongering into our life-giving and nurturing work?

Brilliant women at a wrong moment in history

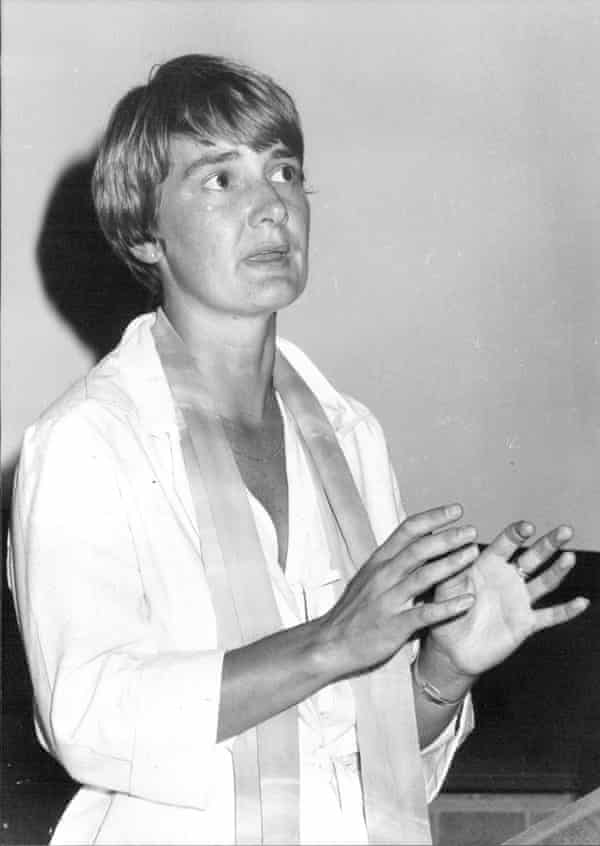

If the economic erasure of women is palpable, it’s bound to my own flesh and blood. In 2018, after ten years of writing about capitalism, I began to think specifically about women and economics. It’s a recurrent theme in my family: my grandmother, as a runaway teen, worked as a clerk at the Bank of England during the first world war; two of her daughters graduated in economics during the second. I studied economics in the late 1980s and now my daughter is studying economics.

When my grandmother died she left me her scrapbook. The tale I read there in newspaper cuttings is one of four dazzling children: three girls and a boy, my father. But there’s a darker story behind its fragments, a story of women and economics. My father’s lifelong illustrious career stands out, first in economics journalism, then in finance and banking – and behind it sit the thwarted careers of my aunts, brilliant women at a wrong moment in history. The early promise of the youngest, Nancy, is told in a flurry of press clippings.

