Joe and Mario Duplantier grew up in a calm idyll – perhaps surprisingly for two of metal’s most forthright rabble-rousers. Born to a sketch-artist father and yoga teacher mother, the brothers were raised in Ondres, a remote commune on France’s western coast. Their house was so rural that, when a journalist visited, he compared it to a “hermitage”. Music was always playing, from folk to Mike Oldfield; it only stopped when poets and painters stayed the night and the children overheard the grownups discussing international philosophies.

The pair often passed the time on the beach. Joe collected wood and stones – only to come home to find his hands black with crude oil. Mario, meanwhile, had plastic bags flying in his face when he was out surfing. The serenity of the fairytale upbringing cracked. “We were confronted by nature hurting all the time, and nature hurting hurts you,” says Joe, the elder brother.

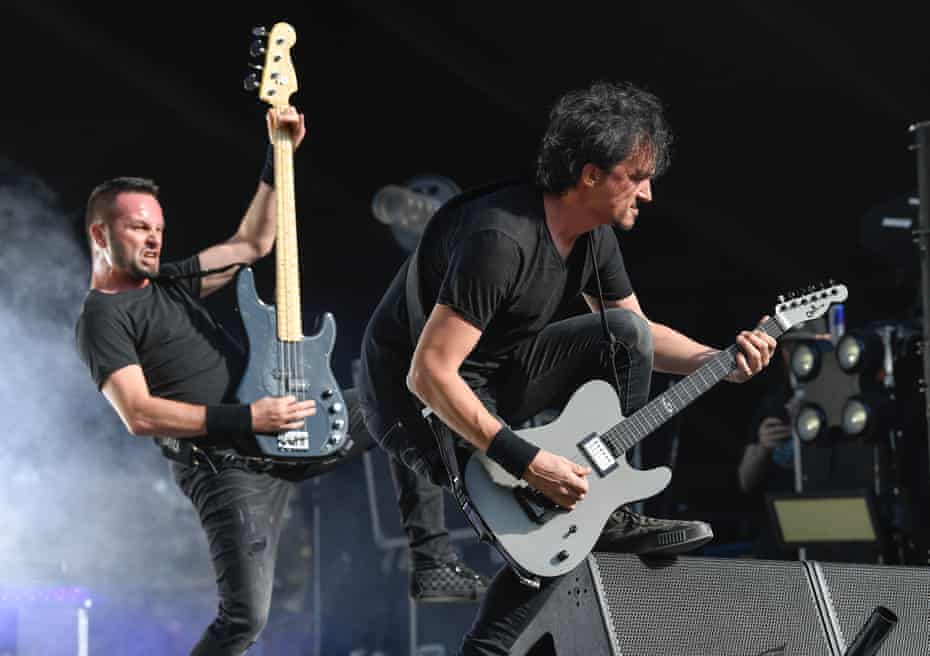

The Duplantiers vocalise that hurt in Gojira, an extreme metal quartet loved not only for their musicianship – rampaging and intricate – but also their environmentalist outcries. “The greatest miracle is burning to the ground,” Joe shouts on Amazonia. A single from the new album, Fortitude, it is a grooving monster that laments the destruction of the rainforest. (All proceeds from the track go to a charity for tribes who have suffered through deforestation.)

Joe says that – amid the bleak imagery – Gojira want Fortitude “to express something that would empower people and inspire them”. He dubs it a call for “civil disobedience”, designed to invigorate listeners into action. The anthem Into the Storm could soundtrack a revolution with its countercultural lyricism (“You’re awake now! Put your fist in the air!”) and Mario’s marching drums, while Born for One Thing begs us to look up from our phones to a wounded world. “Who are we to say if humanity is worth continuing?” the vocalist asks. “I think having hope for the future is a default setting that we have. We choose to be in that energy that wants to succeed – if everyone says: ‘We’re not gonna make it,’ we’re not gonna make it!”

Despite their youth surrounded by creativity, Joe and Mario were not brought up to be metal’s next sociopolitical visionaries. Hard rock was the only thing their parents never played on the radio. It wasn’t until the brothers’ cousin “forced” Joe to listen to Metallica that it clicked. Mario, then 12, also got hooked: “It was just the vibration, the tone, the drumming – it was mystical.”

Joe adds: “I think metal attracts sensitive people. I was born sensitive, bullied in school – I hated humans. The themes are very emotive, and there’s a traumatised aspect that attracted me.”

