What does the EU’s carbon tariff proposal mean for Australia?

Trade minister calls the carbon border adjustment mechanism ‘a new form of protectionism’, but experts warn we must prepare

Last modified on Thu 15 Jul 2021 02.53 EDT

The European Union has released details of its long-proposed carbon tariff, inelegantly known as a carbon border adjustment mechanism.

At the same time, US Democrats pulled a surprise by including a tax on imports from countries without aggressive climate change policies as part of a US$3.5tn budget plan released on Thursday Australian time.

Australia’s trade minister, Dan Tehan, attacked the EU proposal before the details were released and again once they were, arguing it could hit jobs and be “just a new form of protectionism”.

But some experts say it is a matter of when, not if, they are introduced – and the Australian government and business community should be prepared.

What is a carbon border adjustment mechanism? Is it a tax?

In simple terms, it is a charge imposed on overseas businesses that make products that lead to greenhouse gases being pumped into the atmosphere but don’t face a cost for them at home.

Countries that have pledged to be more ambitious in combating the climate crisis are looking at imposing greater carbon costs on their own businesses to drive emissions cuts, but they don’t want locally made goods to be unfairly disadvantaged against overseas competitors.

The answer in some cases is a carbon tariff – or, if you like, a tax – charged on some products coming in from countries that are not taking similar steps to deal with climate change.

The idea is not to penalise the overseas companies or – as the Morrison government has suggested – to embrace old-school protectionism. It is to level the playing field so local businesses in countries applying a tariff can compete while this vast global problem is addressed.

It is most commonly referred to by its acronym, Cbam (pronounced: see? bam!).

How does it work?

As part of its sweeping proposals to tackle global heating released on Wednesday, the EU executive said it would impose a levy on some big-emitting import industries.

The first industries to face potential costs include cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertiliser and electricity. Businesses are expected to face reporting obligations from 2023, with the costs starting in 2026.

The idea of carbon tariffs is not particularly new – there have been studies and proposals dating back years – but the global push to cut emissions has accelerated in recent months. All members of the G7 have announced much deeper emissions reduction targets for 2030 over the past year and all Australia’s major trading partners in Asia have set net zero goals for either 2050 or 2060.

As explained above, the goal of the EU proposal is to avoid emissions cuts on the continent being undermined when it brings in goods from countries that are not acting on climate in the same way. The bloc has set a target of cutting emissions by 55% cut compared with 1990 levels by 2030.

It would require EU-based businesses that import goods to pay a price linked to what they would have paid if the items had been produced under the EU’s own emissions trading scheme.

The rationale is if it didn’t go down this path there would be a risk of “carbon leakage” – local production shutting down and moving to countries without strong climate policies. Obviously enough, this would do nothing to cut global emissions.

Revenue raised from the charge would be largely used to help pay for the EU’s green transition. Deductions will be offered to importers if the non-EU producers can show they have already paid a carbon price for the production of the goods in another country.

That’s a difficult case for Australian companies to make – the Coalition repealed Australia’s carbon pricing scheme in 2014 and has not introduced anything substantial to replace it.

The EU has pledged its system will comply with World Trade Organization rules that aim to ensure fair treatment for all.

The European plan has been kicking around for a while. The commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, proposed a Cbam as part of a green deal put forward in 2019. The plan was strongly endorsed by the European parliament’s environment committee earlier this year.

The tariff will not apply to industries that do not currently face a carbon cost under the EU emissions trading scheme, such as agriculture. But that could change as steps are introduced to make deeper emissions cuts in the years ahead.

The current EU carbon price is more than A$80 a tonne of emissions – more than three times what Australia’s carbon price reached before it was repealed in 2014 amid bad faith claims about its catastrophic impact.

What about countries outside the EU?

There have been growing signs that other countries are planning to head down this path. There have also been signs of pushback against the EU’s plans.

At a meeting in Cornwall last month, the G7 leaders pledged to work collaboratively to prevent carbon leakage by “align(ing) our trading practices with our commitments under the Paris agreement”. They backed the introduction of carbon pricing policies to help decarbonise their economies.

The agreement was non-binding, but in step with a British government push for stronger global action on climate change in line with what scientists say is necessary ahead of the Cop26 major climate conference in Glasgow in November.

In the US, Biden’s election platform included a commitment to introduce a “carbon adjustment fee against countries that are failing to meet their climate and environmental obligations“. There has been little detail of what that might mean, but leading Democrats made headlines on Thursday morning Australian time when they included the possibility of a “polluter import fee” – a carbon border tax – in their budget plan.

