Like many people, 81-year-old Jon Sanders gets up and makes himself a coffee each morning. Instant, two sugars, milk. It’s a conventional start for a man who lives anything but an ordinary life.

Sanders this week became the oldest person to sail single-handedly around the world – a voyage to raise awareness about plastic pollution and one plagued by coronavirus at every port.

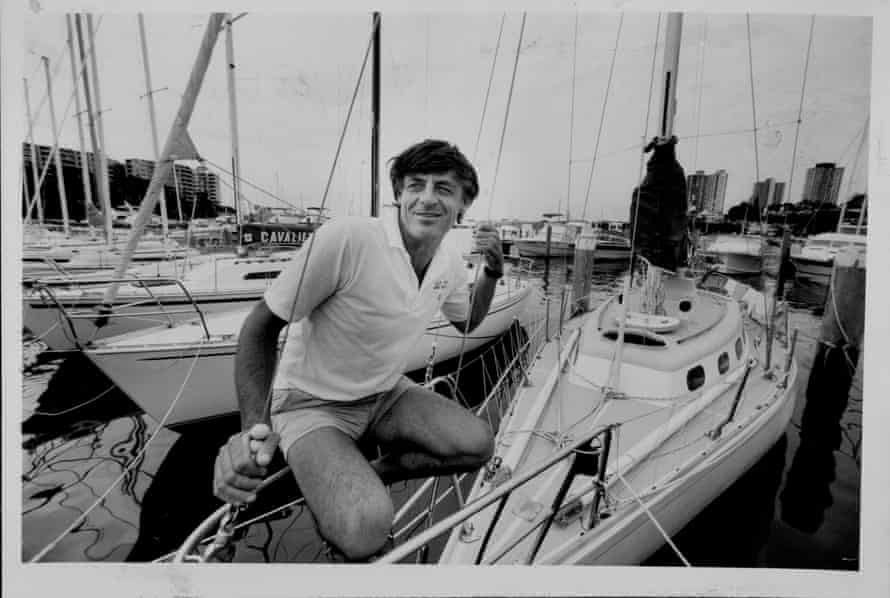

On 31 January, nursing cracked ribs from a night strapped into his bunk after giant waves engulfed his boat off Tahiti, the octogenarian sailed his old 39-foot yacht, the Perie Banou II, into Western Australia’s Fremantle Harbour, notching up his 11th solo navigation around the globe.

It was a wild ride for Sanders from start to finish.

A succession of Covid lockdowns blew his eight-month itinerary into a demanding 15-month voyage. Worse still, the delays meant that instead of his plan to follow favourable currents and helpful winds, he was hauled into the path of massive storms with mountainous waves.

For someone who has accomplished such gruelling physical and mental feats of endurance, he is surprisingly down-to-earth and refreshingly humble.

“I’m supposed to be a weirdo, but I’m not,” Sanders jokes. “I’m boring.”

Despite the claim, there are quirks that hint at his unique life.

With piercing blue eyes crinkled by the sun and tough, tanned skin, he looks as strong as someone half his age (cracked ribs notwithstanding). He eats a spartan diet – never any breakfast, and just coffee most days for lunch. When at sea, dinner is typically a can of vegetables, powdered potatoes or maybe some soup.

Sanders has a phone, but it is without charge and stashed away. He has no house, partner, or pets, and to find him one must chance a stop by his bright yellow boat. Despite his regular months-long periods of solitude, he insists he never gets lonely.

“It doesn’t bother me being alone at sea,” Sanders says. “I like having a crew, but I don’t care if I’m by myself.”

A lifetime of extreme sailing has quietly garnered Sanders 12 world records, honours including an OBE from the Queen and an Order of Australia, and a road bearing his name in his hometown of Perth.

In 1982, Sanders became the first person ever to double-circumnavigate the globe alone. A few years later, he become the first person to sail solo and continuously three times around the world in 1988, travelling more than 71,000 nautical miles – a feat described by Guinness World Records as “longest period alone at sea during a continuous voyage: 419 days: 22 hours: 10 minutes”.