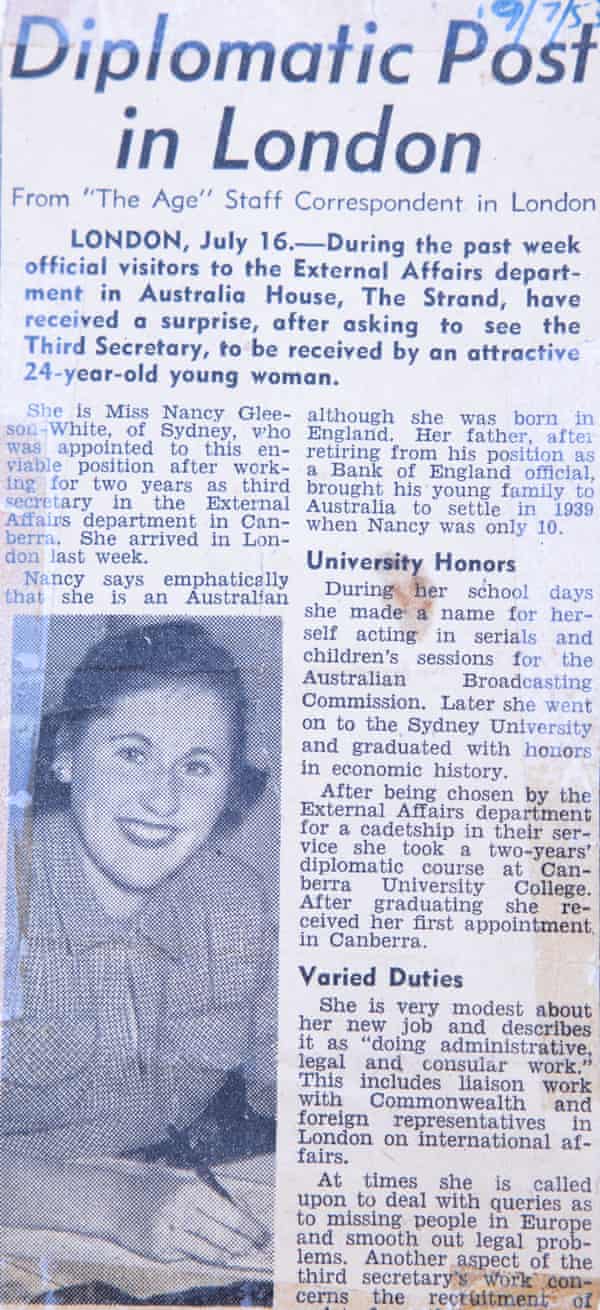

When Nancy first appears aged 12, she’s already a radio veteran: “In the two years she has been in Sydney since coming from England, Nancy Gleeson-White … has made 150 appearances on the radio.” Soon after, there’s this:

Trained for the stage, Sydney actress Nancy Gleeson-White has won high economics honours at Sydney University, being the only woman in the history of the economics school to graduate with first-class honours. Now a cadet with Department of External Affairs … she hopes her career will take her abroad. Aged 20, she was one of three women from all over Australia to fill cadetship vacancies.

In 1953, aged 24, she became the first Australian woman diplomat to be appointed to Great Britain. As I understand her life, this was the moment of her undoing. In London she fell in love with a leading British diplomat and, in order to marry him, she had to give up her own career. That was the rule of the day. From then on in my grandmother’s scrapbook, Nancy is Lady Tomlinson, the charming wife and society hostess of a star British ambassador. She fades from view, first engulfed by articles about her husband, then vanishing completely.

In 1974, after breaking down, Nancy was given one of the last leucotomies in England – or lobotomies, as they’re called in America.

Five decades on, the female erasures my aunt so horrendously and literally embodied still infect and misdirect the mechanisms that govern the global economy.

In 1993, the UNSNA did introduce “satellite accounts”, which give guidance on valuing unpaid household work by calculating either its inputs (what the unpaid labour would cost if paid for) or its outputs (the value of the goods and services produced). But this labour is still defined as being outside the UNSNA production boundary, so it’s still excluded from “The Economy” and therefore from the official statistics that run it. In Australia in 2006, the last time this work was measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), unpaid household work would have increased the GDP by 39.2%. While the ABS parroted that measuring the value of this work was “a worthwhile pursuit” because it gives “a more complete picture of the nation’s economic activities”, it nevertheless continues to churn out incomplete pictures of Australia’s economic activities: annual GDP figures that give unpaid household and other care work the exact value of zero.

This, along with the erasure of the rest of the living systems of the planet, is literally killing us. Economics is historically blind to women and households, and to the natural world.

Still undervalued and underpaid

The subject of women and economics is vast and ancient – but as a scholarly enquiry, it’s relatively recent, dating to the landmark 1988 book Counting for Nothing: What Men Value and What Women Are Worth, by Marilyn Waring, former New Zealand politician and founder of feminist economics. Waring has said of her research into the UNSNA: “As a feminist in the 1970s, discipline by discipline, we were uncovering the ways in which male experience spoke for all. I suspected economics would be the same, and yes it was.” When she finally read the UNSNA’s many volumes, what she found made her weep: a passage that “casually dismissed all the unpaid labour traditionally done by women as ‘of little or no importance'”. This value judgement was used to justify its exclusion.

If this begins to suggest the systemic magnitude of the problem, here are three more facts that bring it home. First, in Australia in 2020, women were paid an average of $242.90 per week less than men – women are still undervalued and underpaid, and our work is generally more precarious than men’s.

Second, one in every 130 women and girls on the planet – 29 million people – lives in modern slavery, a term that includes forced labour, forced marriage, debt bondage, domestic servitude and human trafficking.

And finally, men own over 80% of arable land on Earth. This shocking statistic was calculated by Oxford economist Linda Scott, author of The Double X Economy: The Epic Potential of Empowering Women. By cornering humanity’s main source of material wealth, men have been able to retain power over the world’s capital for hundreds, even thousands, of years.

