The year 2020 was meant to be a super year for nature and biodiversity, according to the UN. But with swathes of the planet in lockdown, Covid-19 has highlighted the risk of humanity’s unstable relationship with nature, with repeated warnings linking the pandemic with the destruction of ecosystems and species.

On Wednesday, the world will gather to discuss the biodiversity crisis at a virtual summit in New York. The UN secretary general, Antonio Guterres, Prince Charles and the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, will open proceedings. Here is what to look out for.

Will China step up?

Next year China will for the first time host major international talks on the environment – postponed from this year – at Cop15 in Kunming, where the international community will agree a Paris-style agreement for nature. The stakes are high: governments failed to meet any of the UN targets to slow biodiversity loss for the previous decade and the drum beat of warnings about the state of the planet’s health is growing louder. Now the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter is tasked with using its growing might to corral 196 countries into agreeing a plan worthy of the crisis.

Q&AWhat is biodiversity and why does it matter?Show

Biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth, in all its forms and all its interactions. “Without biodiversity, there is no future for humanity,” says Prof David Macdonald, at Oxford University. It is comprised of several levels, starting with genes, then individual species, then communities of creatures and finally entire ecosystems, such as forests or coral reefs, where life interplays with the physical environment.

Without plants there would be no oxygen and without bees to pollinate there would be no fruit or nuts. The services provided by ecosystems are estimated to be worth trillions of dollars – double the world’s GDP. Biodiversity loss in Europe alone is estimated to cost the continent about 3% of its GDP, or EUR450m (GBP400m) a year.

The extinction rate of species is now thought to be about 1,000 times higher than before humans dominated the planet, which may be even faster than the losses after a giant meteorite wiped out the dinosaurs 65m years ago. The sixth mass extinction in geological history has already begun, according to some scientists, with billions of individual populations being lost. Researchers call the massive loss of wildlife a “biological annihilation”.

Changes to the climate are reversible, even if that takes centuries or millennia, and conservation efforts can work. But once species become extinct, there is no going back.

China’s modern record on the environment is poor. Rapid economic development and huge infrastructure projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative have come at a huge cost to nature, destroying precarious ecosystems and leaving many cities with severe air pollution. But Beijing is uniquely placed to influence countries eager to follow its development model but distrustful of the conservation-focus approach of some European nations whose wild areas largely disappeared with industrialisation.

“I think China is absolutely critical to the issue of both climate change and biodiversity and land degradation. We are not going to solve these problems without leadership from China,” says Sir Robert Watson, former chair of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), which informs the UN biodiversity negotiations with the latest science.

Some privately suspect that President Xi will surprise world leaders with another major environmental commitment during his speech at the summit’s opening, just days after he ramped up China’s carbon commitments by pledging to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

“They’ve had some really bad examples of land degradation when they deforested the Yangtze basin. Now, as I understand it, they’ve done a fairly significant replanting of trees in the Yangtze basin because it was leading to extreme floods and dust bowls. They also, of course, have terrible air pollution in their cities. I’m somewhat optimistic that China wants to show it is an economic power and play a leadership role in the world,” Watson says.

“I would argue that governments around the world need to work closely with China and see if, collectively, we can move in the right direction.”

The absentees

Summit organisers have been overwhelmed with requests from world leaders to speak on Wednesday. The Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan, South African prime minister Cyril Ramaphosa and Britain’s prime minister, Boris Johnson, are among dozens of leaders jostling to make statements at the oversubscribed event. But the talks will be marked by those who are not scheduled to speak.

The US president, Donald Trump, and Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, will not appear, and while nobody from the US government is scheduled to address the event, Brazilian foreign minister Ernesto Araujo – who has previously dismissed the climate crisis as a Marxist plot – will represent his country. Both Trump and Bolsonaro oversee vital life-sustaining ecosystems with global significance and Brazil has traditionally been a major player in UN environmental circles through its impressive diplomatic machine.

But under Bolsonaro, the Amazon rainforest continues to burn and many fear Brazil’s leader is steering his country towards environmental ruin. Last week the president hit back at the UN general assembly for a second year in a row about how the Amazon has been treated under his leadership, claiming Brazil was the target of a “brutal disinformation campaign”. While the US is not a party to the UN convention on biodiversity, Bolsonaro’s stance on the environment could have a major sway over the final Kunming agreement. Governments will listen to what Araujo has to say with great interest.