Quick GuideHow to get the latest news from Guardian AustraliaShow

Email: sign up for our daily morning briefing newsletter

App: download the free app and never miss the biggest stories, or get our weekend edition for a curated selection of the week’s best stories

Social: follow us on YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or TikTok

Podcast: listen to our daily episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or search “Full Story” in your favourite app

They released few details of what they had in mind – there was no explanation of what would be taxed or how much revenue would be generated – and it is far too soon to know whether it could pass Congress. The New York Times reported that some lawmakers believed a carbon border tax could appeal to Republicans and Democrats opposed to climate action if it could be demonstrated it would address concerns that other countries would have an unfair advantage as the US cut emissions.

The Biden administration has previously said it welcomed discussions on policies to address carbon leakage, but expressed concern that the EU proposal was focused on whether a country had an explicit carbon price and did not assess the impact of other climate policies.

Other countries have been vocal in raising concern about the EU plan. China, South Africa, Brazil and India issued a joint statement in April expressing “graver concern” over what they described as discriminatory trade barriers.

But there have been signs other countries are looking at going down this path. The Nikkei newspaper earlier reported that Japan was looking at introducing one.

The EU documentation says a carbon border mechanism is already in place in California, where a cost is applied to some electricity imports, and that “a number of countries such as Canada and Japan are planning similar initiatives”.

Is it aimed at Australia?

Not specifically. It appears mainly designed to deal with emissions-intensive goods from emerging economies, notably China and India.

But to stand up under the WTO, these mechanisms will need to be applied equally, so don’t expect Australia-specific exemptions.

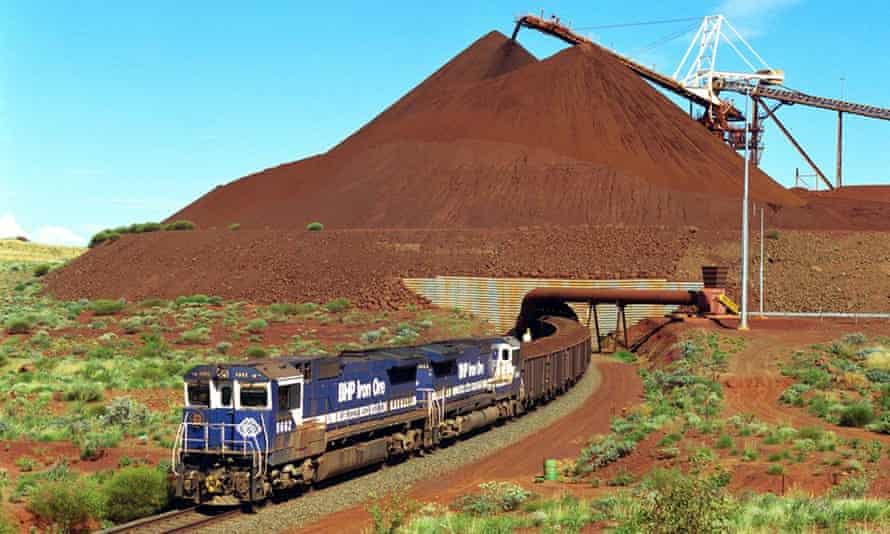

Trade figures show Australia exported $11.7bn worth of goods to the EU in 2019-20. Major exports include coal for steelmaking ($2.7bn), gold coin ($689m) and gold ($409m).

But Australia is not listed in the top-10 exporters in the sectors initially covered by the carbon border adjustment mechanism. China, Russia, Turkey and Britain are the top exporters of iron and steel to the EU.

What will it mean for Australian government and business?

If introduced as written, analysts at the Australia Institute say the policy will have a direct effect on Australia as it exports a small amount of iron to the EU, and have an indirect impact as Australia provides goods to countries that may be hit. For example, it sells alumina to Mozambique that is smelted and exported to the EU as aluminium.

But the impact will be relatively small. Tennant Reed, a carbon policy expert at the Australian Industry Group, says the cost on some goods is likely to be much less than expected under an earlier draft as the latest proposal excludes what are known as “scope 2” emissions (those released in the creation of the electricity used to make the product).

This will cut the cost of importing aluminium, which is sometimes described as “congealed electricity” because it is so energy intensive to make.

Coal exported to the EU for use in steelmaking could be affected, but the actual cost would likely be quite small as the EU scheme does not cover “fugitive” methane emissions released during coalmining.

If Japan was to follow the EU’s lead it is possible some industries could be affected – agriculture, for instance – but coal and gas exports are less likely to be charged. Japan overwhelmingly relies on imported energy and there is very little local fossil fuel extraction to level the playing field with.

In the case of the US, aluminium imports could be affected if Biden and the Democrats follow through on their pledge.

But in the short term, the most clear impact if countries make good on their emissions pledges will be shrinking demand for Australia’s fossil fuels and carbon-intensive goods.

Planning for that – and a world in which the global community expects the cost of emissions to be reflected in government policy – may be a good idea.

.png)