In November 1966, the Gemini 12 spacecraft, carrying two astronauts, splashed down in the Pacific. The four-day mission was a triumph, proving that humans could work in outer space, and even step into the great unknown, albeit tethered to their spacecraft. It catapulted the US ahead of the USSR in the space race.

From then, Nasa’s goal was to beat the Russians to the moon. That meant weeks rather than days in space, in an isolated, claustrophobic environment. There was one perfect way to prepare humans for these conditions: going underwater. The world was gripped. If we could land people on the moon, why not colonise the ocean as well?

Nasa scientists were not the first to dream of marine living. Evidence of submarines and diving bells can be found as far back as the 16th century. The literary grandfather of all things deep, Jules Verne, popularised the idea of a more sophisticated underwater life with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in 1872, but it was in the 20th century that the fascination really took hold.

In the 1930s, American naturalist William Beebe and engineer Otis Barton collaborated on experimental submersibles called bathyspheres which set records for deep diving and opened up the underwater realm of plants and animals to science. Swiss physicist and oceanographer Auguste Piccard created the bathyscaphe (which used floats rather than surface cables) in 1946, and his son, Jacques, was on the record-breaking voyage to explore the Mariana Trench, the deepest place on Earth, in 1960. Auguste also created the mesoscaphe – the world’s first passenger submarine – in 1964.

The craze for living in the depths, rather than merely visiting, started in the 1960s, when Jacques-Yves Cousteau – inventor of scuba, wearer of red woolly hats and inspiration for ze French Narrator in Spongebob – brought the ocean vividly to life for millions around the world through his documentaries about life aboard his vessel Calypso.

To Cousteau, the life subaquatic was, above all, for living. “Being French, he made sure his diving never got in the way of mealtimes,” writes author John Crace of Cousteau’s documentaries. “In fact, food and wine take almost equal precedence with the oceans in these films. No one is ever without a pipe or cigarette in their mouth, either. Except underwater, of course.”

Cousteau channelled this vision of oceanic life into his underwater habitats, known as Conshelf (Continental Shelf Station). George F Bond, the father of saturation diving and head of the US navy’s Man-in-the-Sea programme, approached Cousteau with funding from the French oil industry: they wanted manned colonies at sea in order to help with future exploration.

Together, Bond and Cousteau built three Conshelfs. The first, in 1962, was suspended 10 metres under the water off the coast of Marseilles, but Conshelf II was a starfish-shaped “underwater village” that sat on the seabed proper, 30 metres down in the Red Sea off Sudan. It contained all the accoutrements of la vie louche, including television and radio. Cousteau used it as a base to explore the ocean in his yellow submarine, descending to 300 metres to capture the deepest footage yet recorded.

His team spent 30 days beneath the waves, and in the process changed humanity’s relationship with the ocean by proving that “saturation diving” could allow people to spend long periods underwater. By diving to a certain depth, divers saturate their bodies with the inert gases in air. This allows them to exist at the extreme pressure of the ocean floor. It typically involves breathing a mix of helium and oxygen, to avoid the possibility of the bends and nitrogen narcosis.

Conshelf sparked a craze. Sealab, Hydrolab, Edalhab, Helgoland, Galathee, Aquabulle, Hippocampe – more than 60 underwater habitats were dotted across the seabeds in the late 60s and early 70s from the Baltic to the Gulf of Mexico.

The craze even inspired two British teenagers, Colin Irwin and John Heath, to raise GBP1,000 to build Glaucus in 1965, which was little more than a cylindrical steel tank weighed down by old railway ties. “We all thought at the time, ‘This is the future’,” Irwin told the BBC on Glaucus’s 50th anniversary. “We may not populate the moon, but we’re going to have villages all over the continental shelf, and we thought it’s about time the British did the same thing.” They dropped it in the waters of Plymouth Sound and spent a week inside.

It is the Nasa missions, however, that remain the most iconic of the 60s underwater living experiments. This is in large part due to the marine biologist Sylvia Earle, one of the most famous explorers of her generation. In 1969, Earle made history with Mission 6, when she and an all-female team of scientists spent two weeks on Nasa’s habitat Tektite (named after meteor remnants on the seabed). This Virgin Islands research facility was for studying aquatic life – marine science, engineering and construction underwater – and small-crew psychology in extreme conditions. The research was for the Apollo missions and the moon landing was just months away.

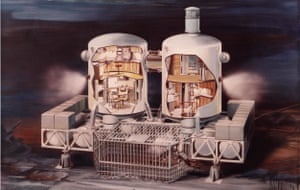

Built by General Electric, Earle and her team would enter Tektite through what she calls an “underwater door” – emerging as if from a swimming pool into the deep-sea two-up, two-down apartment. It was dry, climate-controlled and comfortable, with carpets, bunks and a hot freshwater shower to wash off the salt. It even had a microwave.

