‘People don’t have time to search’: how clear instructions could help Australians recycle better

Most of us believe that recycling is important – but many find figuring out how to do it properly confusing

Here’s a fact you can reuse again and again: it turns out a majority of Australians love recycling, and the best way to empower them to recycle properly is to – shockingly – tell them exactly how to do so on a product’s packaging.

A study by the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation and the environmental organisation Planet Ark found that 76% of Australians think recycling is the most positive thing they can do for the environment. More than half of respondents said the first place they turned to for information about how to recycle is the product’s packaging.

But it’s rare to see step-by-step recycling instructions printed on the side of a jar of pasta sauce, or underneath the care instructions on a new dress, with 48% of consumers agreeing with the statement: “Knowing what I can and can’t recycle at home is confusing.”

Planet Ark’s deputy chief executive, Rebecca Gilling, says a lack of clear labelling creates “twin problems”.

The first issue is sometimes termed “aspirational recycling” – where consumers optimistically contaminate their recycling with non-recyclable materials in the hopes that they can be reused.

“The other thing is that when people don’t know what they’re doing, they often put valuable recyclable materials into their waste bins and they end up in landfill,” Gilling says. Both problems “are based on people’s lack of awareness about how to recycle properly. And this is where the label is so valuable.”

That isn’t to say there aren’t companies paving the way forward.

Courtney Holm, founder of ABCH, an Australian circular fashion label, says it’s important for brands to go an extra step because “people don’t have time to search for generic information”.

Holm hopes to combat the garment industry’s “make, wear, discard” model of clothing consumption. Whenever someone buys one of her garments, the brand emails the customer a guide to looking after, recycling and even composting their purchase. All of this information is also on the company’s website, making it accessible for anyone who comes across one of their garments secondhand.

She says typical recycling information is “very scattered”. “It’s not organised in a way that people who are busy can understand or collect very easily.”

“As a consumer myself, I have this great pair of sustainable sneakers. But what do I do with them now that they have fallen apart and they aren’t able to be repaired? And the answer is always landfill.

“If I had some instructions with my sneakers that said what to do to recycle them, I would absolutely do it. But I would struggle to research and find who is recycling shoes in Melbourne at the exact moment.”

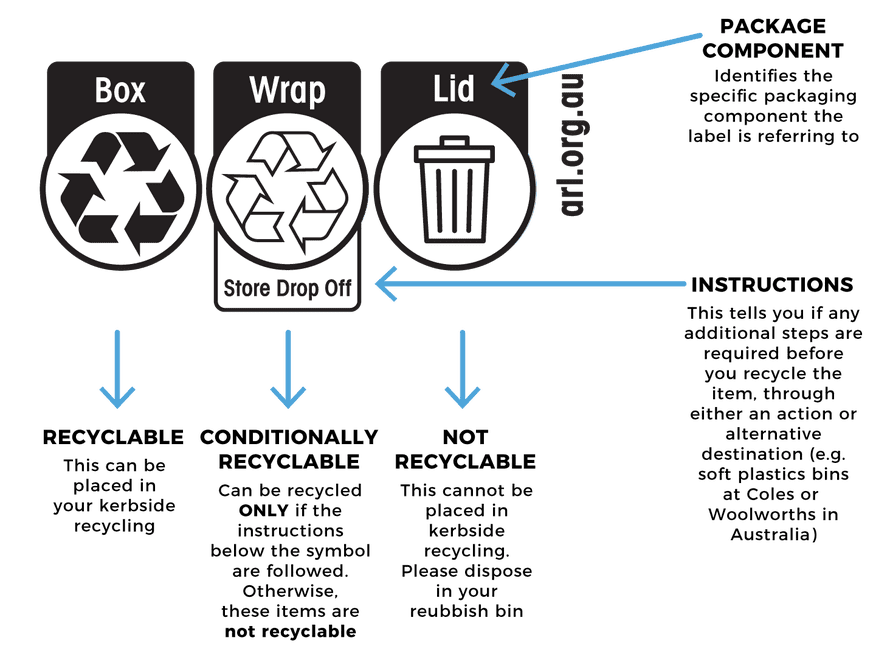

For packaging, the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation has created the Australasian recycling label which brands can add to their products to more clearly identify the different components and how to dispose of them.

Developed in 2018, the label lists the components or materials used in the packaging – for example, the box or the lid – along with a symbol to show whether it should be recycled, thrown out or specially recycled – for instance via a soft plastics collection bin. The program has been adopted by about 400 organisations, including Woolworths, Nestle and T2.

But Rebecca Sullivan, co-founder of Warndu – an Indigenous-owned sustainable food and lifestyle brand – cautions that smaller businesses can face considerable barriers when it comes to making sustainable packaging choices.

Warndu has taken every effort to make its products and packaging as environmentally friendly as possible. Its tea canisters are cardboard and 100% recyclable; its spice packets are soon-to-be compostable; and its range of home and body products are plastic-free.

But Sullivan says that well-meaning small businesses, like Warndu, can struggle to find and afford the most sustainable packaging options when starting out, given their scale and budget.

“We started out just making tea,” she says. “We spent months trying to find a tea bag that was as sustainable as we could. We couldn’t afford to go and have them produced in a factory where you had to do a minimum run of 3,000 of each flavour.

“So we just filled all of our tea bags ourselves and used the bloody hair straightener to seal them. We had to get paper tea bags sent from America because we couldn’t find anyone in Australia that we could just order 1,000 from at a time, and we couldn’t afford to order any more than that.”

While Sullivan thinks consumers should have more information about how to better recycle, she points out that “there’s only so much space on a product”.

“We have so many rules and regulations we already have to abide by, you know? We have to have grams, we have to have nutrition labels, barcodes, Australian made or not Australian made. You have to have a beautiful description and a marketing story, your price,” she says.

“And you add … giving directions for people on how to dispose of it. Is that the producers’ responsibility or is that the consumers’ responsibility?

“We all have to make an effort and we can’t blame anyone for this … I think that the onus has to be on everyone. You know, we’re all part of this world together.”