‘Nowhere is safe’: heat shatters vision of Pacific north-west as climate refuge

Residents of the region, known for its mild weather, are facing a shifting reality

The recent heatwave that broiled the US Pacific north-west not only obliterated temperature records in cities such as Seattle and Portland – it also put a torch to a comforting bromide that the region would be a mild, safe haven from the ravages of the climate crisis.

Unprecedented temperatures baked the region three weeks ago, part of a procession of heatwaves that have hit the parched US west, from Montana to southern California, over the past month. A “heat dome” that settled over the area saw Seattle reach 108F (42.2C), smashing the previous record by 3F (1.7C), while Portland, Oregon, soared to its own record of 116F (46.7C). Some inland areas managed to get up to 118F (47.8C).

The conditions in a corner of the US known for its moderate, often lukewarm, summers bewildered residents.

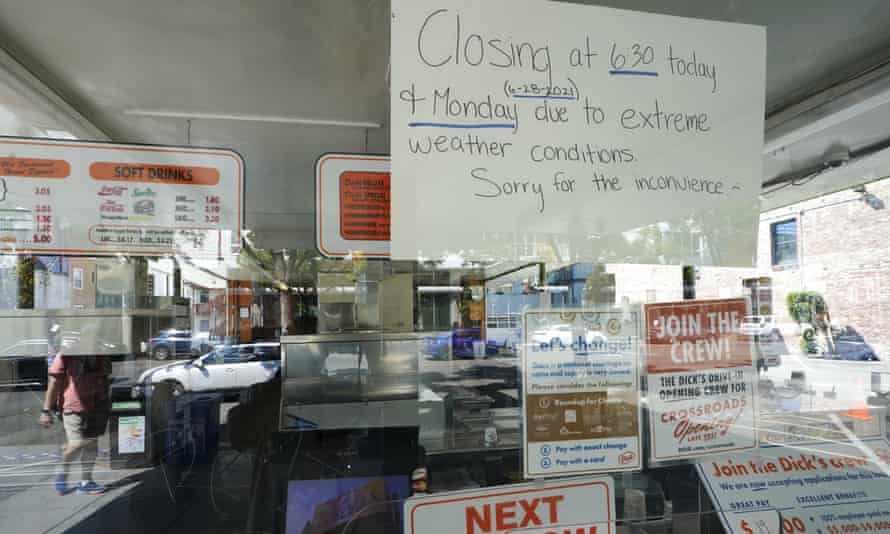

Roads cracked and buckled in the heat, power cables melted, restaurants shut down. Hospitals suddenly found themselves overwhelmed, with several hundred people believed to have died in the heat. Slightly north, off the coast of Vancouver, an estimated 1 billion marine creatures perished, as helpless mussels and clams cooked in their own shells.

“We saw the forecasts and it was hard to believe as we don’t really have heatwaves like that. In Seattle it’s usually so overcast during June we call it Juneuary,” said Kristie Ebi, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington who knew the heatwave was serious when she woke up at 6am with the temperature already at 80F. “You see the heatwaves hit other places and you know it’s bad but there’s not the sense of urgency until it hits you.”

An old joke in Seattle is that you will know more people with a boat than people with air conditioning and the latest figures show just 44% of households in the city are fitted with air con. The Pacific north-west’s image as a place of rugged natural beauty, comfortable climes and forward-thinking politics has helped draw plenty of newcomers – Seattle was the fastest-growing major US city last year – but the freakish heatwave has provided a sobering reality check to its blossoming status as a refuge.

“There are a lot of people moving up from California with the idea there’s a lot of natural amenities and a lot of cheap space but all of these factors are changing,” said Jesse Keenan, an expert in climate adaptation at Tulane University. “It’s becoming less affordable and is increasingly burdened by forest fires, terrible smoke, flash floods and these heatwaves that suddenly make things a matter of life or death.”

The Pacific north-west has heated up by an average of 2F (1.1C) over the past century, with growing wildfires, failing coastal fisheries, receding snowpack and increasing heat taking its toll upon a region historically unprepared for such extremes. The recent heatwave would have been “virtually impossible” without human-induced climate breakdown, scientists have said.

Communities in the north-west face a “monumental task” to adapt to this shifting reality, Keenan said, requiring the upgrading of homes, businesses and public buildings with proper cooling, increasing shade with more tree cover, making urban surfaces more reflective to the heat and retooling an electricity grid ill-equipped for huge power surges in summertime.

“There is a very rapid change in the climate under way and at the moment they are not well prepared for extreme heat,” Keenan said. “People are finally feeling the pain of that.”

Oregon was supposed to be a tranquil haven for Steven Mana’oakamai Johnson, who moved to the state in 2017 after witnessing his home in Saipan, part of the Northern Mariana Islands in the Pacific Ocean, menaced by typhoons made increasingly powerful by the warming ocean and atmosphere.

But when the heatwave struck, Johnson, his partner and their dog had to flee their Corvallis apartment, which does not have air conditioning, to stay on the Oregon coast in an attempt to cool down. The surging heat, which followed wildfires that raged nearby last year, has forced Johnson to revise his previous assumptions.

“I always thought this was a comfortable place, that it could even be a host state for climate migrants,” said Johnson, a biologist. “But there has been this big wake-up that things are moving faster than anticipated. It was shocking how hot it got, and how long it took to cool down.”

Several of Johnson’s friends are among the many people now inundating local contractors with requests to install air conditioning.

“In just a few days you’ve seen this big change in how people are thinking about adapting,” he said. “It has changed my view of Oregon. It’s hammered home to me that climate change is inescapable – no matter where you are or when you go there, you have to think about it. Nowhere is safe, nowhere is truly a refuge.”

The calculus for some people is even more existential. A few hundred miles north of Seattle, the small Canadian town of Lytton was almost completely consumed by a fast-moving wildfire on 30 June, the day after it set a stunning new national record temperature of 121F (49.6C), a huge leap on the previous record and higher than any temperature ever gauged in Europe or South America.

Lytton is located in a more arid inland area than the breezier British Columbia coast and so often gets scorching heat in summer, although nothing approaching the incredible extremes endured this year. It is forcing some to think about their presence in what is supposed to be a safe corner of the world.

“I firmly believe there will be more and more fires until there are no trees here,” said Jim Ryan, a computer programmer who has lived in Spence’s Bridge, a small town near Lytton, for the past 30 years. “Even if I don’t get burned out, do I want to spend every summer living in smoke, in a place more polluted than in the big cities?”

Ash is still falling down around Ryan’s house and in most recent summers a nearby wildfire has choked his town, leaving his clothes smelling of smoke. “There were always fires before, but never this big, they never took off as fast,” he said.

“To me, it is climate change in action. I don’t really want to move away but I don’t want to live here and cut short my life either. That’s something we are struggling with. The question is, though – where would we go to?”