There are now three recognised species of elephant – the Asian elephant, the African savanna elephant and the African forest elephant.

All three are recognised as threatened with extinction after an important revision to the “red list”, where the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) compiles a regularly updated assessment of at-risk plants and animals.

For many elephant experts and poachers alike, the split into two species of African elephant has long been obvious. Researchers proved the difference more than 10 years ago. Now conservation is catching up, with the first red list assessment of them as two separate species.

“They’re big and grey, so easy to think that they’re very similar,” says Dr Kathleen Gobush, an elephant specialist who led a team of six IUCN assessors for the new classifications. “But once you spend time with them, a lot of differences are noticeable.”

The African forest elephant

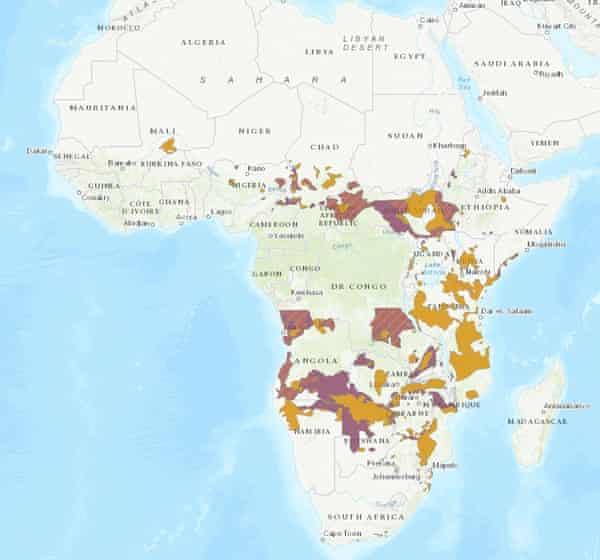

Mainly found in the Congo basin in west Africa, it lives in dense tropical rainforest and is the more threatened of Africa’s two elephant species. They are voracious fruit eaters – vital ecosystem engineers that help maintain the health of the rainforests.

“Their scientific name, Loxodonta cyclotis, references their smaller, rounded ears. Their tusks point downwards, occasionally reaching the ground in older males, and their body is higher over the back legs,” says Prof Lee White, minister of water, forests, oceans, environment and climate change in Gabon, home to the largest remaining population of forest elephants.

The mammals live in smaller family groups and have longer gestation periods than their savanna relatives, meaning that populations targeted by illegal hunting are often slow to recover. Their ivory is pinkish and denser, and often preferred by poachers, who have helped drive the species nearer to extinction.

Few standalone studies of the forest elephant exist as they have often been lumped in with the savanna, but a 2013 paper by University of Stirling biologist Dr Fiona Maisels found that its population is below 10% of its potential size and occupies less than a quarter of its potential range.

Genetic analysis indicates that the African forest elephant could have been a separate species for millions of years. Dr Alfred Roca, a population genetic specialist at the University of Illinois who has published several leading studies on elephants, said the mammoth, the savanna elephant, the forest elephant and the Asian elephant probably separated at the same time, about 5-6 million years ago.

“During the ice ages, Africa became much drier and the forest retreated. I think each of those [species] probably had an isolated population. That may account for the high diversity, that you had separate populations that eventually came together,” says Roca.

The African savanna elephant

The biggest terrestrial animal on Earth lives in larger familial groups in grasslands and deserts, roaming huge distances in central, eastern and southern Africa.

Savanna elephants have large ears that are the shape of Africa and allow them to cool their bodies more easily, and longer front legs, unlike their forest elephant relatives.

“Savanna elephants have a big presence. When you’re around them, all your attention is there. They can be very charismatic or comical, a little bit frightening at moments. It’s a really amazing feeling. The only other time I felt like that would be when I’ve been around whales,” says Gobush.

“Because savanna elephants are more conspicuous, they’re more of a tourist attraction because you can see them and they’re not hiding in the dense forest. They dominate the conversation around African elephants.”

Although the savanna elephant is classified as endangered by the IUCN, meaning it is threatened with extinction, subpopulations are thriving in parts of Africa, most notably in the Kavango-Zambezi transfrontier conservation area between Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

But experts warn that savanna elephants are likely to be at risk from habitat loss and human-wildlife conflict, which is increasingly being borne out in statistics on elephant killings in Africa.

“African savanna elephants are occupying about 15% of what they used to occupy. Unless we change our planning, then we will keep seeing conflict,” says Dr Ben Okita-Ouma, co-chair of the IUCN elephant group and head of monitoring for Save the Elephants.