When I was growing up, one of my parents’ favourite albums was a live recording of a Pete Seeger concert called We Shall Overcome. On it was his rendition of a Bob Dylan song called Who Killed Davey Moore. Pete’s voice imploring an answer to that question would ring out from the record player in the living room and across the house.

The song explores the question of who bore responsibility for the death of an African American boxer who was killed in the ring when he was just 30 years old. Each verse begins with the refrain, “Who killed Davey Moore?” In the verse that follows, some group or individual associated with his life and death – the coach, the crowd, the manager, the gambling man, the boxing writer, the other fighter – gives their answer. Each, in turn, responds “Not I”, and explains that they cannot rightfully be accused of killing Davey Moore. They were just doing what it is that they do: going to the fight, organising the fight, writing about the fight, throwing the punches, and so on. And, of course, they are each telling the truth. Or a truth of sorts.

Even to the child I was then, the song conveyed the miserable inadequacy of reducing responsibility to something uniquely borne by individuals who malevolently commit bad actions. The repetitive beat of justification and exculpation left no doubt in that little girl that even those who could swear that they had not committed the actual act of killing, and certainly had no intention to kill, had their hands deep in his death. This was no tragedy, as if he had been inexplicably struck down by the fates, like a figure who falls on the stage in a Sophocles play. They all killed Davey Moore.

Who killed the 3 billion animals we estimate died as a result of Australia’s devastating bushfires of 2019-20? What about the trees, the grasses, the insects, the microbes, the fungi? What about the people? What about our faith in the future? What about summertime? Their deaths, and the threats they face in the future, are no tragedy. We know what killed them, and we know what is threatening the lives of all of us who remain. But our knowing lacks language, lacks law, lacks a path to action.

This is not the first time we have stood in the face of crimes we could not name. At the end of the second world war, as the full extent of the devastation of the Holocaust became apparent, Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jew whose entire family had been killed, pulled himself from a grief we can barely contemplate to try to find ways to prevent the killing he had witnessed from ever happening again. In facing that gargantuan task, he realised that he could not even get started as long as there was no name for the distinctive crime that had been committed: the murder of a people. So he set as his first goal giving a name to the crime, and then to convince the world to use this name and thereby come to recognise it as a crime. He achieved both. Today the term genocide is part of our lingua franca, and although we have not yet learned how to prevent genocide, few would argue that it is anything less than a scourge on the earth. Today, no one calls genocide a tragedy. No one says, it’s unspeakably terrible, but after all, it’s no one’s fault.

Lemkin’s greatest aspiration, and one he barely had a chance to commence before he died, was to develop the laws, build the institutions and create the understandings that would have the world not only name and condemn genocide but actually go about ensuring that it did not happen. Among the many reasons that might explain our continued failure to realise his aspiration is the Davey Moore problem. True, the specific murders of the individuals who belong to the murdered people can be traced to specific killers, but the roots of genocide, the causes that perpetuate it through history, burrow far deeper into our politics, our economics, our cultures, and our ways of making sense of who we, and who others are.

What then might we make of this killing of our age? What word might we give to it? I have written of the death of animals, of trees, of ecosystems and of summertime. Others have written and spoken of the deaths of animals and places they treasure, of people they know and have loved, of oceanscapes, of insects, of living beings we cannot see but know are disappearing, of entire species; the death of their sense of being at peace in the world. In the future they may be writing of the death of civilisations.

Already, as parts of the planet become too hot for humans to continue to live there, or too volatile for them to live safely, civilisations woven from millennia of connection to place are being mourned by people who carry away stories of worlds being left behind. The ubiquity of the climate catastrophes unfolding – not only here, where I felt the fire, but across the planet – can perhaps give us some inkling of how deep we are all in this. The killing has no boundaries. Everything is within its sights. Perhaps the term could be omnicide. The killing of all. Not just all humans, as if humans were the only beings that could be murdered. All beings.

What would it take for us to stop this killing? How do we even begin to wrap our heads around its enormity? How do we trace the complex roots of responsibility into all the places where they are dug deep into our politics, into our economics, into the ways we understand ourselves and everyone and everything else with whom we share this earth? Can we learn to tell new, far-reaching stories about responsibility?

And if we can learn to tell these types of complex stories, how do we go about wresting our lives and ways of life back from those pathological practices and malignant institutions? How do we learn to understand ourselves and everyone else, human and other-than-human, in ways that will help us to extricate ourselves and those who will come after us from omnicidal ways of being human? How do we attach ourselves to stories that have the power to woo us away from the spells of progress and the logics of exploitation and violence that have legitimated the killing?

Shining an accusatory light on an evil killer is both easy and relatively satisfying. It drives the script of the tales in which we absorb ourselves as we retreat from a world become too much. Far more unnerving is to recognise that the killing is the secretion of this human world just doing what it is that it does. Day in day out. This killing is not an event but a condition.

Pete Seeger sang for the 60s in the hope that the people who heard him might step out from passivity and take on the violence and injustice infecting their world. If we were now to sing, “Who killed everything?” would we fill the verses with a new version of “Not I, not I, not I”?

Or could we now, while we still can, sing and then answer, “I, I, I”?

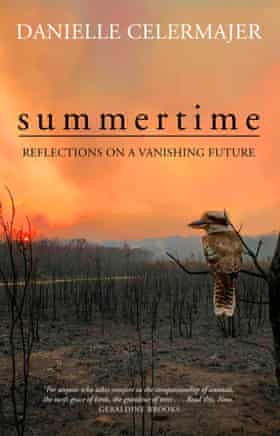

o This is an edited extract from Summertime: Reflections on a Vanishing Future by Danielle Celermajer (Penguin Random House, $24.99)