“Nasa had a team of psychologists watching to get insight into behaviour of living in isolation,” says Earle today. “We were there as guinea pigs: our research was on the oceans, their research was on us.”

But Tektite wasn’t just a research station – it was a vision of stylish underwater living. With their scientific gear and Charlie’s Angels wetsuits in their Bond-villain lair, Earle and her team caused a media sensation.

“They called us the aquababes, the aquanaughties, all sorts of things,” Earle recalls with a snort. “We speculated what they would say about the astronauts if they were seen the same way – would they be the astrohunks?”

Habitats such as Glaucus, Conshelf and Tektite were built as tributes to humankind’s abilities, but their true achievement was to spark an entirely different understanding of marine animals. “Back then we could only explore using nets, and just saw dead bodies – not living creatures. Having the continuous interaction allowed us to get to know individual animals,” Earle says. “[In underwater habitats] we could stay, the way you look at bears or birds: we were there for the long haul, 24 hours a day or night. It was possible to see how a little group of damselfish reacted when a predator tried to swipe their eggs, for example.

“You look at a school of fish and they all look alike, but when you really look at them – well, it’s like a bunch of people getting on the New York subway: a fish would say they all look the same, but we know they’re different. Getting to appreciate the individuality of creatures other than humans was a breakthrough for me – it reinforces that you can’t just lump them all together.”

But, in 1973, the world was shaken when Opec declared an oil embargo. Energy prices in the west skyrocketed. At first, the oil shock fuelled even wilder fantasies of a watery future, straight out of science fiction. Architects and designers imagined whole cities underwater, fed by hydropower stations, with deep-sea mining using freight submarines.

Much like living in space, though, it’s extremely difficult to live underwater. Aquanauts spending months in saturation suffered intense pressures on their body tissues – their brains, nervous systems. There were also interpersonal problems. As the marine biologist Helen Scales notes in her 2014 radio documentary The Life Sub-Aquatic:”If you’ve ever lived in a house with anyone, the first thing you do is storm out if you have a quarrel. You’re not going to do that [underwater].”

Advances in robotics changed the game. Much of the research being done by Earle and her colleagues could be more efficiently performed by humans operating devices remotely from the surface. By the end of the 70s, the US government pulled back on its efforts. The moon missions were over. So, it seemed, were the ocean habitats.

A few people refused to let the dream die. One was Australian Lloyd Godson. His habitat, BioSub, experimented with sustainability. Fuelled by solar panels, it featured a support system adapted from work by American high school students, with algae removing the CO2 from his exhalations and creating oxygen. In 2007 he moved in. It worked – sort of. “By day 12 I was lethargic, getting really irritated with people asking questions,” he told the BBC. “My wife told me to call it a day.”

In 2010 Godson spent 14 days underwater at the Legoland aquarium in Germany and used a fixed bicycle to set a world record for generating electricity underwater.

Better funded is the French architect Jacques Rougerie, who has built a career designing underwater habitats and environments. “I had the pleasure of going on Cousteau’s Calypso, participating in expeditions, talking to the crew – and what he created was a fascination for underwater living,” Rougerie says from his office in Paris. “The early explorers opened the chamber of the possible for humanity. When you are underwater you feel like you’re in a new dimension – floating in space, like an astronaut.”

Citing Leonardo da Vinci as an inspiration, Rougerie designs sea museums, underwater laboratories and habitats, and his foundation hosts an annual competition for students to conceive of underwater villages. Rougerie himself has twice lived for long periods underwater, and both times he didn’t want to return to land. “Sadness invades you,” he says. “I was happy to come back and see family, but the first thing you think of is the next experience.”

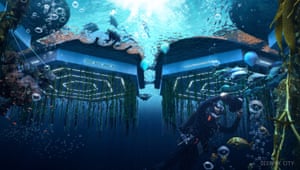

Rougerie’s ultimate goal remains that old 1960s dream: a proper underwater village, housing up to 250 people. In his vision, these aquanaut settlers would live in osmosis with the ocean, in a self-sufficient, autonomous community running on renewable marine energy such as tidal power, wave sensors and ocean thermals.

Perhaps most ambitious of all is SeaOrbiter, Rougerie’s take on the International Space Station for the ocean. It looks like a floating seahorse: two-thirds of its 51 metres are submerged, with panoramic windows, the lower section acting to stabilise a huge sail-shaped portion above water.

“The goal, above all, is to help the climate and biodiversity by exploring across the grand currents of the ocean,” he says. “To float 24/7 on a permanent structure, a combination of men and robots with a scientific purpose.”

