The battle for Mount Rushmore: ‘It should be turned into something like the Holocaust Museum’

The national memorial draws nearly 3 million visitors a year – and Native Americans want the site back with a focus on oppression

Mount Rushmore national memorial draws nearly 3 million visitors a year to its remote location in South Dakota. They travel from all corners of the globe just to lay their eyes on what the National Park Service calls America’s “shrine of democracy”.

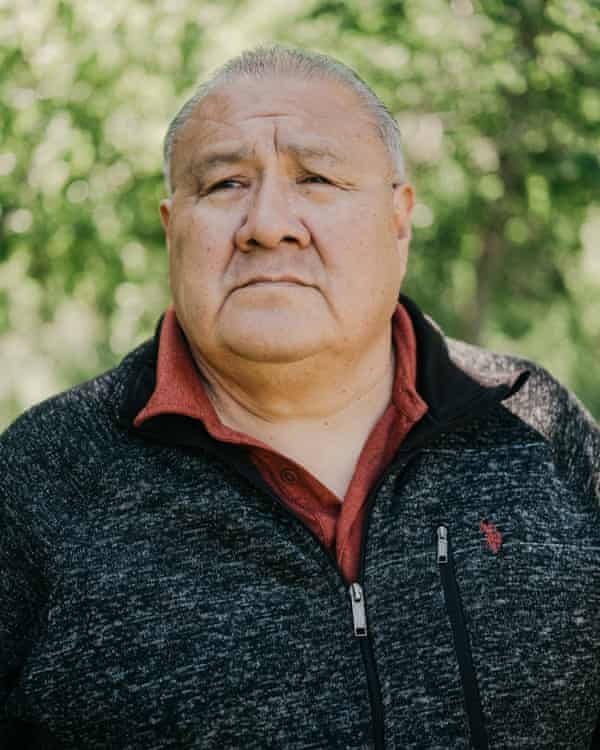

Phil Two Eagle is not opposed to the fact that the giant sculpture of American presidents is a major tourist attraction but he thinks the park should have a different focus: oppression.

“It should be turned into something like the United States Holocaust Museum,” he said. “The world needs to know what was done to us.”

Two Eagle noted what historians have also documented. Hitler got some of his genocidal ideas for ethnic cleansing from 19th and early 20th century US policies against Native Americans.

Two Eagle is Sicangu Lakota and a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota. He directs the tribe’s treaty council office which fights to claim sovereignty over lost homeland. He is part of a growing indigenous movement across the US and Canada that is demanding the return of Native American territory seized through broken treaties. And ground zero for the movement is Mount Rushmore.

Opposition is already proving staunch. Yet while Native Americans have been fighting to get their lands back for centuries, indigenous activists say real progress finally seems possible now that Deb Haaland, a member of Laguna Pueblo, is secretary of the interior. As the first Native American to hold a US cabinet position, Haaland oversees 450m acres of federal land – all of it indigenous territory and much of it stolen through broken treaties.

“Having Haaland heading up the Department of Interior is a game changer,” said Krystal Two Bulls, who is Oglala Lakota and Northern Cheyenne and director of NDN Collective’s Land Back campaign, an initiative demanding that governments honor their treaties with Indigenous people. “It opens the door for beginning the healing process. Returning our land is the first step toward reparations.”

Mount Rushmore is located in the Black Hills, a nearly 2m-acre expanse of fertile forests, creeks and rocky outcrops that is sacred to the Lakota. The Black Hills is the place they call “the heart of everything that is”. After decades of fighting to keep European immigrants out of their homeland, the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota people reached a settlement with the US government and signed the Fort Laramie treaties of 1851 and 1868. The agreements established a sovereign 35m-acre “permanent home” for the Plains tribes called the Great Sioux Nation that occupied the entire western half of South Dakota, including the Black Hills.

But in 1874, Lt Col George Armstrong Custer led a survey party into the Black Hills without permission from the tribes and discovered rich gold deposits. Rather than abide by its treaties, which the US constitution calls the “supreme law of the land”, the federal government allowed gold prospectors and settlers to overrun the Black Hills and surrounding area.

Members of the Great Sioux Nation were forced to surrender most of their territory and move to much smaller reservations on what was deemed useless land by the US government. Decades later, the busts of four US presidents – two slave owners and two who were hostile toward Native Americans – were chiseled into the holy mountain the Lakota called “Tunkasila Sakpe”, the Six Grandfathers.

Based in Rapid City next to the Pine Ridge reservation, the social media-savvy NDN Collective was energized by last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests and resolved to launch a similar campaign promoting the return of indigenous lands. That effort suddenly accelerated when Donald Trump showed up at Mount Rushmore on 3 July last year for a fireworks-studded re-election rally.

NDN Collective organized a protest that blocked the road to the park, claiming the rallygoers were trespassing on sovereign lands of the Great Sioux Nation. Indigenous activists wore eagle feathers, beat drums and faced off with a line of air national guard who were dressed in riot gear. No physical violence broke out but the assembly was deemed unlawful by the county sheriff and 20 activists were arrested. Videos of the protest went viral and so did the “#landback” hashtag along with NDN’s demands for returning the Black Hills and closing Mount Rushmore, which the group described as “an international symbol of white supremacy”.