Nowhere is off limits for Sanders, who battled icebergs, freezing winds and huge waves during a solo double circumnavigation of the Antarctic in 1981-82. While many have followed, he was the first.

Steadfastly modest, Sanders says he doesn’t set records to achieve fame.

“Most people would think I do it to be the first person to do something, but I think it was more about convincing myself that I could do it, because I thought I could. Then you end up with a record.”

A man on an environmental mission

Sanders’ first circumnavigation in 1970 may have been purely about rising to the challenge, but after decades of watching plastic debris accumulate on the seas, the old sailor decided to try a fresh tack.

“As someone who has spent more than 60 years traversing and enjoying the world’s oceans, I could not sit idly by and watch that same environment be choked to death with plastic waste,” Sanders says.

For an hour each day during his latest voyage, Sanders filtered 115L of seawater through a specially designed pump using a hole drilled in the hull of his boat.

A hole below the waterline is risky. But it allowed Sanders to collect hundreds of water samples, in all weathers, from across the Indian, Atlantic, Pacific and Southern Oceans.

Part-sponsored by mining magnate Andrew Forrest’s philanthropic Minderoo Foundation, the samples will help researchers compile a database of microplastic concentrations in shallow ocean waters, and track future changes.

The Curtin University environmental toxicologist Dr Alan Scarlett has found microplastics, smaller than a grain of sand, in virtually every one of Sanders’ samples he has studied so far.

“We found all the common plastics that you would find in a household,” Scarlett says.

Two samples taken 600km off the coast of Brazil contained three times more plastic than those from the Indian Ocean, Scarlett found.

He says that while Sanders’ samples are “just a snapshot”, they align with other findings showing plastic is present all over the world, even in Arctic and Antarctic waters.

A life all at sea

Born to a writer mother and university professor father, Sanders started sailing with his brother Colin at 12 and spent his winters shearing sheep before embarking on a yachtsman career.

Over the decades he has taught his body to sleep in 20-minute bursts when navigating at night through busy shipping lanes.

Despite what he says is an “overcautious” approach, he has accidentally run into whales, collided with rogue trawlers that have turned off their radar to evade scrutiny, and survived being rolled in huge swell.

Sanders insists old boats are better than new. He has used the same Sparkman and Stephens yacht since 1971.

“Modern boats are built different. They are wider, higher and the bottom is flatter,” Sanders says.

“The modern boats bang every single wave. I wouldn’t be able to do some of the things I’ve done in the past with a modern boat.

“The older boat is like putting a cork in a Coca-Cola bottle, because it has a lead weight on the bottom it comes up quickly if something bad happens.”

While roiling through waves may be perilous, Sanders saw catching coronavirus as his biggest threat this trip.

“I’m a dead duck if I get Covid at my age,” he says.

There was no coronavirus pandemic when Sanders set off from Fremantle Port on 3 November 2019. By the time he reached the Caribbean in March 2020, the contagion was widespread.

Lockdown life was the world’s new normal.

With Sanders stuck in port on the southern Caribbean island of Saint Maarten, his voyage manager, political geographer Dr Stephen Davis, had no choice but to tear up a carefully planned itinerary and begin working to get the sails back in motion before cyclone season arrived.

But Sanders hit another lockdown in Panama, delaying him by four months. After yet more holdups in Tahiti and Sydney, he arrived home the very week that Perth was locking down after 10 virus-free months.

“This voyage had lots of challenges in the sea conditions [and] the sampling of plastics, but none were bigger than the challenges of managing the quarantine requirements of the Covid lockdowns,” Davis says.

“Negotiating immigration authorities in each successive port was torturous, convoluted, and a different challenge each time.”

But sailing during a global pandemic did offer Sanders one silver lining: no cruise ships.

“In the Caribbean in other years, it’s been cluttered with cruise liners and they leave at night and go around in circles. That doesn’t make it easy for a lone yachtsman to cross the Caribbean Sea,” Sanders says.

Becalmed for the moment in his home port and finding lockdown isolation not so different from his ordinary extraordinary life, Sanders says he can’t imagine another epic ocean adventure.

“But who knows,” he shrugs. “You can never say never.”