Given this, it’s not surprising to learn that economics is still the most male-dominated discipline in universities across the globe – even more so than science, technology, engineering and mathematics. It’s time to change this. Reproductive rights, freedom to leave abusive relationships and other freedoms are nothing without economic empowerment. This is about more than improving individual conditions; this requires wholesale systemic change, the sort envisioned by writer and feminist activist Rickey Gard Diamond and her colleagues in 2020 when they founded An Economy of Our Own (AEOO) to unite, educate and economically empower women and minorities.

The discipline of modern economics is usually dated to Adam Smith’s iconic book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. Smith’s upbeat view of the emerging factory system and its purported governing mechanism, the market, still infects economics more than two centuries on. His deification of the market as supreme arbiter and manager, and the subsequent institutionalisation of cost-benefit analysis as its unerring compass, smack of magical thinking, such as Smith’s belief that if each man acts selfishly, an equilibrium of wealth distribution will result.

Yet Smith’s blindness set the key for the UNSNA, which was rolled out across Europe as part of the postwar investment program under the Marshall Plan. It was imposed on the “developing” nations by postwar financial behemoths such as the UN and World Bank, whose investments in their economies required measurability and accountability – and economic measurement and accountability are synonymous with the UNSNA and GDP accounting. Since then, these figures have been used as policy tools to help national governments maximise economic growth, governed by the “Kuznets curve”. This is economist Simon Kuznets’s theory that “income inequality would automatically decrease in advanced phases of capitalist development, regardless of economic policy choices or other differences between countries, until eventually it stabilised at an acceptable level.” Or, as economist Robert Solow put it: “Growth is a rising tide that lifts all boats.” Kuznets later described the thinking behind his Nobel Prize-winning theory as “5% empirical information and 95% speculation, some of it probably tainted by wishful thinking”. And Solow’s “Growth Model” came with this footnote: “One can imagine the theory as applying as long as arable land can be hacked out of wilderness at essentially constant cost.”

In 1988 Waring correctly called these “propagandistic models”. Rickey Gard Diamond and her team at AEOO are contesting this economic sophistry by educating and empowering women and minorities to become agents for change in the public conversation about our money. Gard Diamond says: ‘For us, economics is not just about numbers and the bottom line, but about a gendered system of values that valorises money bullyboys and demeans all things “feminine” including our Mother Earth.’

This is the momentfor redefining our ideas of work itself and its value. It’s time to make unpaid and underpaid care work central to our economy, our global household. It’s time to invest in the structural change required to create an economy that actually values the work that’s essential to sustain us and the ecological systems that make life on Earth possible.

Speaking the wrong language

It’s devastating to learn that what you know to be the real wealth of the planet – not only all that unpaid care work but also the living biosphere – is defined as unproductive and valued at zero. I’ve written extensively about what seems to me the insanity of attempting to include these values in the existing global accounting systems as quantified monetary measures (insane because this economic calculus can never express the infinite value of the Earth’s living systems) – and simultaneously about the horrendous erasures and trashings that go on if we don’t.

In 2014 I explored these issues in Six Capitals through a new accounting paradigm that attempts to address contemporary social and environmental crises by asking businesses to account for four “new” stores of value, or “capitals”, in addition to traditional financial and manufactured capital: intellectual, human, social and natural.

Since then, I’ve been in the uncomfortable position of believing the problems my book addresses, the missing wealth of “people and the planet” and the failure of our current corporate and national accounting systems to value them, are critical issues of contemporary economics – while also fervently believing that the proposed way to address this, by conceiving of this uncounted wealth as “capitals”, is the wrong way to make them count. I state this in my book. But because I named it Six Capitals, its title became a shorthand that effectively erased my reservations and the complexities and alternatives I discuss, giving the idea a kind of iconic resonance that has sounded loud and clear in the global halls of power.

If, as economist Kate Raworth contends, economics is the “mother tongue” of public policy because all policy is expressed in its terms, then the words it utters have material effects. The scale of destruction caused by the language of capital and its casual deployment to describe a unique living forest, an ecosystem’s only source of fresh water, the harried people working for a multinational corporation or the women in a Bangladeshi factory working punitive hours for paltry wages finally tore me apart.

In 2016, I was in Manhattan to speak at the New York Hedge Fund Roundtable’s inaugural sustainability conference – an event itself inspired by Six Capitals. I’d accepted the invitation because I believed that speaking from the heart, or attempting to, in these centres of power might crack open just one mind, one heart. But on that occasion, it was my own mind that cracked, at a morning session where three high-profile investment managers extolled the next sure-fire sustainable source of value, a natural capital.

