‘They had a date to kill the cow. So I stole her’: how vegan activists are saving Spain’s farm animals

Spain may be famous for its love of meat – but sanctuaries across the country are coming to the rescue of its doomed cows, bulls, pigs, sheep and geese

In the north-east Spanish region of Catalonia, an enormous bull called Pedro is poking his head over a barn door to look at some sheep. He’ll stay there for two hours if the sanctuary volunteers let him; he’ll have to be tempted away with treats so that the sheep can be let out to graze. Pedro knows the routine; he’s been here since he was a calf, when he was bottle-fed by volunteers. He lives a charmed life – he is fed, he roams, he watches sheep, he sleeps; and when he dies, it will be of natural causes.

“He’s enormous!” I say to Olivia Gomez de Zamora, a veterinary assistant from Madrid who spends a lot of time coaxing Pedro from the barn.

Gomez de Zamora tells me this type of cattle is bred for its milk. “The adult males are slaughtered for meat,” she says. “So we never see them.”

Fundacion Santuario Gaia, where Pedro lives, and El Hogar are two of about 20 animal sanctuaries in Spain where vegan activists dedicate themselves to rescuing animals, creating a place where they can live without being put to work or slaughtered. The employees and volunteers spend a huge amount of time in each other’s company. Some might call it intense: they live and work together, cook and eat together, and there are leisure activities such as movie nights and debates. The sanctuaries are connected via WhatsApp, where they share veterinary information and coordinate animal rescues.

We’re used to seeing dogs and cats saved from abuse or neglect, but at Gaia and El Hogar – around two hours’ drive apart on either side of Barcelona – most of the animals are pigs, cows, goats and chickens. Gaia co-founder Coque Fernandez Abella, 43, an animal rights activist and vet, says: “We wanted it to be for so-called farm animals because they are the most forgotten. No one takes care of them because they’re seen as products.

“Growing up,” he adds, “it was typical to kill pigs to eat at home. Since I was small I had to help with it – it was horrible, because of the screams, but you had to do it. I remember when we rescued our first pig, the memories of the killings came back to me. After everything bad I’ve done in the past, it’s right that I should help animals now.”

The sanctuaries are havens for animals that, rather than being killed for meat or shackled for dairy production, live happily and freely. They are fed and exercised, given medicine if they’re sick, rehabilitated if they’re injured and – the main privilege denied to most farm animals – allowed to live long lives.

Veganism and such care for animals may seem surprising in Spain. Matador directly translates as “killer”. Surely animal-rescuing vegans are an oddity in the land of bullfighting and pata negra?