One to watch

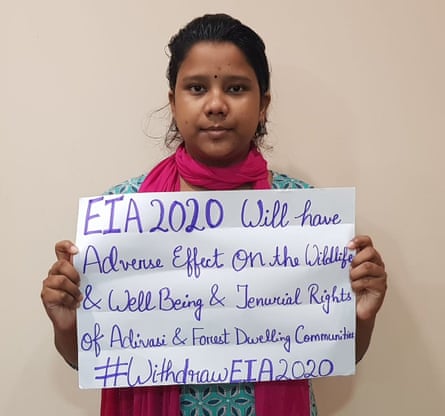

In between the world leaders, heads of state and royalty, indigenous youth activist Archana Soreng will also speak at the summit’s opening. The member of the Khadia tribe in India is part of the UN secretary general’s youth advisory group on climate change and will be a powerful voice for her generation.

Ambition to protect the planet

Before the coronavirus pandemic disrupted talks, Wednesday’s summit was meant to be the moment international leaders gave their input before negotiators headed to Kunming to thrash out a final agreement. While there is a danger that governments might ignore the environmental targets while grappling to rescue economies and save lives, there is cautious optimism that the opposite has happened. Repeated warnings linking Covid-19 and zoonotic diseases to the destruction of nature have focused minds.

“Look at the number of governments and states which have registered to make statements. That clearly by itself says something,” the UN’s biodiversity head, Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, told the Guardian. “Noticeable trends have emerged in this period of pandemic and in lockdowns. It has really brought up the voices of many actors we probably would not have seen or noticed.”

Despite the optimism, the ambition of the “Paris agreement for nature” will be reflected in the detail of measurable, targeted actions. As things stand, the draft Kunming agreement has headline targets of protecting 30% of the world’s land and sea by 2030, introducing controls on invasive species and reducing pollution from plastic waste and excess nutrients. Ahead of Wednesday’s summit, 64 leaders and the EU published an ambitious 10-point pledge that many privately hope will bounce other countries into being more ambitious. Watch out for how that translates into statements by countries such as Australia, China and India that did not sign the pledge.

Giving nature a financial value

Expressing nature’s value in financial terms has become a big focus of conservation efforts. With the cost of deforestation, pollution and species extinction absent from most economic models, calculating the economic contribution of ecosystem services that healthy forests, rivers and oceans provide to humanity has helped reframe the conservation debate.

Ahead of the talks, the insurance company Swiss Re calculated that more than half (55%) of global GDP, equal to $41.7tn, is dependent on high-functioning biodiversity and ecosystem services. But the research also found that major economies in south-east Asia, Europe and the US are exposed to ecosystem decline. The EU, Germany, Norway, Costa Rica and the UK are leading efforts to increase funding for nature. But to take meaningful action on the environment, many developing nations with high biodiversity – including Brazil and a number of African countries – want the creation of a global financial system that recognises their ecosystem services.

The UN’s co-chair on the Kunming process, Basile van Havre, who is tasked with combining all of the negotiating positions into a final agreement, said he understood their position.

“I think they’re putting on the table some concerns that need to be heard. There are commodities leaving Brazil and going to other places in the world, and they’re feeding economies in the other places. So, if I buy food items in the supermarket, how do we flow the money back to Brazil to support conservation? I totally understand the need of those local communities.”

While these issues will be sorted in the midnight negotiating hours in Kunming next year, watch for world leaders laying out their countries’ positions on ecosystem services on Wednesday.

The private sector and vested interests

Alongside governments, banks and private companies have announced commitments to protect nature ahead of Wednesday’s summit. HSBC, Allianz and Axa are among 26 financial institutions – representing more than EUR3tn in assets – calling on world leaders to reach an agreement to protect ecosystem function. Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest investor, will also take part in the leaders’ dialogue on harnessing science, technology and innovation for biodiversity.

But like the fossil fuel industry with climate talks, there could be significant pushback from major chemical and agricultural companies that might lose out through restrictions on fertiliser, farming practices and pollution through any agreement. Half a billion dollars of environmentally harmful government subsidies was highlighted as a key failure in the UN report on biodiversity targets.

“The landscape in the private sector is a bit different on nature and that’s one advantage we have,” Van Havre notes. “All that system of agri-food is very active and very worried because their bottom line depends on effective natural systems. They’re very engaged. They’ve learned from their climate change experience. So we’re not dragging them, they’re dragging us.

“It’s a very different world from the energy sector. We’re going to need to feed more people. So if anything, they have a bigger place in the world, it’s just a very different place.”

The summit as a focal point for campaigners

Ahead of the meeting, conservation groups and organisations have fired off a slew of press releases about biodiversity and their campaigning goals. Business leaders and philanthropists have announced increased funding for the preservation of nature alongside foreign ministers. The Wildlife Trusts has launched a GBP30m fundraising appeal alongside the UK’s new commitment to protect 30% of land and sea by 2030. Most events have been based around the four-day Nature for Life events, with discussions on the sustainable development goals, business and nature, global ambition and local action.

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features