The pandemic has not been the only crisis we’ve been wading through over the past 12 months: 2020 was a banner year in much of Britain for sewage spills. Last July a Guardian investigation revealed that raw sewage had been pumped into English rivers via storm overflows more than 200,000 times in 2019. In November, Surfers Against Sewage (SAS) published data showing that untreated wastewater was discharged on to English and Welsh beaches on 2,900 occasions in a year.

Then last month, under mounting pressure, the Environment Agency published, for the first time, full data on raw sewage discharges last year, showing a 37% year-on-year increase: 3.1m hours of human effluent flows, pumped via storm drains into English waters in some 400,000 occasions.

Not since SAS was founded in 1990 – when untreated wastewater piped directly into the sea and flowing back on to British shores caused a scandal – has so much untreated faeces spread so far. Hugo Tagholm, SAS’s chief executive, says the country is facing “a second wave of sewage pollution”.

The prevalence of raw sewage in British waters is not only about the horror of swimming amid human waste but about the health and environmental threats of microplastics (especially from laundry water), endocrine disruptors (chemicals that interfere with hormones found in plastics, detergents and cosmetics), phosphorus (which causes algae blooms), antibiotic-resistant bacteria and even Covid-19 – all spread through wastewater.

All overflows reach the same place. “All of our waterways are connected,” says Tagholm. “It’s one cycle: what goes into our rivers ends up in our ocean.”

The country is belatedly waking up to the crisis. New ideas are being proposed – sustainable drainage, use of artificial intelligence (AI), even doing away with sewers altogether. Meanwhile, communities and increasing numbers of wild swimmers, surfers and paddle boarders are piling on pressure, because the solutions do not only involve water companies and sewers but the fabric of our cities, towns and villages, as well as farms taking responsibility for their polluting runoff.

“Despite the progress that investment has made,” says Tagholm, “we still see thousands of sewage pollution events each year emanating from the combined sewer overflow network on our coastline, and particularly in our rivers.”

In short, Britain literally oozes sewage. How did it come to this? Most Britons don’t think about what happens when they flush their toilets. It probably involves a “combined sewer network”, fed by rainwater – including road and land runoff – and buildings’ waste drains. After the 1990 sewage crisis, the urban wastewater directive stipulated that water companies must treat sewage rather than dump it in the sea. So, on a good day, wastewater flows to the sewage treatment works, where it undergoes filtering, dewatering, processing and recycling.

But good days are increasingly rare. Previously, only freak storms would fill the system to the point that the toxic soup would spill out into waterways (to avoid the even grislier prospect of it spouting back up our drains). Now, however, both the number of houses and the frequency of storms have increased. The system is so far over-capacity that in some areas drizzle can make it overflow – and blockages and fatbergs can cause overflows even when it’s not raining.

“We’ve got 15,000 storm overflows,” says Keith Davis, the Environment Agency’s water-quality regulatory development manager, “and the majority are on the combined sewer network, with about 100,000km of combined sewer in England alone.”

That’s a lot of sewer to manage at the best of times, which these are not, he says. “We’ve got climate change, population growth and urban creep,” meaning the loss of permeable surfaces to absorb rain. “A small-scale example is someone paving over their front garden to provide parking. If a number of people do it, it will increase the runoff.”

In London, sewage overflowing into the Thames has been an urgent problem for many years, with about 39m tonnes spewing into the river each year. The GBP4.2bn Tideway super sewer, under construction since 2016, aims to tackle this. It has been built to last 150 years, but what happens after that? Even bigger and deeper concrete structures? And what about the rest of the country?

James Harrison, head of wastewater assets for Yorkshire Water, thinks hard engineering alone is not a feasible solution. “You can’t typically invest your way out of it by enlarging sewers, pouring lots of concrete and having big tanks. That costs an awful lot of money, and it contains a lot of embedded carbon.”

Davis has reached a similar conclusion. Vast tanks, such as those under the promenades in Blackpool and Brighton, have been built to hold excess stormwater, so it can be fed back into sewers once the water levels in the sewers drop. But he argues this “grey infrastructure approach” is not a long-term solution.

“We’re looking at a move towards more green infrastructure, that slows surface water or prevents it getting into the sewers,” Davis says.

A key example of green infrastructure solutions are sustainable drainage systems, known as SuDS. These allow the environment to absorb, slow and divert water. They use wetlands, ponds and green ditches called swales, as well as green roofs, rainwater-harvesting systems and replacing nonabsorbent surfaces with porous asphalt or gravel.

Most prominently, SuDS have been used to stunning effect in China, where flood-prone cities, such as Wuhan, have come to be known as “sponge cities“, full of beautiful, biodiverse parkland that holds on to water. Other examples include Malmo in Sweden, which blazed a trail for “blue-green cities” at the turn of the century after introducing a series of trenches, ponds and wetlands to absorb up to 90% of its stormwater. Davis says the Environment Agency is also looking at “Copenhagen, as well as some of the American and Canadian examples – Seattle and Vancouver – where they’re trying these different approaches”.

Some SuDS have already been retrofitted in the UK. The combined sewer system in the seaside town of Llanelli in south Wales regularly polluted its shellfish-rich waters. But over the past decade it has had a GBP15m blue-green makeover, costing a quarter of the estimated amount needed for building a bigger sewer.

As part of the Llanelli project, a swale was constructed to take runoff from the road network. A swale, says wetland engineer and chair of the Constructed Wetland Association, Geoff Sweaney, is a shallow, grassy ditch that slows the flow of water. “The particles of oil and other road pollutants in road runoff will get filtered, rather than running straight into drains or rivers,” he says. So not only do swales help stop sewers from overflowing, they also keep them cleaner. Although, Sweaney notes, “We still have a lot to learn – there is some incredibly complex stuff happening with the chemistry of wetland environments.”