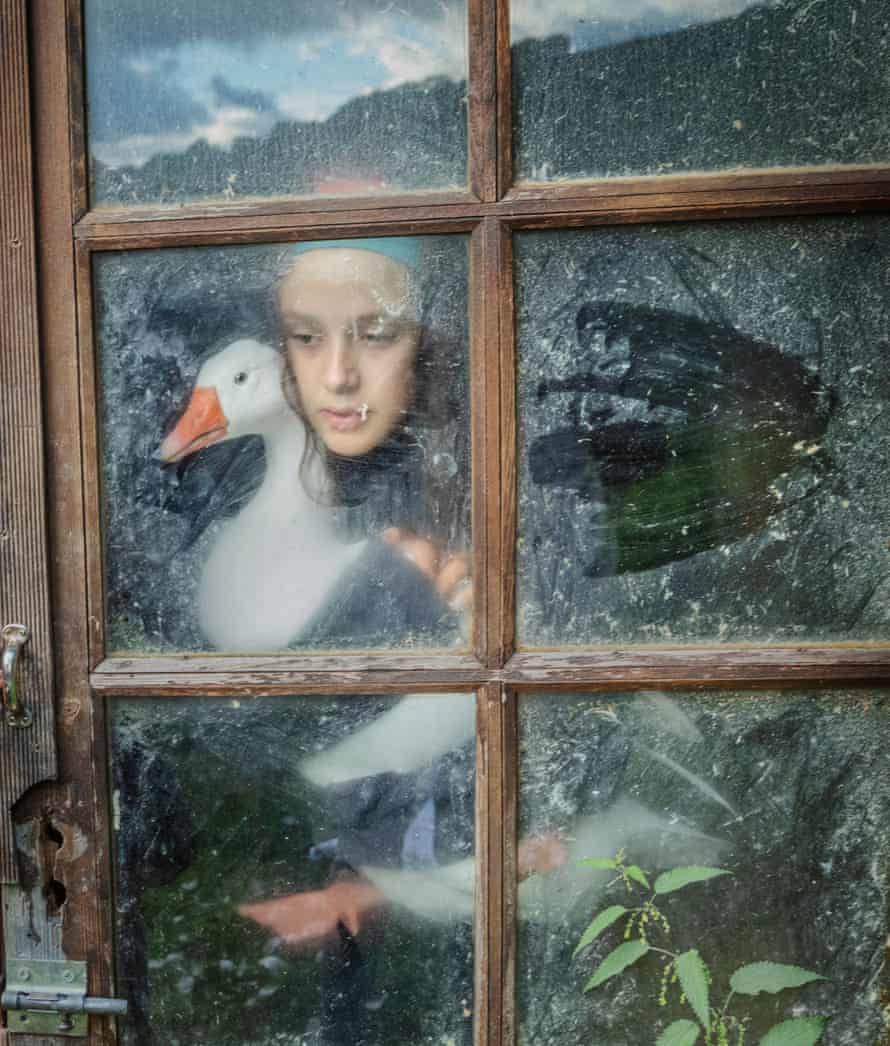

“It’s true we are very much into ham and bullfighting,” says photographer Ana Palacios, who stayed at both sanctuaries for two weeks, capturing their daily goings-on. “But in the UK, you guys hunt foxes!” While the carnivorous tradition is there, especially in the south, “it isn’t that popular among young people,” Palacios says. But veganism is increasing in popularity in many countries – even the ham capital of the world. Between 2017 and 2019, Spanish study the Green Revolution found a trend towards plant-based eating. In 2017, 0.2% of Spaniards identified as vegan; by 2019, it was 0.5%. Vegetarians account for 1.5% of Spain’s population. Animal welfare was the second most common reason cited for going vegetarian or vegan (23.8%) after health (67%).

Gaia employee Marta Sampaio, 24, says her parents were concerned when she made the decision to stop eating meat, aged 15. Now, any time she’s ill, her enthusiastically carnivorous father is convinced her diet is to blame. She travelled to Spain from Lisbon to find a place to work with animals. After training for a few months as a veterinary assistant, she Googled vegan sanctuaries in Spain, and started as a volunteer at Gaia. She found herself empathising, unexpectedly, with chickens. Her first was a chick called Angie, brought in by a girl who found her wandering alone in the road. Because chickens are bred to produce eggs every day, all year round (rather than in cycles of a week or so, two or three times a year), they’re frequently sick. Sampaio has gained a reputation as the “crazy chicken lady” for her habit of taking the sick ones home. “Angie was a baby and didn’t have any brothers or sisters, so she couldn’t be with the other chickens,” she says. “I kept her at home and she slept with me, in the crook of my shoulder.”

Gomez de Zamora left her veterinary assistant job in Madrid to work at Gaia, and stayed for two years. Now back in Madrid, she still collaborates with the sanctuary, but is filled with grief for one animal she cared for there. Her eyes well up and her voice cracks as she remembers Juana the goat, who had a mass on her spine that caused paralysis. “The time I spent with Juana was very beautiful and very painful, because we were aware of her complicated prognosis and that the moment was coming when we wouldn’t be able to do any more,” she says. “It was hard: you had to be OK for her, because her mind was still OK, even if her body wasn’t. You had to make sure she was still enjoying life, and going out in the sun in her wheelchair.”

It’s easy to imagine vegan animal sanctuaries as soft, emotional places, but there is a steely side. Animals aren’t just rescued from the sides of roads: sometimes they’re swiped from state execution. In 2017, the El Hogar sanctuary made headlines after rescuing a bullfighting cow called Margarita.

Margarita had an irresponsible owner. “When he got drunk with his friends, they would chase her on horseback,” says El Hogar founder Elena Tova. “She is still afraid of men.” The authorities discovered he hadn’t legally registered Margarita; under Spanish law, unregistered cows must be killed as without a vaccine record, there is a risk their meat could make people ill, or even cause a pandemic.

“They couldn’t be reasoned with,” says Tova, who explained again and again that she wanted to take Margarita to a vegan sanctuary to live out her natural life; they could guarantee she would never be used for meat. “They didn’t want to change the law or make exceptions. So we created a page on change.org calling for Margarita not to be killed. It got 190,000 signatures in less than a month.” She convinced the owner to let them take Margarita. “But it wasn’t enough: the vets still wanted to kill her. They made excuse after excuse and drowned us in red tape, until a judge who felt for us wrote to me to say, ‘They’re not going to give you the cow’ – they already had a date to kill her. So I went one night, under cover of darkness, and stole Margarita.”

She insists she wasn’t afraid, and points out that the move was technically legal: the owner had signed a contract permitting her to access the farm and take Margarita away, so it wasn’t breaking and entering. But the authorities – whom Tova called next day to explain where Margarita was – were, as she puts it, “super pissed off. They turned up at the sanctuary. Then the press came, and TV cameras – we were on the radio and in the papers.” Eventually, the strength of public opinion forced a change in the law. “Now, in Catalonia, when a cow is unidentified, they can’t kill her.”

Tova was only nine when she began caring for abandoned dogs and cats. She even stole snails and crabs from supermarkets, so they wouldn’t be killed. When her parents refused to allow her to bring any more animals home, she took food to an olive tree where the animals knew to wait for her. But doesn’t it take its toll, this level of care and concern for creatures who are abandoned and abused, who get sick and injured, and always, eventually, die? Yes, she says, it does. “We are very happy, but we have an inner sadness that’s very difficult to get rid of. So you have to be pragmatic, put your focus on the positive things you can change and think about the animals rather than yourself and your feelings.”

Even though keeping their operations running is a constant financial struggle, both sanctuaries are nursing bigger dreams. Fernandez Abella wants to expand Gaia so they can save many more than the 500 animals they’re currently caring for, and hopes their stories will turn more people towards veganism. Tova, at El Hogar, promises to open a small animal hospital onsite “if it kills her”, so terminally ill animals can die in their own home.

As for Palacios, she found herself changed by her time photographing the sanctuaries, almost a year ago. “It was the profound bond between animals and humans that really struck me,” she says. She hasn’t eaten meat since.