Its rage energised the pair to emulate their heroes, with Joe picking up the guitar and becoming a singer. “For me, it was never a thing to preach or have a message,” he says. “It’s music that comes from the guts. I’m yelling into a microphone. The yelling made the important words come out. I’m not gonna yell about the last pizza I had.” Mario – a fiery and extroverted youngster – fell for the drums. “All my friends at school played rugby, but I didn’t like it; drumming was my rugby. It was my way of expressing myself with my body,” he says.

Gojira formed in 1996, when the two put out an ad looking for musicians inspired by the band Death. Through that came the second guitarist, Christian Andreu; later came the bassist, Jean-Michel Labadie. The four called themselves Godzilla – there is nothing more metal than a fire-spewing kaiju – before switching to the Japanese translation.

They self-released their debut, Terra Incognita, in 2001. Moulded by the conversations the Duplantiers listened in on as kids, its title alludes to Hindu mythology, specifically the unknown place where Brahma hid godhood from humanity after their abuse of its power. The 2003 follow-up, The Link, was similarly metaphysical, pondering resurrection, meditation and enlightenment through suffering.

“The music was more spiritual at first,” says Mario. “There were a lot of metaphors and [philosophical] images. When we released From Mars to Sirius in 2005, we stayed poetic, but a song like Global Warming was something truly important to our environmental message.”

With its sci-fi narrative about humanity depleting the Earth and searching for another home, From Mars to Sirius was Gojira’s first climate-crisis-oriented outing, as well as their international breakthrough. Its bold take on death metal balanced breakdown-laden juggernauts such as Backbone (which remains one of the heaviest things ever composed) with spaced-out epics, built on tapped guitar playing and serene vocal passages.

“We were ready to conquer the world!” Joe exclaims. “We had so much energy and we weren’t scared, tired or bored. After 10 years of grinding and working hard, we were on fire – so ready and hungry to meet new audiences.”

That piss and vinegar flowed through The Way of All Flesh and L’Enfant Sauvage, both of which refined Gojira’s abrasive sound. The band frequently tour the US and Europe and their live shows are meticulously perfected by watching videos of themselves back every night – “something every musician should do”, Mario says.

That unyielding lifestyle shaped the sixth album, Magma, in 2015. “When you’re a musician, touring is 90% of your life,” the drummer says. “For weeks, you screamed every night and your body is struggling to go back to normal. It’s the best job in the world and the most painful. That has a huge impact on the way you write. You won’t be able to play crazy, violent, fast for ever.”

The songs were hugely simplified, each built around one or two riffs. Classic verse-chorus-verse-chorus structures became more prevalent and the delicate potential of Joe’s voice was emphasised further, crafting a meditative mood. That tone was consolidated after the Duplantiers’ mother, Patricia Rosa, died that July. “Not all of Magma came from our mum passing, but it affected us, of course, deeply,” says Joe. “It was such a huge deal in our hearts and minds, spiritually. It happened exactly as we were writing songs, so how to avoid that? It’s impossible. It’s all over the album.”

“Our mum always said: ‘Death is part of life. You have to accept that,'” Mario says. “Talking about death was not a problem. When we were kids, she always thought it could be an interesting discussion. You’re born and you’ll die; that’s the circle of life. So, as a child, I really didn’t understand why everyone would cry and wear black clothes when someone died.”

As a result, Magma isn’t a dirge, but an inquisition into what is beyond death. The opening rocker, The Shooting Star, gives Patricia directions to the afterlife through the constellations: “Between the bear and the scorpion, you’re getting close.” The title track mentions reincarnation and climax; Low Lands begs for her knowledge of what is beyond the grave.

The insightful post-metal earned Gojira two Grammy nominations and they supported their idols Metallica on the accompanying tour. However, as proud as Gojira are of the album that brought such success, Fortitude is an intentional reversal. It maintains Magma’s alluring simplicity, but swaps to a motivational headspace. “Magma was intimate, an inside thing, whereas Fortitude is an outside thing: a more outgoing, punchy and political thing,” says Joe.

It’s also an ode to the Duplantiers’ artistic childhoods, exploring more than just the trauma of the climate crisis. Born for One Thing references Thai and Tibetan philosophy; the uplifting refrain of The Chant is as folk as it is metal; and The Trails is prowling prog-pop – something that could have been played on the radio back home. “We had a great time with our parents listening to the Beatles and Pink Floyd,” says Mario. “I always wanted to add a few elements of that.”

Representing metal at its eclectic, morally astute best, Fortitude deserves to turn Gojira into megastars, yet the band eye their future with excitement and cynicism. “I want us to be relevant for a long time, but at the same time I really don’t,” Joe says. “We’re talking about big issues here. They need to be solved.”

Fortitude is out now on Roadrunner Records.