Meanwhile, inside the park, the former president told his cheering base what they wanted to hear. “Our nation is witnessing a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values and indoctrinate our children,” he said, referring to the recent removal of Confederate monuments. The crowd chanted “USA! USA!” in response.

Elise Boxer, who is Dakota and a professor at the University of South Dakota where she directs the Native American Studies program, said the request for the return of homeland is largely misunderstood by non-indigenous people. “It is not about owning the land. It is about regaining a spiritual relationship to the land,” she said.

The memories of frontier settlers engaging in bloody battles with Native Americans are still raw in South Dakota, Boxer said. The Black Hills are the ultimate symbol of that racial tension. “If our land is returned, there is the fear by non-indigenous people that they may be treated in the same way the early settlers treated us,” she said. “And there is also a very paternalistic belief held by the government that Natives can’t take care of their own land.”

Deciding who has a rightful claim to the Black Hills is actually already settled according to a 1980 supreme court ruling in the case United States v Sioux Nation of Indians. “A more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealings will never, in all probability, be found in our history,” stated the court’s majority opinion that agreed the Black Hills had been stolen from the Sioux. The court’s solution was to financially compensate the tribes for the land with an award of $2m. However, the tribes insisted the Black Hills were not for sale and they refused the payment. The award has been held in trust and now totals nearly $2bn with interest but the Lakota and other Sioux tribes, who live in some of the poorest areas in the United States, will not accept the money in exchange for their sacred lands.

“We are poor because our resources were stolen from us and those resources made others billions of dollars,” said Red Dawn Foster, an Oglala Lakota and South Dakota state senator representing the Pine Ridge reservation. “But our connection to the Black Hills is not a monetary one. Our main concern is that the land not be desecrated and we be allowed to resume our role as stewards of the land – that is our purpose as Lakota.”

Foster said many of the “social ills” experienced by the Lakota are rooted in the loss of their spiritual connection to the Black Hills and being denied access to sacred sites for ceremonies. She said the Sioux tribes are simply asking for a “transfer of stewardship”, so the Black Hills would no longer be managed by the US Forest Service or Park Service but by the Great Sioux Nation.

Putting Mount Rushmore, along with the rest of the Black Hills, under Native American management is a realistic first step for addressing the harms of colonization, she said.

Corbin Johnson, until recently the mayor of the tourist-dependent town of Custer located in the middle of the Black Hills, is not thrilled about this idea. “Why don’t the people in other places give their land back?” he said of non-indigenous supporters of NDN’s campaign. (Johnson’s term ended 30 June.) “This whole country is on indigenous territory, so where does returning land start and where does it end?”

Johnson has lived in Custer county his entire life and finds the Black Hills “magnetic”. His wife’s family moved to Custer in 1875, the year after the United States broke the treaties and allowed European immigrants to establish homesteads. “I understand the motivation for the land back thing but how do you make it work?” Corbin asked. “Figuring that out goes way beyond me or my town.”

With a Democratic president and Congress in power as well as a Native American woman overseeing federal lands, Daniel Sheehan, chief counsel for the Lakota People’s Law Project, is hopeful steps will be taken to finally address broken treaties.

Since Haaland was sworn in in March, her department has transferred 18,800 federal acres comprising the National Bison Range in Montana to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, where the land will be held in trust for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes. And Haaland has reportedly recommended to Joe Biden that the boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument be restored to their original size in order to protect numerous Native American cultural sites.

Sheehan said there are various legal mechanisms for returning control of Mount Rushmore and the rest of the Black Hills to the Sioux tribes such as passing a bill in Congress or executive action under the 1994 Indian Self-Determination Act. Mounting public pressure also plays a big role. A petition sponsored by NDN Collective requesting the closure of Mount Rushmore and return of public lands in the Black Hills currently has more than 44,000 signatures.

Meanwhile, the staff at Mount Rushmore is attempting to carry out its mission of celebrating the “shrine of democracy” but also incorporate Native American culture as part of the visitor experience. “We strive to provide a broad spectrum of history and messaging,” said the Mount Rushmore chief of interpretation, Maureen McGee-Ballinger. She noted there is a “Lakota, Nakota and Dakota Heritage Village” interpretive display along the park’s main trail. It is staffed by a fifth-generation grandson of the celebrated Oglala Sioux warrior Red Cloud. The current setup is a long way from what Phil Two Eagle envisions possible with a transformed monument that documents Native American genocide.

“After 500 years of injustice, you can’t just put up a fake village manned by a token Indian and say, ‘We’re good,’ ” said Two Eagle. “We want to meet with Biden and ask him to honor the treaties. We want to find out what he will do to stop the ethnocide of our people.”

After the Fort Laramie treaties were abandoned in the wake of the Black Hills gold rush, the Lakota called the US government “”, which means “takes all the fat”. Navajo author Mark Charles sees the current battle for the Black Hills as a chance for Anglo Americans to turn that paradigm on its head.

“The United States has historically viewed everything through the lens of exploitation and profit,” he said. “But indigenous people are trying to teach a very young nation a different way of being. We want white Americans to learn that life has so much more meaning if they can just see past the dollar sign.”

.png)