“Oma, hoi! Hier! Hallooo,” Dr Kees Scheepens, a Dutch farmer known as the “pig whisperer”, is calling his two oldest pigs for some apricot snacks.

Oma or “granny”, a seven-year-old sow, lives with a Berkshire boar called Borough, who’s nine, off a quiet lane in the town of Oirschot, in the south of the Netherlands, on a farm called Hemelrijken – Dutch for “the realms of heaven”.

Scheepens, 61, says he is the 19th generation of farmers in his family, and that after years practising as a vet, he is driven by an unusual set of ambitions: “emancipating” farm animals, putting animal welfare first, and eating far less, far happier meat.

“Borough and Oma are here to stay,” he says, squelching to his farthest field, where the two 400kg-plus animals squeeze into their shed. “I’ve given them a name and when you give a name to a pig, I cannot butcher it any more. I had three boars, David, Att and Borough. David and Att are already in heaven but ‘Bro’ is still here.”

As he walks around feeding and talking a little French to his 28 sows (according to Scheepens, “neuf“, is their grunt of confirmation, and “huit, huit” is them asking for more) the place seems idyllic. The pigs are fed on produce being thrown away by organic supermarket Ekoplaza: boxes of white cabbages, slightly wilted beans, veggie-balls, 500kg of Canadian lentils, overripe mangoes from Burkina Faso, hundreds of tubs of peach mango soy yoghurt, and boxes of apricots. A couple of cats and dogs wander around. Meanwhile, in a forested nature reserve area, 45 Angus cows have just calved.

Scheepens primarily raises a breed he calls the “Duke of Berkshire”, a cross of the hairy Berkshire pig and white sow, named with a nod to his years working in England. Although he raises them for meat, he is passionate about animal welfare. “Am I rich in money? No, but I’m primarily motivated by emancipating farm animals.”

He started his pig project almost a decade ago, aiming to help bring open-air farming back to the muddy Netherlands, and pioneer a new type of barn farming.

“Factory farming of pigs in the Netherlands is a dead end,” he says. “We now know that a pig is not a thing: it is a sentient being with a high level of intelligence, comparable with the intelligence of a child. What I see worldwide is that many pig farmers don’t know any more what pigs are about. They just don’t have the skills to know what’s right and what’s wrong.”

What’s wrong, he believes, is factory farming where cannibalistic “vices” such as tail biting replace normal pig behaviour such as rooting around for food. This leads to widespread “tail docking” in many parts of Europe to stop animals eating each other’s tails, even though the practice is banned.

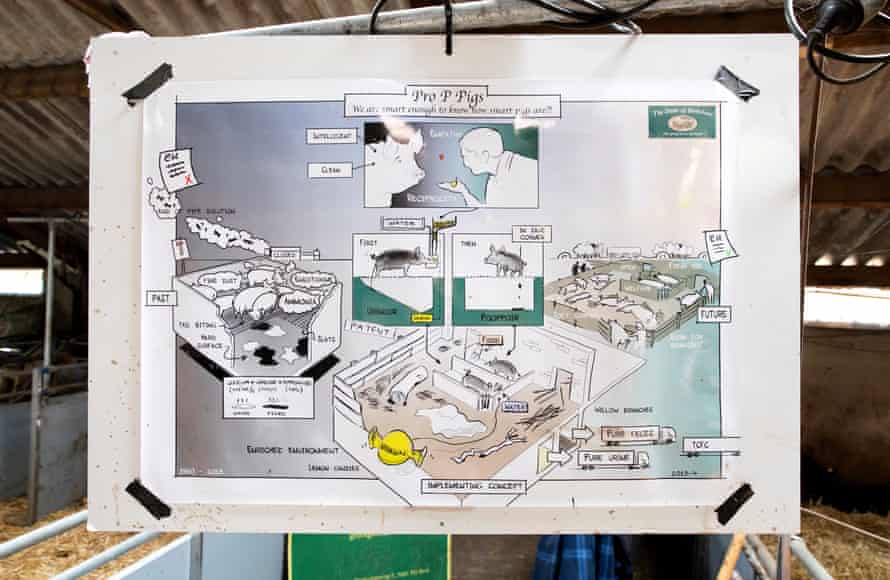

Instead, Scheepens argues, pigs need a more natural environment, to be able to root around in beds of straw or wood chips and have outdoor access, with a special toilet replacing slatted floors (where urine and faeces fall through and mix).

“I would say pigs are the most hygienic animals we have on the farm,” he says. “They will not poo or pee in their nest. Pooing always goes well: their noses are so sensitive, they recognise the smell.”

To encourage them to urinate separately, he has created a reward system: a machine delivering lemon sour candies when their urine goes through a special floor membrane in an outside “toilet” area.

Why is peeing important for sustainable farming? “When I reward them for correct urinating, there will not be the contact between a nitrogen compound found in urine and an enzyme in the manure: that creates ammonia, and that’s one of the main factors in the [excess] nitrogen discussions [taking place] in the Netherlands.”

Scheepens believes animal cruelty at abattoirs and intensive farms cannot last; his own turning point came after the swine flu epidemic of 1997-98, when he was forced to euthanise about 10,000 newborn piglets.

“At the time I just did my job. But later on, I developed very serious epileptic seizures. I said to myself: ‘You have euthanised healthy pigs. As a vet you are trained to cure animals that are sick or to keep animals healthy, not to butcher piglets.'”

Returning from a period working in England, during which he was diagnosed with epilepsy, he decided he wanted to be a farmer like his forebears. “I think when you want to work with animals and have them play a role in agriculture, it has to be sustainable,” he says.

“Meat has become a throwaway product, where the true value is not seen any more. Wouldn’t it be nice if farmers were offered an income with the same farm and half of the animals? Sustainability can only be there in my perception when you take care of animal welfare first.”

The Netherlands is a densely populated country, and the land is often poorly drained. So as well as outdoor farming, Scheepens wants to revolutionise animal barns so smells and emissions are reduced, and pigs can laze, eat, root and wallow as nature intended.

“The last three to four generations have started using fertilisers, pesticides and going from big, bigger to biggest,” he says. “That was the societal trend in agriculture, but I think we have to become smartest. I don’t want to have a grandchild saying to me: ‘you broke that tradition of farming because you destroyed the Earth.'”

He thinks there’s no need for pig farming to stink: “I always say to farmers, you can just ignore what we gained in knowledge on animal welfare because your barn needs to be paid off. But the mental and emotional reasons to change are huge. In every farmer, there’s also a heart.”

Sign up for the Animals farmed monthly update to get a roundup of the best farming and food stories across the world and keep up with our investigations. You can send us your stories and thoughts at animalsfarmed@theguardian.com