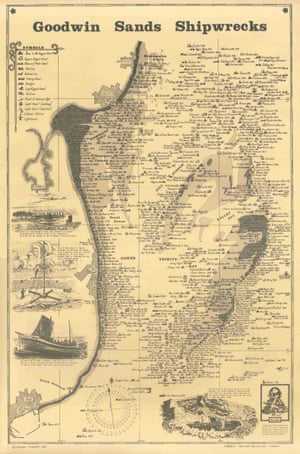

Six miles off the coast of Deal, in Kent, lies Goodwin Sands, a 10-mile sandbank known as the “ship swallower”. Seals bask there at low tide, belying its reputation as one of the most treacherous spots in the Channel and a graveyard for centuries-old shipwrecks, as well as downed aircraft from the second world war.

Now the site has become central to another battle, by conservationists and campaigners, to safeguard Britain’s seas from damaging activities and to hold the government to account on its “30 x 30” pledge to protect 30% of marine habitats by 2030.

Goodwin Sands was awarded marine protected area (MPA) status by the government last year due to its biodiversity and unique habitats. But despite its status and fervent opposition by local conservationists, archeologists and historians, millions of tonnes of sand and gravel are about to be dredged from the site, as part of plans to extend the port of Dover.

Conservationists, who failed in a legal bid last year against the Marine Management Organisation’s decision to grant Dover Harbour Board (DHB) a dredging licence for the site, say the impending extraction is further evidence that MPAs are “useless” and fail to protect Britain’s seas.

Earlier this month the Guardian revealed that bottom trawling and dredging, the most destructive type of fishing on sea floor habitats, were happening in 71 out of 73 UK offshore MPAs, making a mockery of their “protected” status.

Goodwin Sands Conservation Trust is now lobbying the government to award the area greater protection, so that further dredging will not happen. It is backed by the Tory MP for Dover, Natalie Elphicke, as well as Dover district council.

Joanna Thomson, the trust’s chair, said: “This is an iconic piece of our maritime history and an important ecological site. What’s the point of an MPA if it offers no protection from dredging? There needs to be greater protections for our marine sites.”

The Marine Management Organisation (MMO) said that the area’s protected status was considered in the dredging application, and that significant environmental impact was “unlikely” if several mitigation measures included in the licence are followed. Other conditions include exclusion zones and the requirement to have an on-board archaeologist who will be responsible for checking material dredged.

But conservationists are adamant there should be no dredging within an MPA at all. Melissa Moore, of Oceana, said: “The MMO have failed to protect the habitats of the marine protected area. We need a clear government policy that all damaging activities will be swiftly halted in MPAs if we are to reach 30 x 30 targets.”

Jean-Luc Solandt, specialist in MPAs at the Marine Conservation Society, said: “The MMO contends that such dredging won’t have a significant effect. Yet it will take larval fish, it will kill sand eels. It will take some fauna living on and in the sediment. Shrimps, worms and echinoderms will be damaged and killed. This will upset the food chain. What are our MPAs for if such aggregate extraction, fish trawling and dredging is permitted within them? They are predominantly useless.“

Elphicke said that while little can be done to prevent the current dredging licence, she has pressed the government to give “marine blue belts” greater long-term protection in law.

She said: “The Goodwin Sands are a special part of our environment and should be afforded greater recognition and protection.”

Elphicke wants the sands to become one of five pilot highly protected marine areas where dredging and other damaging activities are banned, as recommended in a review published in June. The government has not yet responded to the review, which acknowledged that MPAs, in their current form, do not not give the protection necessary to allow marine ecology to recover.

The harbour board has said that 51 conditions attached to the dredging licence will protect the site’s environment, archaeology, war graves and the wider historic environment. But not everyone is convinced.

Dan Pascoe, a maritime archeologist, diver and the licensee of two of the area’s’ six wreck sites protected by Historic England, said that the shifting sands were constantly covering and uncovering their secrets. The Rooswijk, a Dutch East India ship that foundered in 1740 with the loss of almost 250 lives and now lies nearby, was once under 10 metres of sand. Seven years ago a Dornier bomber, shot down during the battle of Britain, was lifted out of the Goodwins almost intact.

“Shipwrecks are covered up and uncovered by the constantly shifting sands,” said Pascoe. “Who knows what else they could find down there? Dredging is quite a brutal extraction process, they suck and suck and only stop if something is jammed. Wooden structures get turned into matchsticks.”

A spokesperson for the MMO said that the dredging licence was the subject of three public consultations and it “remains satisfied” that its decision complies with relevant policies. The spokesperson said: “We understand the strength of feeling surrounding this development, both for and against. As a regulator that has to balance and manage competing uses of the marine environment, we accept that not everyone will be happy with the decisions we make.”

The owner of the Sands is the Crown Estate, which now stands to gain from the extraction. Asked why it had not objected to the dredging plans, given its previous opposition to wind farms on the grounds of risk to maritime archeology and the possibility of disturbing human remains, a spokesman replied: “Offshore wind development and aggregate extraction have very different implications for the seabed, with offshore wind requiring a much larger area (100 sq kilometres or more) and deeper foundations.”

The spokesperson refused to disclose how much the Crown Estate would benefit from the extraction: “This agreement is commercial in confidence. We are tasked with generating profit for the Treasury for the benefit of the nation’s finances.”