The SuDS concept has been around since the 1990s. But until now, says Sweaney, “adoption, and the enforcement of the legal requirement to include SuDS in all new developments, has been very weak”.

One issue is that wetlands require maintenance. “If you imagine a pond or wetland in the middle of a city,” says Sweaney, “if no one’s looking after it, it just ends up getting full of shopping trolleys. If it falls on the local authority – and local authorities don’t have the money – then that’s a bit of a disincentive for them.”

However, by working with local government, industry, environmental and community organisations, they can work. Sweaney is developing a SuDS project near Fleetwood in Lancashire for the Wyre Rivers Trust.

“There’s a brook that has basically become a drain. We’re creating a new wetland floodplain alongside the stream and diverting surface water drains from the housing estate through the wetlands.” The landscape architecture firm involved is designing a wetland walk with boardwalks; the local water company, United Utilities, is “on side”.

However, SuDS and concrete tanks are not the only weapons in the anti-sewage spill arsenal. Fatbergs and other blockages can trigger sewage pollution events, so having a better idea of what’s going on underground is essential. Harrison says Yorkshire Water is working with Siemens on a pilot “fuzzy logic” network around Ilkley, which uses real-time rainfall data, AI and sensors to better predict blockages. So far, the project has been able to predict nine out of 10 blockages – three times more accurate than existing statistical modelling – while reducing false alarms by half.

After months of campaigning, Ilkley is celebrating becoming England’s first designated inland bathing site. This has greatly sped up plans to improve how it deal with its sewage. “Putting technology and instrumentation out in the network could help us make better operational decisions,” says Harrison. “Holding flow back up in the network, and then introducing it in a more gradual way, and responding where issues may be developing. Until now, it’s been quite a manual approach.”

A more radical solution to the sewage crisis is to do away with sewers altogether. Peter Cruddas, senior lecturer in water and environmental engineering at Portsmouth University, started researching flushless toilets for developing countries, and is now considering how these could apply to the rest of the world. He does not, however, envisage “getting someone on the 20th floor of a high-rise in the middle of Birmingham to deal with their own waste to create compost”.

Instead, Cruddas has identified three designs that could complement one other, depending on local circumstances. For people with gardens, waste would be sanitised and deodorised within the toilet unit, “and the end-product would be made available directly to the user: this would likely involve heat-treatment as the best way to stabilise and dewater the waste as much as possible”. The sanitised waste could then be added to compost heaps.

Another concept is to use a municipal collection system, says Cruddas, “where the product is combined with garden or food waste collections, for minimum disruption to existing infrastructure. You would be replacing a costly and environmentally damaging water-based system with a system that’s already in place.”

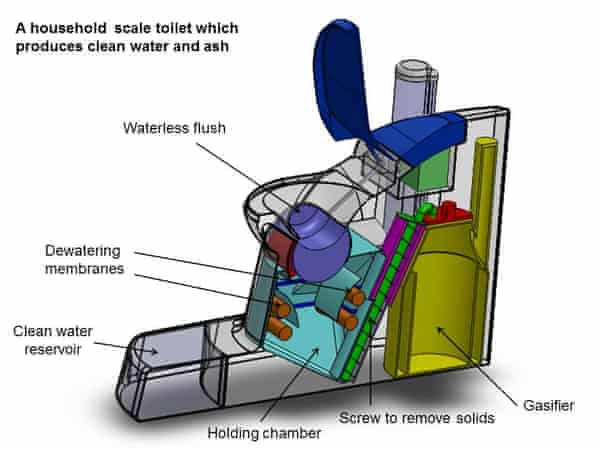

A third approach, the most “hands-off, although also the most wasteful”, says Cruddas, would be “to just destroy the waste in the toilet”, resulting in “very small quantities of ash that could be disposed of in a normal black bin, or used on gardens if desired”.

This is the idea behind a project Cruddas previously worked on: the nano-membrane toilet, developed by Cranfield University. Liquids undergo evaporation, killing many pathogens in the process, and can then be used for washing or irrigation, while solids are burned, producing enough energy to power the unit. While this approach fails to “recover some of the useful resources in human waste”, Cruddas says, “at least you wouldn’t be wasting millions of litres of water every day to flush toilets, while damaging the environment through the stormwater outfalls”.

Cruddas is seeking funding to develop these design ideas, and present them to industry, as well as political and regulatory bodies. Some agencies seem aware that big changes are needed. For example, the net zero routemap of Water UK, the water companies’ trade body, says SuDS “will cut the carbon emissions associated with unnecessary treatment of surface water at sewage works”. It adds that they boost biodiversity, too, and reed beds’ cleaning abilities are impressive.

Reed beds are already used to bring water from some sewage works up to a safe standard for release into rivers, and can even clean wastewater from chemical plants. They can process raw sewage naturally, too, as a passive alternative to sewage works – a technique commonly used across rural France, and now being trialled in the UK.

All this is possible, but as Callum Clench, of the International Water Resources Association, points out: “The EU set river water-quality standards – and the UK was regularly fined for failing to meet these standards.” Now Britain is no longer in the EU, he says it is vital that communities keep up pressure on the government to ensure the UK does not lower its standards.

It also falls on all of us to plan for our local land. We can apply for natural swimming spots to become designated bathing areas, requiring real-time pollution reports. We can monitor the health of rivers. We can avoid paving, artificial turf and asphalt. We can harvest roof runoff in water butts. We can be strict about not putting oil and wet wipes down drains.

“We’ve got to look at this in big blocks of time,” says Tagholm. “In 2030, we want to look back on a decade where we really made a difference to our rivers and coastline.” The era of flush and forget may have finally had its day.