Despite Rougerie’s claims that he has secured Chinese investment, SeaOrbiter appears no closer to pushing off.

Indeed, after all the projects of the past 50 years, only one permanent underwater habitat remains on the entire planet: Aquarius Reef Base, a research station run by Florida International University and which sits 20 metres down on the seabed off the Florida Keys.

Aquarius plays host to a stream of people – scientists, film-makers, astronauts, even Jacques Cousteau’s grandson Fabien – who want to experience time underwater. As part of Nasa’s Extreme Environment Mission Operations (Neemo), the Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, famous for singing David Bowie songs aboard the International Space Station in 2013, used Aquarius to train.

But Aquarius is still just a small research station, with room for just six people. In the 21st century, underwater “living” has become almost exclusively the preserve of hotels and resorts that sell “experiences” to guests via underwater glass ceilings and fish windows. The world’s largest underwater restaurant opened in Norway in 2019. Submerged hotels in the Maldives, Fiji, Dubai and Singapore use elevators to take guests below the waterline, and feature amenities such as Poseidon’s undersea chapel (“for a wedding ceremony or vow renewal truly unlike any other”), and are a lot more comfortable than Tektite ever was.

Instead, the architects and scientists who still look to aquatic habitation spend most of their time thinking not about underwater cities, but floating ones. Long the refuge of the poorest city dwellers, such as the vast Makoko floating slum of homes on stilts in Lagos, houses on water have become newly popular as waterfront property prices – and sea levels – have risen across the world.

So far, most of this effort to colonise the water has gone into land reclamation projects, such as the Odaiba island in Tokyo, or South Korea’s Songdo “smart city”. Architects in Dubai even tried to create a scale model of the entire Earth off its coast. However, reclamation is expensive, and requires constant maintenance to keep the ocean from reclaiming the space. Japan’s Kansai airport is sinking.

Architect Koen Olthuis thinks it’s more natural for cities to spread by floating. His firm Waterstudio builds floating buildings, mainly in the Netherlands, to help cities be more resilient. Recently, Olthuis started adding submerged levels to his structures. “In Holland the licences for dwellings on the water are small, but they say nothing about living underwater.”

The goal is partly ecological, Olthuis says. “Ten years ago, it was about proving that a structure did not have a negative effect – but now it’s about also having a positive effect.” He points to the “rigs to reefs” principle where abandoned oil rigs have been transformed into habitats for ocean life. Waterstudio’s Sea Treebuilds on that concept: it’s a platform that attracts birds, bees, fish and water plants into a single dense floating structure that can be moved between cities. He says the first Sea Trees have been commissioned by a Chinese developer in Kunming, who was asked to create a tourist attraction after a dam permanently altered the landscape.

The Bjarke Ingels Group last year revealed a concept for a buoyant municipality called Oceanix City – a modular system of floating islands clustered in multiples of six to form a kind of archipelago. Meanwhile, the Seasteading Institute, founded by PayPal’s Peter Thiel and the grandson of the economist Milton Friedman, continues to pursue its libertarian goal of floating communities living outside the boundaries of national law. The Chinese construction giant CCCC has a design similar to Oceanix City, while the architect Vincent Callebaut has imagined a city called Lilypad with a series of oceanic skyscrapers that would house 50,000 people.

“I see blue cities,” says Olthuis. “Not floating cities. Just a city growing over water, taking advantage of the floating structures but in the same pattern as on land – a kind of Venice but floating, that can be used in New York, Miami … any city that’s threatened by water.”

The craze for deep-sea living wasn’t entirely folly, though. Rougerie says that time beneath the waves changes our outlook on the planet, helping inspire the environmental movement. It’s why continues to sponsor the competition to design underwater cities. “The biggest threat to our ocean is man: pollution, chemical and plastic. But I’m convinced that the young have a conscience and they’ll do everything in their power – they’re totally committed and willing to find a solution.”

Sylvia Earle, too, believes that man’s understanding of the universe has been changed by underwater exploration. “In the last 50 years,” she says, “two major things have happened: the expansion of our technology into the skies above – which has given us great insights into the blue speck in the universe that we couldn’t understand any other way – and going deep in the ocean, which has also changed everything.

“It has taught us that life exists everywhere, even in the greatest depths; that most of life is in the oceans; and that oceans govern climate. Perhaps because we’re so terrestrially biased, air-breathing creatures that we are, it has taken us until now to realise that everything we care about is anchored in the ocean.

“It’s the ocean that drives planetary systems – and we have done more harm to our life-support system in the last 50 years than we have in all previous human history,” she says. “If we fail the ocean, nothing else matters.”