They called it “blue gold” – and it took me some moments to realise they were talking about water. Not a capital, not gold of any sort. But a priceless, life-sustaining molecule. During that long day, I was filled with an inchoate sense that I was speaking the wrong language, a language that was somehow defaulting me to the wrong side, the side of those financiers who saw water as the next big thing rather than a basic human right.

Their terms are too small for us

For all those years I’d been speaking in my father’s voice, not my mother tongue: that was how I later put it to myself. And by using my father’s voice I was somehow betraying and silencing myself, one of the erased and uncounted in the economic system. But I was versed in economics – and I’d thought I could use its language and logic to demonstrate its own flaws to itself, to expose the omissions in the systems we’d constructed over several centuries.

The problem was right there, with that “we”. There was no we about it. This was an economic system that had been constructed piece by piece, law by law, concept by concept, economic theory by economic theory, over centuries by men.

That day in New York I felt the force of this truth to my core: I’d somehow got trapped in the language of applied patriarchy. My books had plunged me into an underworld of global capitalism where I’d met people in business, government and non-profits, mostly men, who were attempting to deal with a multitude of increasingly obvious social and environmental crises. After five years of listening to their rhetoric and following their initiatives, I realised that although many of them genuinely wanted to care for “people and the planet”, their thinking, language, work and institutions remained locked in a system the default of which is set to privilege money, profits and economic growth at the expense of everything else on Earth.

In January 2020, preparing to speak about the book in Europe and the US, I broke down again. I’d never been reluctant to speak in public before – and now I was positively petrified. As it turned out, Covid-19 postponed these conferences. But looking back now, I think I was scared of betraying myself – and violently – by speaking that old patriarchal language of capital once again.

That was my point of no return. I will no longer speak of those six capitals and of attempting to value “society and nature”, “people and the planet” in their terms. I reject their terms. Their terms are too small for us: too small for all that we are as humans and the Earth’s living systems. I still stand by my book: it does important synthesising, clarifying and narrating work, and it continues to inspire those working within the system – but while the “six capitals” accounting model is an effective diagnostic tool, it is not a cure.

Several months after that breakdown, I agreed to write this essay. Almost immediately, I pulled out. When the editor asked why, I was shocked by the flood of rage and grief this question unleashed – grief from my own experience in the belly of capitalism, and rage at the enormous “invisible” work done by so many countless women over so many, many years. And I found that I was still haunted by my brilliant aunt, Nancy Gleeson-White, whose early promise is written in the clippings that fill my grandmother’s scrapbook. And whose beautiful mind had been erased – sundered – forever, when she was just 45 years old. Nancy embodied the idea of erasure, so terribly and so powerfully, in a family whose lives were shaped by the language and expectations of economics.

A sacred social space

On the day of the Sydney March 4 Justice rally against gendered violence, I looked around at the crush of people of all ages and genders, from grandmothers to babies. It was one of 40 marches across the country that drew an estimated 110,000 people, all mobilised by a tweet from Janine Hendry, who called for a circle of women around our national Parliament House. That massing crowd reminded me, of all things, of the realisation reached by Steve Bannon, arch-right US political strategist and former investment banker, that these global women’s marches are a formidable new political force: “It’s not Me Too. It’s not just sexual harassment. It’s an anti-patriarchy movement. Time’s up on 10,000 years of recorded history. This is coming. This is real.”

I listened to the voices of those women who spoke, the leaders, powerful, undaunted and determined, some of them survivors, whose stories testified more potently than any statistic to the systemic erasure of women – we, who are 51% of Australians – that has rendered us invisible and silent. Aboriginal elder Aunty Shirley gave a welcome to country and described “the systemic mistreatment of Aboriginal women as ‘less than human beings’ since colonisation”, adding that “the historical facts of rape of women … go back to 1788”.

And from within this urgent protest, I saw how a radically reformed economics might look some day. In my vision, economics students sit outside barefoot on the ground, whose touch and smell tell them that this very earth is the matter at hand. They listen to the wisdom of their elders, First Nations women first, welcoming them to country, this land, telling their stories and sharing their wisdom. They learn that economics is the art of managing and caring for the Earth, this planetary household, and therefore for ourselves, all of us, equally; and that the economy is a sacred social space organised around relationships of care.

Just as my own lived experience inside the language and matter of economics has taught me that women and the Earth do count, it’s also taught me that relationships of care, not quanta of capital, are the things that we must maximise. Urgently. Now.

This is an edited extract from Griffith Review 73: Hey, Utopia! edited by Ashley Hay