I was on the Eurostar, somewhere between St Pancras and Paris, when a senior member of the Guardian team called and suggested that it might be a good idea for me to turn around at Gare du Nord and return to London.

It was 3 March 2020. This was not the plan. The plan had been to go to the Chanel show and report for the news pages. Instead, it was the beginning of all plans – work and otherwise – disintegrating.

2020 was a terrible year for the world, and a head-spinning one for fashion. Almost everything that could have unravelled did, from brands reneging on orders and shamefully leaving garment workers unpaid, to the cancellation of Hollywood red carpet events, to the nixing of fashion shows in New York, London, Milan and Paris.

At first, everything the Guardian’s fashion desk did had to change. Our news coverage could no longer echo the rhythms of the fashion year; our stylists could not produce photoshoots, for social distancing reasons. The practical style advice we had planned – based on a summer of holidays and weddings – was, of course, scrapped. In those early, doom-scrolling days, the only commodities of interest were face masks, hand sanitiser and loo rolls.

In truth, it was bewildering – until it dawned on us that the fashion industry being turned upside-down was, itself, a fascinating story.

We pivoted. And we reported on designers pivoting, too: on British designers forming the Emergency Designer Network to make PPE; on fashion magazines featuring NHS workers, not celebrities, on their covers. We covered the moment when face masks became normalised and, inevitably, adopted by fashion. We reported on the weird new British high street – from trousers being quarantined to the fall of the once-mighty Topshop.

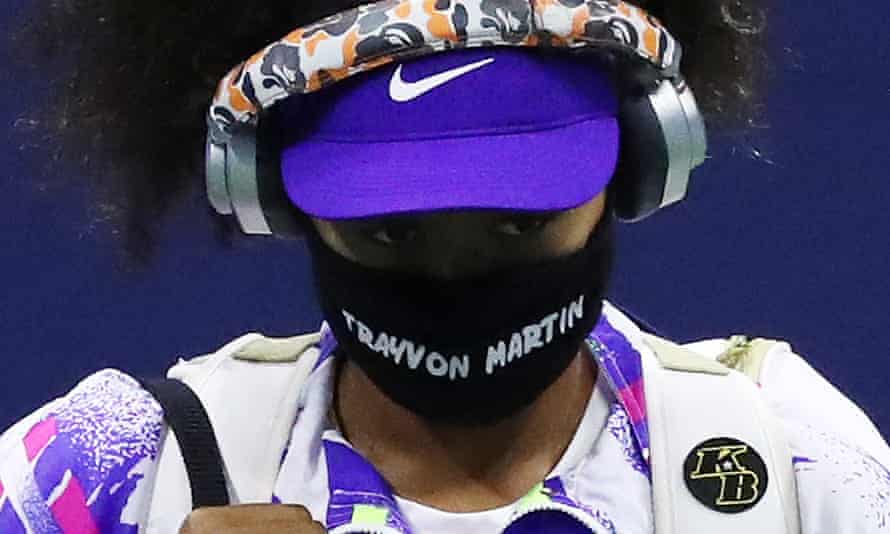

Fabric was caught in the crosshairs of an unexpected number of major international news stories in 2020. As protests swelled in the US following the police killing of George Floyd, we reported on the ways in which clothing was weaponised, including Black Lives Matter slogans being banned by employers. We reported on Fred Perry withdrawing its polo shirt after it was adopted by the far-right Proud Boys group and the “Vote”-slogan merch produced and worn by Michelle Obama, among others, in an effort to mobilise young voters.

We reported on the items selling, despite everything: in April, sweatpants were up (you’re probably wearing a pair now); in October, it was all about the kind of strange shoes you might wear to take out the bins, such as Crocs, which seemed to say something profound about the collective psyche. Some of the most interesting aspects of fashion came to the fore as people searched for soft, cocooning duvet coats to envelop them on winter walks, or bought detachable “Zoom” collars – surely the most 2020 of accessories – in order to present their best face as the world crumbled, and with all communications taking place through front-facing cameras.

The items that have been put on furlough – bras, high-heeled shoes, hard waistbands – told a story too, as did our coverage of self-soothing lifestyle trends, from decluttering to scented candles to the improbable rise of “tablescaping”.

One unexpected pleasure to be found in the absence of real-life people watching was the rise of the armchair fashion critic. During lockdown, analysis of style on TV has reached an all-time high – and we have been binge-watching too, writing about Marianne’s summer style in Normal People, the controversial Undoing coat, unpicking the weirdly prescient best-foot-forward dressing of Schitt’s Creek and analysing the historical accuracy of the breasts in Bridgerton. The popularity of these pieces seem to speak to a collective desire to enjoy aesthetics, and to analyse the meaning of a cuff, hem or cut, even when we are permanently in our pyjamas.

Some normality has returned. Our stylists have been shooting celebrities and fashion stories again, when social distancing guidelines allow, and even got the All Ages band back together for Christmas. But mainly, as with everyone else fortunate enough to work safely from home, our worlds have become very small. We have found stories by speaking to contacts on the phone, monitoring social media trends, and watching audience-free catwalk presentations and digital shows which have mainly replaced the standard show calendar. Only our intrepid critic Jess Cartner-Morley attended a handful of socially distanced Milan and London fashion week shows last September, where mask-clad designers held one-to-one appointments.

With concerns about sustainability at an all-time high, it has been encouraging to see so many designers discussing the scaled-back ways in which they would like to rebuild the industry after this crisis. It looks as though the fashion show circus – which all agreed was sprawling out of control – will be pared back, though it seems unlikely that digital shows will be a permanent or blanket answer. The human side of a fashion show – the ability to read the room, see which looks inspire gasps from the fashion students standing at the back, or spot the beginnings of a trend in the frontrow prevalence of a startling new haircut – has been sorely lacking.

That said, this pause – not to mention all our fresh concerns about economic crisis – has given us the opportunity to double down on our own “slow fashion” approach to style, whether recommending ways to mend clothing, or to shop second-hand first, or finding fresh ways to style our existing clothes, or offering carefully-chosen shopping tips, such as clothes to keep you warm when socialising outside as advised by outdoor workers, and the best places to find chic, ethically-made underwear. We have also had the opportunity to report on a few heartening developments – from the rise of DIY fashion, such as tie-dye and crochet, to the second-hand clothing boom in the pandemic – which suggest that a more mindful approach to style, and a slowing down of the late capitalist attitude towards consumerism in general, could be on the horizon.

Clearly, the world is in existential crisis, and the fashion industry with it. There seems a genuine chance, however, that fashion could rebuild in a slower, more considered way, leaving it looking better than it has for a long time. This period of change has also been rich from a journalistic point of view, even when it has been personally terrifying. That’s something I would never have imagined, when my heart sank, as the world as we knew it started spinning away, that 3 March on Eurostar.