Since the idea of rewilding took hold, it has generally been seen as a rural pursuit involving withdrawal from farmland so that animals and vegetation can restore their own ecology.

At its most herbivorous, it includes allowing hedgerows or scrub to flourish unchecked. At its most primal, it involves deliberately releasing animals such as beavers or wolves in the belief that the re-entry of a single alpha species brings with it a cascade of ecological benefits.

Either way, rewilding has come to be associated with big acreages, whether that be at Knepp Park in Sussex or at the 18,000-acre Glenfeshie estate in the Cairngorms. The perception is that it is expensive, far away and often inaccessible. It certainly isn’t something that just anyone can do.

But what if the wildest places of all were right under our feet? In the forgotten spaces in our cities, rewilding has always happened naturally, , land falling under stone and resurging again, concrete lids flipped off before submerging once more. In the margins and the demilitarised zones, the abandoned embankments, the bits we don’t want or the lands already contaminated beyond human tolerance, ecology is thriving.

In some places – such as the land around the abandoned Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine – plant and insect life has adapted to the extreme conditions: boars have moved in, there is a new radiation-munching fungus and, in the thin strip of no-man’s land between the borders of North and South Korea, leopards and Asiatic black bears have been spotted. In the past century, Greenham Common in Berkshire has transformed from open heathland grazing to the home of US Trident missiles to an SSSI nature reserve with a weedy runway.

In Scotland, the 40-mile strip between Glasgow and Edinburgh has always been mined, for not just coal, but stone, gravel, lead and even gold. After centuries of hard pickings, parts of Lanarkshire and Ayrshire have an upended appearance. What was underground is now on top and what was above has gone below, with buildings and bridges slumped over old drift mines and razor-lined spoil heaps terraced by extraction tracks. Wildfowl nest on lochs made from old coal holes and an orchid called Young’s helleborine, discovered in 1975, favours only the best iron ore.

The Ardeer peninsula in Ayrshire is home to the unusually bracing combination of a nudist beach and an explosives factory once owned and operated by the Alfred Nobel Company. Parts of the site are still in use, but most of the 330-acre site was long ago abandoned. Along the cracks in the old pipelines and through the decaying buildings, it would be quicker to list the native plants that are no longer there than those that are.

In theory, industry and mining companies are supposed to follow restoration plans for abandoned sites, but in practice they often plead poverty. Besides, ecologists sometimes find themselves ensnared in a paradox. Public feeling is that big business should be obliged to make good what it has taken, but human attempts to restore land are often amateurish. Planting a few conifers and flinging around a mix of wildflowers may be a quick fix, but sometimes it appears that the best thing to do is nothing.

The M74 motorway runs up the front of Scotland past new windfarms and second world war PoW camps. Not far from Broken Cross, Europe’s largest opencast coal mine, there’s Castle Dangerous. In 1913 the 13th Earl of Home tried to lift local unemployment at Douglas by allowing mining nearby. The mining unseated the castle, it was demolished, and the flooded workings (known locally as the Black Hole) are now so patterned with commuting birdlife that it resembles an avian Heathrow.

Further up the motorway, near Port Glasgow, the old timber ponds attract birds of a seaborne kind. The ponds are shallow estuarine mudflats divided by ancient wooden stakes (or stabs) and were once used to grade and store logs for shipbuilding. It is an atmospheric place, the stabs shrouded in black weed like cartoon ghouls while beyond them the lights of Dunbarton shine over the water. Poking around in the mud and sunken tyres I hear a curlew for the first time this year, its song for an instant rhyming with an ambulance siren.

On the other side of the Clyde, between the Erskine Bridge and the old John Brown shipyard, lies what used to be the Beardmore naval construction works in Dalmuir. In the early 20th century it produced munitions, planes, submarines and warships before being converted into a fuel-supply depot and then being gradually abandoned.

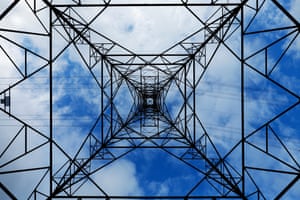

Now a cycle path runs through it, but otherwise there is nothing new here except nature: golden leaves of birch springing from the concrete jetty, hawkweed drifting Ophelia-like in the drowned oil storage tanks, wrens nesting in the rusted embankments, mallards cackling from the blackthorn scrub. “Have you seen the deer?” asks a dog walker. There are two, apparently – one red, one roe, both favouring the grazing just beneath the giant electricity pylon.

Dalmuir is beautiful, dangerous – and almost certainly contaminated. Like many of the other sites, it has always been used by more than just squirrels and crows. Since industry retreated it has been a flytip, a heroin shooting gallery and probably a place to dispose of worse things than just old mattresses.

Halflands like these can be among the most joyous and optimistic places on earth, but they can also carry with them a polluting sense of menace. Finding them means that you may end up meandering across an indeterminate line between a walk in the park and full-scale urban exploration; you explore at your own risk. Some places encourage public interest and others, despite Scotland’s differing access laws, discourage it.

They also have a habit of vanishing. Brownfield sites tend to be classified as wasteland, and with the pressure on housing, they are first in line for redevelopment. Ardeer is intended for “regeneration” and Dalmuir will shortly be dug up to make way for the Scottish Marine Technology Park, a deepwater ship hoist and a new small-vessel fabrication yard. Malin Group, which owns the site, says it will create 600 short-term jobs and give a multimillion-pound boost to the local economy, which it claims is “sure to bring back to life this area of the river”.