‘Like Uber for snake emergencies’: tech takes the sting out of bites in rural India

Venomous snakebites cause tens of thousands of deaths each year. But homegrown apps are coming to the rescue – and protecting reptiles from reprisals

When 12-year-old Anay Sujith felt a sharp sting in his leg while asleep in his hut in a village in Kerala, “I started yelling and woke up my parents,” he recalls. They immediately sought help – not with a phone call, but through an app.

A team from Kannur Wildlife Rescuers (KWR) reached the boy’s home, in Ramatheru village in the coastal city of Kannur, within minutes and he was admitted to hospital 20 minutes later. He had been bitten four times by a venomous Russell’s viper, one of the “big four” snakes in India responsible for the greatest number of venomous snakebites.

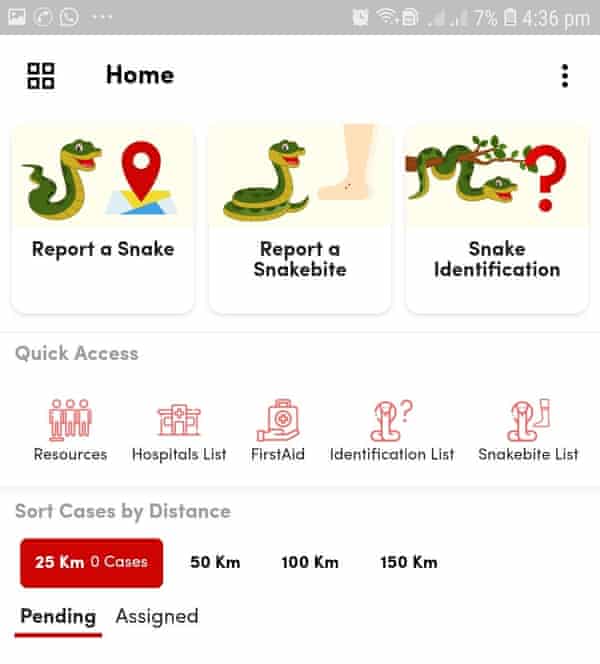

Sarpa (Snake Awareness, Rescue and Protection app), which saved Anay’s life, is one of a growing number of life-saving homegrown snake apps in India that provide information about the ophidians, get people treatment for bites and help doctors to develop antivenoms.

Sarpa, SnakeHub, Snake Lens, Snakepedia, Serpent and the Big Four Mapping Project are among those proving increasingly popular with the public, conservationists and rescuers.

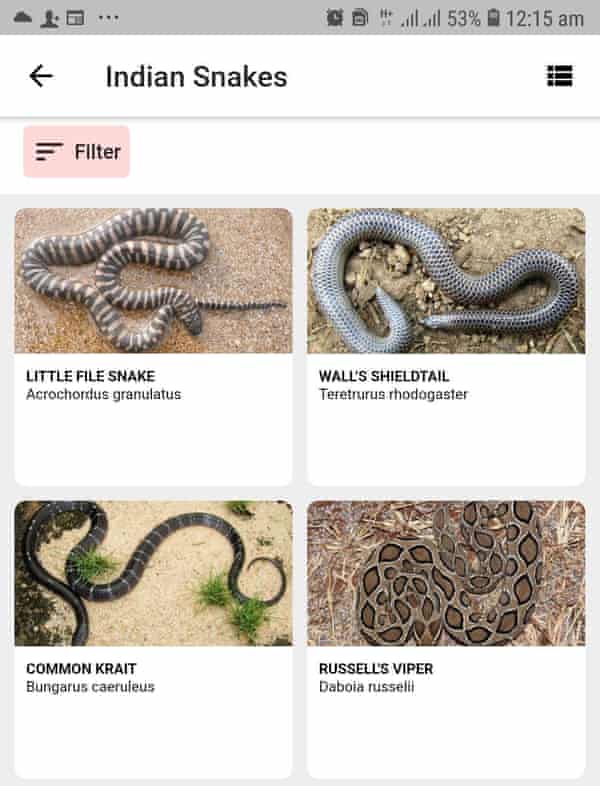

Snakepedia, which launched in February, is an android mobile app that provides information on various snake species, with images, infographics, podcasts and first aid advice for snakebites.

Serpent includes a guide to all of India’s snakes and a search facility to find the nearest hospital that treats bites. It can also connect users in real-time to an expert to help tackle snakebite emergencies. The Big Four Mapping Project, meanwhile, shows reported snake sightings and bites across the country.

“Snake apps are like the Ola and Uber for snake emergencies,” says Jose Louies, head of wildlife crime control at the Wildlife Trust of India, a non-profit conservation group. Louies helped launch Indiansnakes.org, and subsequently the Serpent app. He says apps provide a speedy response to snakebite incidents through a network of volunteers managed by local wildlife departments – which can mean saving both human and snake lives. “This innovative technology helps minimise human-snake conflict and save the lives of both,” he adds.

According to Louies, snakes are at the heart of human-wildlife conflict in India. “India has the highest snake mortality. Just through Sarpa, for instance, we have rescued nearly 2,000 snakes, including 800 cobras, in the first six months of this year. The app gives real-time reports about how many rescuers are out in the field, the number of snakes rescued and other critical data.”

An estimated 1.2 million people died from snakebites in India between 2000 and 2019, the equivalent of more than 58,000 a year, according to a recent paper.

Snakebites are a global health priority, according to the World Health Organization. Between 81,000 and 138,000 people around the world die from snakebites each year, and about three times that number are left with permanent disabilities.

There are about 3,600 known species of snakes in the world, of which more than 300 are found in India, says herpetologist Sandeep Das. “Out of these 300, only 62 are venomous or semi-venomous and only four, or the ‘big four’ – Indian cobra, common krait, Russell’s viper and saw-scaled viper – cause 95% of all snakebite deaths in the country,” he says.

Many snake attacks prove fatal, Das says, because they happen in areas without quick access to medical care. Villagers in the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh are particularly vulnerable, especially during monsoons when snakes and humans are more likely to come into contact, he says.

“Poor farmers, cattle grazers and shepherds moving around barefoot in rodent-infested fields are easy victims. Limited availability of anti-snake venom and expensive treatment put an enormous financial burden on the poor,” he says. “Despite this, snake bites are one of the most neglected diseases.”

Being a rescuer is not without risks, and the Kerala Forest Department has launched a committee to form a set of guidelines. More than 900 rescuers have been trained in identifying snakes and treating bites.

“All rescues are currently happening through Sarpa, which has had 35,000 downloads since its launch last year,” says Louies. “Earlier, there was no record of rescues from snakebites. But now, users can simply download the app and get access to a rescuer available in their vicinity.”

Snake apps are also making it easier for the public and conservationists to work together. Kerala-based conservationist Vijay Neelakantan, who launched KWR, says the collective’s rescuers have been trained in how to respond if a hostile situation arises. “We have 37 certified rescuers who are also conducting sensitisation campaigns among villages about conservation, snake types and what to do in emergencies.

“Currently, a villager’s first instinct is to kill the snake the moment they see it. But we’re educating them that killing snakes is illegal, that they should instead get in touch with certified rescuers who can save the lives of both man and animal. We’re also incentivising the rescuers with a cash reward whenever they catch a snake.”

Snakebites have been traditionally underreported and inadequately treated in India, with poor literacy and a lack of information on how to deal with them aggravating the problem, says Neelakantan. But the apps are helping to change that.

“A snakebite victim can survive for five hours but the golden (first) hour is critical. If the victim gets treatment within this time frame, chances of his survival go up significantly.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features